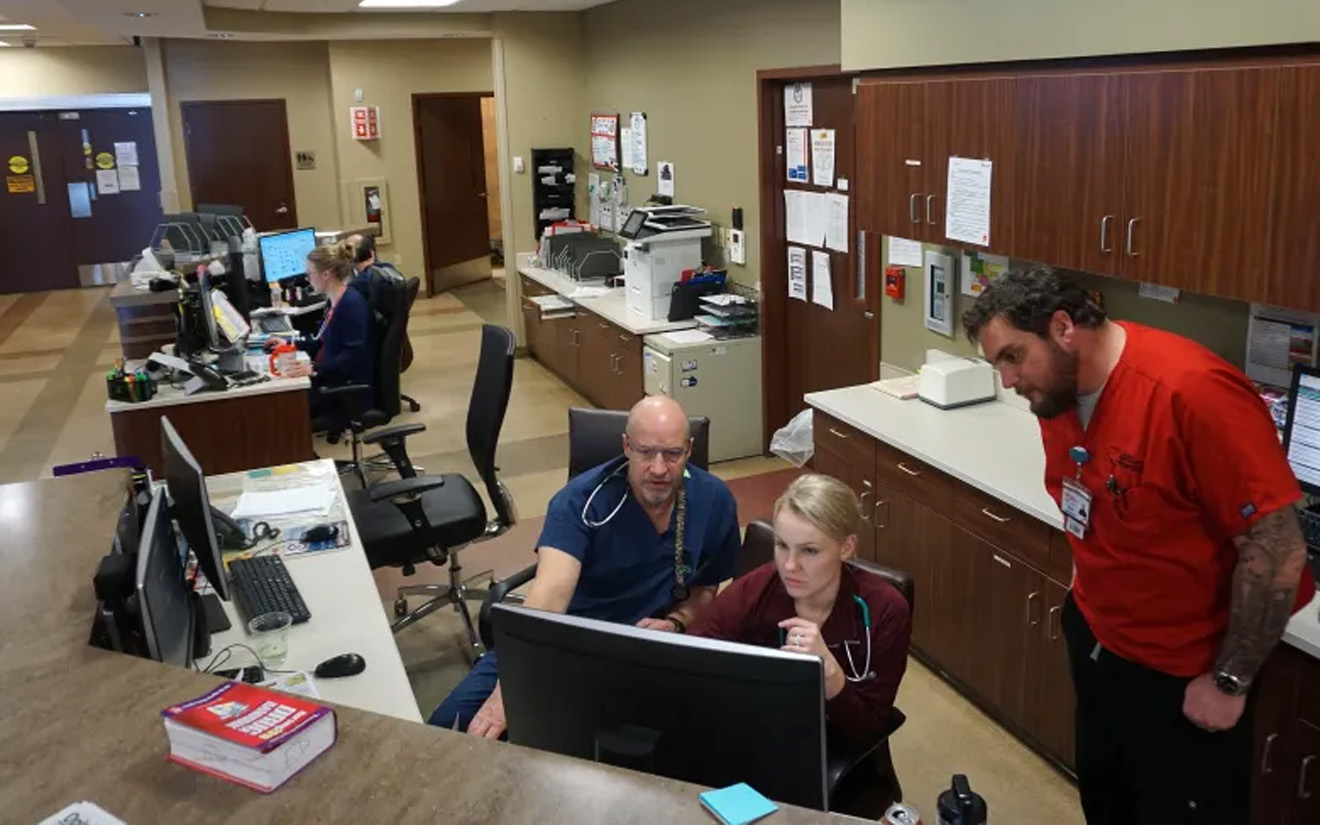

Nursing student Nathan Allred, right, works in the Memorial Regional Health emergency department with nurses Jacie Jourgensen and Dave Higgins on Feb. 27, 2020. Photo by Matt Stensland / Special to The Colorado Sun (used with permission)

Nursing student Nathan Allred, right, works in the Memorial Regional Health emergency department with nurses Jacie Jourgensen and Dave Higgins on Feb. 27, 2020. Photo by Matt Stensland / Special to The Colorado Sun (used with permission)

On a typical spring day, Craig’s Memorial Regional Hospital, in the rural northwest part of Colorado, monitors patients in 10 of its 25 available beds. As of March 25, there were no confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Moffat County, a four-hour drive from Denver.

But the pandemic is already having a disastrous effect on Memorial.

Pleas by the state to avoid nonessential surgeries and procedures, combined with residents’ worries about infection, have cut the Craig patient census to six a day. Craig Memorial can’t survive long on a 40% drop in its biggest source of revenue.

