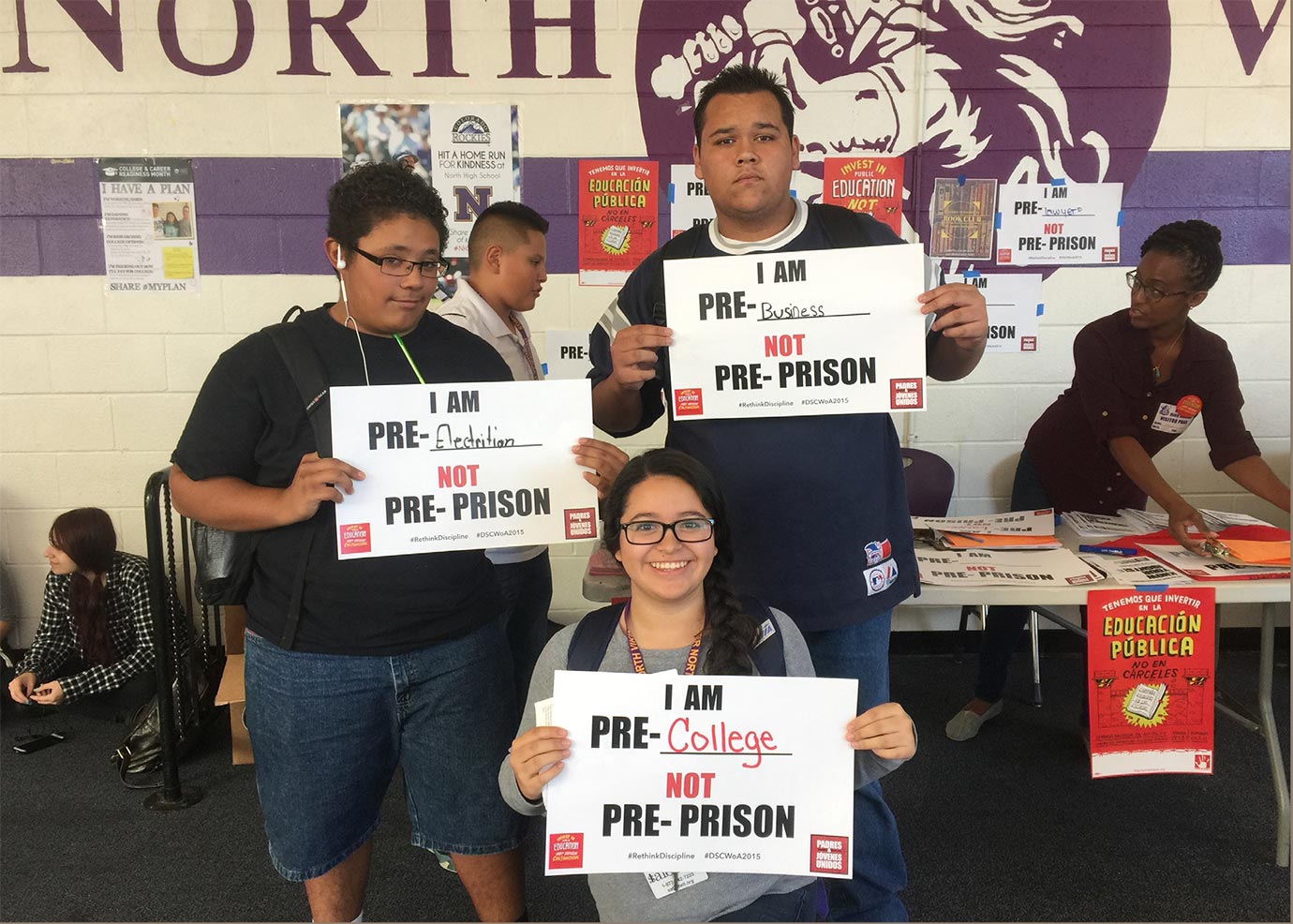

Youth members at North High School in Denver take a stand against the school-to-prison pipeline during the Dignity in Schools 2015 Week of Action. Photo via Padres & Jóvenes Unidos

Youth members at North High School in Denver take a stand against the school-to-prison pipeline during the Dignity in Schools 2015 Week of Action. Photo via Padres & Jóvenes Unidos

Over the past couple of years, local, state and national teachers’ unions have undergone what one local union leader in Colorado calls “a sea change” in their attitudes toward student discipline issues and how teachers should approach them.

In the past, unions advocated for the right of teachers to remove disruptive students from their classrooms, and focused less on the impact this might have on those students.

The National Education Association’s (NEA) focus was making sure that schools were “safe, happy, productive places,” said Kerrie Dallman, president of the Colorado Education Association (CEA), the NEA’s state affiliate.

Now, however, Dallman said, there’s a new focus: the realities of institutional racism on discipline practices, and the impact that has on students of color.

Working with the advocacy group Padres & Jóvenes Unidos, a Colorado Trust grantee, CEA has supported pilot restorative practices in Denver schools. (Schools elsewhere in Colorado are also using a similar approach.) The goal, Dallman said, is to narrow the school-to-prison pipeline that developed from harsh zero-tolerance discipline policies that were in vogue for much of the past 20 years.

Zero-tolerance policies can criminalize student misbehavior, particularly in schools that have a full-time police presence. Under zero-tolerance, students have faced long suspensions and even arrest for relatively minor infractions. This could lead to a cascading series of crises, leaving students out of school and steering toward prison gates. Research by Padres & Jóvenes Unidos has found such practices in Colorado disproportionately impact students of color.

Daniel Kim, director of youth organizing at Padres & Jóvenes Unidos, said union support for less draconian discipline policies is a potential game-changer.

“In the past, the default position of unions has been to protect the discretion of teachers on discipline issues, which is understandable to an extent,” Kim said. “But… when practices are harmful to kids, that is not OK.”

Last May, the NEA issued a policy statement on “discipline and the school-to-prison pipeline.” The 60-page document pledged to launch an education campaign about “problems and disparities in school discipline” and to create model discipline policies with an emphasis on approaches such as restorative practices.

At about the same time, Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, the other major national union, offered a mea culpa in a letter published in the AFT’s member magazine.

“Many people have called for reevaluating so-called zero-tolerance policies,” Weingarten wrote. “These policies were promoted by people, including me, who had hoped they would standardize discipline procedures and free students from the disruptions of misbehaving peers; it was analogous to the broken windows theory of policing. We were wrong.”

Dallman recalled a couple of incidents from her high school teaching days in Jefferson County, when zero-tolerance was the norm. Students were suspended for acting out when, in hindsight, more moderate measures would have served everyone better.

“I didn’t have the skills to deal with complex behavioral issues,” Dallman said. Many teachers still lack those skills today, she added: “My experiences have cemented my desire to help teachers focus on gaining more skills to deal with these issues, and to help get students the skills they need to cope with their emotions productively.”

School discipline issues often have their roots in health issues, Dallman said. “A lot of kids who act out are doing so as a result of something else going on in their lives.”

If schools had the resources to better address students’ social and emotional health, “we’d see a decrease in suspensions and expulsions,” Dallman said.

Related stories: