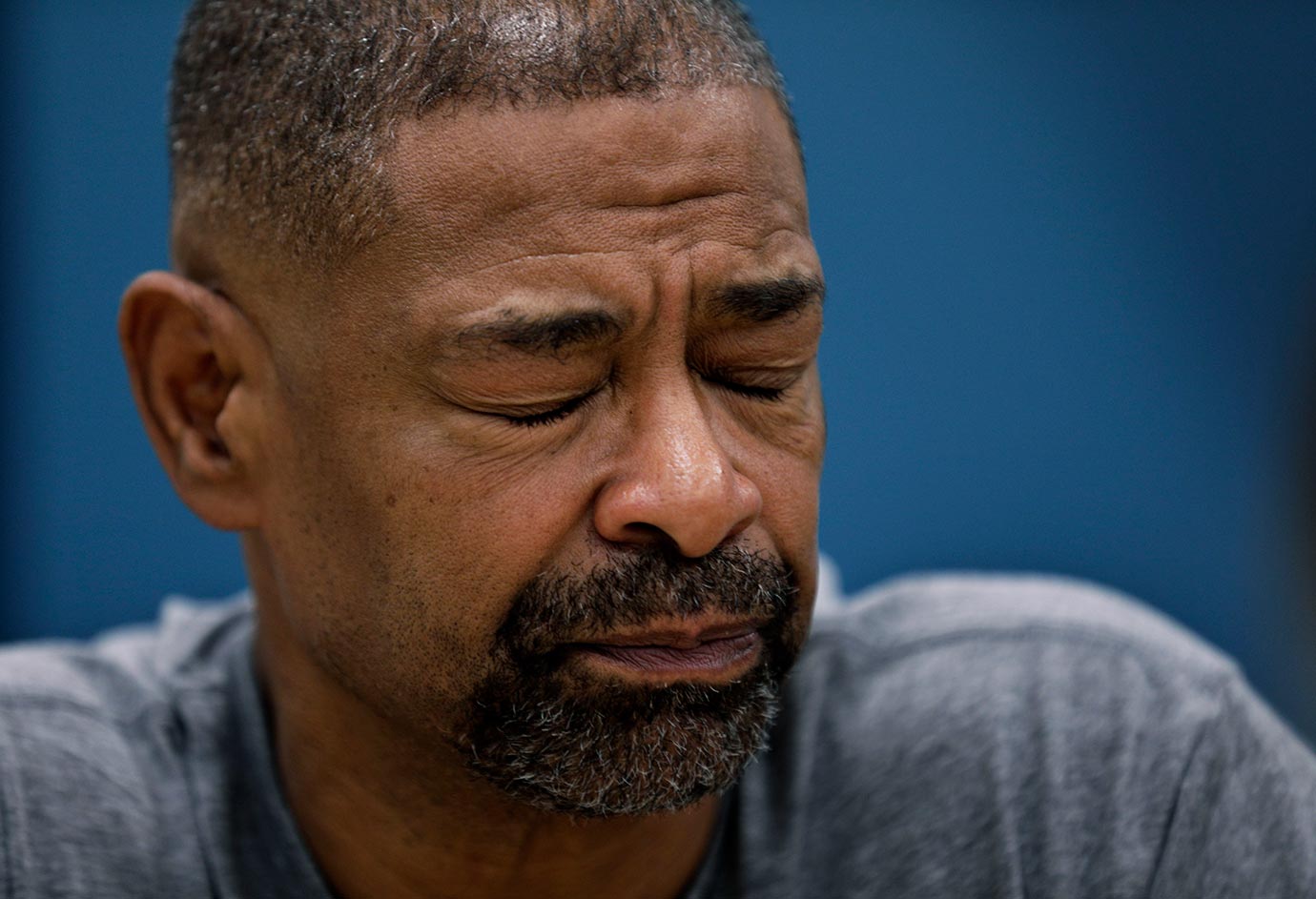

Sam Hawkins says he is “still sick emotionally” from his son’s 2005 murder in Denver. The case remains unsolved. Photo by Joe Mahoney / Special to The Colorado Trust

Sam Hawkins says he is “still sick emotionally” from his son’s 2005 murder in Denver. The case remains unsolved. Photo by Joe Mahoney / Special to The Colorado Trust

The numbers are staggering.

More than 300,000 homicides across the United States have gone unsolved since the 1960s, leaving families and communities traumatized and struggling to find justice that might never come. In Colorado, at least 2,500 murders have gone unpunished in the last five decades.

Black Americans living in underserved areas are impacted in greater numbers than other populations by virtue of experiencing more murders and fewer arrests in their communities, according to a Washington Post analysis of homicides over the past decade in high-violence areas of major American cities, including Denver.

The historic Five Points community and adjacent areas northeast of downtown Denver, once a hub of the Black community, were singled out in the Post analysis as having the highest number of homicides and the fewest solved murders between 2010 and 2017. Twelve people were murdered in this neighborhood during that period; eight of the 12 were people of color. Nine of the cases were not solved.

For community leaders, the numbers represent lives destroyed, families torn apart and communities ravaged. Jeff Fard, the Five Points community organizer and activist known as Brother Jeff, said that the high volume of murders and unsolved murders “paralyzes a community with fear and distrust.”