In Teller County at the western foot of Pikes Peak, the senior services agency, Teller Senior Coalition, which had just acquired a third wheelchair van for rides, has switched to crisis scheduling: Medical rides only, and food deliveries to seniors too vulnerable to go shopping. And no two-passenger trips.

And in Hugo on the Eastern Plains, Lincoln Community Hospital has built an airlock and isolation unit between its inpatient beds and its long-term care facility. The hospital has no COVID-19 patients yet, but dozens of canceled surgeries, specialty rotations and primary care visits make the CEO wonder if they can keep the doors open in three to four months. He’s hoping that Front Range hospitals hit hard by the virus will transfer non-critical, non-COVID-19 patients an hour away to Hugo, for good care and a little shared revenue.

The combination of higher crisis-prep expenses and lower revenue has already prompted a warning to staff that hours might be reduced.

“We’ve very concerned about our long-term viability,” said Lincoln Community CEO Kevin Stansbury.

Without yet delivering patients they can help, COVID-19 has nevertheless delivered the prospect of financial ruin to many of the rural hospitals Colorado health officials say have been on the verge of closing for years.

“We’ve got 18 rural hospitals operating in the red right now, so any loss of revenue is going to be felt hard, and felt for a long time,” said Michelle Mills, CEO of the Colorado Rural Health Center, the nonprofit state office for rural health concerns. Hospital CEOs themselves say the number in trouble is likely more than 20.

Rural hospitals and federally qualified low-income clinics may get some relief from the forthcoming, record-setting $2 trillion federal stimulus package written to combat the drastic economic impacts of the pandemic across the country. Rural health leaders and industry associations lobbied through their state delegations to include both COVID-19 mitigation costs and simple cash infusions for rural facilities. They also requested a boost in Medicare and Medicaid payments for patients transferred from an urban facility to ease overflow.

Mills and others said this week it was unclear how the details would be written and how much would be sent to Colorado.

Colorado’s small-town facilities are taking extraordinary measures to be ready for a COVID-19 wave while also continuing vital care, Mills said. She knows of one facility that set aside rooms normally reserved for visiting specialty physicians to prepare for virus patients, and created a system where incoming ER patients would be triaged while still in their car in order to avoid new infections and overcrowding.

In Craig, the comprehensive societal change brought on by the pandemic means the hospital has to broaden its role as a social services hub, said CEO Andrew Daniels. Many providers and hospital staff have children whose lives have been upended by school closures. So the hospital created its own day care center to keep staffers coming to work.

Craig now has a no-visitors policy, and prepared a negative air pressure wing for future COVID-19 patients. It has a separate clinic office near the town’s Walmart, and has designated that “rapid care” center for minor problems to keep operations flowing at the main hospital. The hospital has what it believes to be adequate stores of protective equipment and ventilators, and is part of the network offering to take on Front Range overflow patients.

Preparation is not the problem.

“As people are fearful, they are canceling their doctor’s appointments, canceling their surgeries, canceling their procedures,” Daniels said. “As we see volumes drop off, this hospital was struggling financially anyway. So the real worry is what’s our long-term viability if this thing continues.”

Teller County is ready to transport any seniors for medical appointments at the hospital in Woodland Park, but for now has seen more requests for delivered food and prescriptions. So Teller Senior Coalition sends out its three van drivers to pick up orders and leave them on the front steps of homes, said Executive Director Katherine Lowry.

“We delivered 30 bags today, and we’ll deliver more than that tomorrow,” Lowry said. The vans formerly offered rides to the senior center and other locations, but during the crisis trips are now limited to medical and food purposes, Lowry said.

“I was just on the phone with a senior who is afraid to go out shopping, so we’re going to deliver food to her tomorrow. And there are women with cats who need pet food so their animals don’t starve,” Lowry said. “We’ve transitioned to be more of a food provider than we usually are, but that’s the need right now.”

The inequities between rural and urban resources and care extend to COVID-19 testing. Some metro hospital labs have developed their own capability for rapid results, which allows them to organize triage and inform public health officials about patterns. Rural hospitals can’t justify the expense of setting up their own testing, and are waiting over a week in some cases for results from cases they call presumptive COVID-19, said Lincoln Community Hospital’s Stansbury.

Lincoln Community Hospital does not have an ICU or ventilators, so the most serious patients would be transported to Front Range facilities. “We’ve canceled specialty services for a month, and that revenue has me greatly worried,” Stansbury said.

While some rural hospital districts take in special health taxes, many rely almost solely on patient revenue. Any that do have a taxing district are likely to see revenue declines there as well, as various shutdowns affect sales and property taxes.

For now, CEOs like Stansbury are not exactly hoping for virus patients, but they do hope that if Front Range hospitals need help, they can make up revenue as a “relief valve,” Stansbury said, adding: “We are pretty adept at doing more with less.”