“Anytime you have unsolved murders in a community, that’s going to tell you that murderers are walking around that community,” said Fard, founder and director of Brother Jeff’s Cultural Center. “It also tells you that families and communities do not have closure.”

Lack of closure, combined with the tragic loss of a loved one, complicates and delays the grieving process, often precipitating longer-term detrimental effects on those left behind, health experts say.

“Loss is bad enough. Traumatic loss is terrible. But ambiguous loss… is the sense that you can’t say goodbye,” said Sandra Bloom, MD, a Philadelphia psychiatrist and nationally recognized expert on violence and trauma. “You can’t let the loss go because the murder has not been solved.”

Such trauma and ambiguity can manifest itself in extreme anxiety along with physical and mental symptoms similar to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), Bloom said. These include eating and digestive problems, difficulty sleeping, frequent crying, heart palpitations and flashbacks that leave one dwelling on the past. The health impacts are similar regardless of race, she added.

“It’s not that Black people have any different response than white people do,” Bloom said. “It depends on your neighborhood.” For residents in high-violence neighborhoods, reminders of the tragedy may be frequent, triggering memories of “that loss on a continuing basis,” she said. In some places, “there are still blood stains, there are little flowers left… there may be body outlines—it’s awful.”

Children exposed to the adversity and trauma of an unsolved murder when their brains are still forming can develop ongoing stress, known as toxic stress, that can lead to significant health and developmental problems, said Bloom, an associate professor at Drexel University School of Public Health.

Who and Why?

After his only son was murdered near downtown Denver on Aug. 23, 2005, Sam Hawkins could not sleep, eat or muster the strength to go to work.

Samuel Cameron was gunned down in an alley near Bayaud Avenue and Pennsylvania Street, about two miles southeast of downtown Denver. Cameron was 25 years old and left behind a daughter and pregnant wife.

Nearly 14 years after the slaying, the killer has not been caught, leaving Hawkins and other family members distraught, and fiercely determined to find justice for Samuel. “He was my only kid,” said Hawkins, a security officer for Jefferson County Public Schools. “I’m still sick emotionally. It’s ongoing.”

Cameron was “smart, easygoing and had a big heart,” said Hawkins. “He talked about wanting to be a lawyer someday so he could help people.”

But Hawkins said his son “got involved with the wrong crowd and ended up in jail for having drugs.” That was about a year before the murder, which police suspected was gang-related.

Hawkins said his emotions are triggered by daily memories of his son, the knowledge that his grandchildren have no father, and constant despair over who took his son’s life and why. There is another trigger as well: anger. Hawkins can’t stop wondering if perhaps police gave his son’s case less attention because of his race.

“My kid was a young kid and a Black kid,” Hawkins said. “His being Black and possibly in a high-risk category, I don’t know if his case got the attention that police give to other cases.”

Family members of unresolved murder victims, like Hawkins, share not only the loss of loved ones but also frustration and anguish that the cases have gone unsolved after months or years, said criminologist N. Prabha Unnithan, PhD, a professor of sociology at Colorado State University.

Failing to solve homicide cases “violates our fundamental sense of trust, justice and fairness in our communities and our criminal justice systems,” he said.

Robert Wells, executive director of the Colorado advocacy group Families of Homicide Victims and Missing Persons (FOHVAMP), knows Hawkins and empathizes with him and all families seeking justice for an unsolved murder. FOHVAMP was formed in 2001 by victims’ families who believed police were not doing enough to resolve their loved ones’ cases.

“Grief turns to anger, rage and helplessness as time goes on and nothing happens,” said Wells. “Disappointment in our system of justice, in the very people we depend on to help us, grows.”

Wells has sought justice for his younger brother’s unsolved murder for more than 35 years. Sid Wells was murdered in his Boulder, Colo. condominium on Aug. 1, 1983. Another brother, Sam Wells, discovered Sid’s body in a pool of blood with a shotgun blast to the back of his head.

The case made headlines because the 22-year-old journalism student was dating the daughter of actor Robert Redford. A suspect, Sid’s roommate, was arrested, released and disappeared; the arrest affidavit indicated that cocaine might have been a factor in the killing. The murder went into a cold case file until 2010, when a new prosecutor revived it and filed a first-degree murder warrant for the same suspect’s arrest.

Rob Wells said the murder turned his family’s lives upside down. His father had been killed two years earlier in a car accident involving a drunk driver. His mother, who suffered from cancer, spent the years before she died working to keep her son’s unsolved murder case alive. Weeks after the murder, a still traumatized Sam Wells was behind the wheel of his car when a drunk driver plowed into it. He sustained a serious brain injury and was diagnosed with PTSD.

“I freaked out,” Sam Wells said of the moment he discovered his brother’s body. “It caused me to go into a severe depression. I tried to go to counseling, but it didn’t work.” He also tried to finish college and get a stable job, he said, but that didn’t work, either.

“I try to stop thinking about it… It just pops into my head,” Sam Wells said of that moment more than three decades ago. He now lives alone in a camper in Mead, Colo., which he said was purchased for him by his brother, Rob. “My brother helps me a lot.”

Rob Wells breaks down in tears when discussing the ordeal.

“Depression is a challenge at times,” he said. “My health has been an issue. If this had not happened, the majority of my daily life would not be consumed with the horrors that people inflict on one another, and I would not be crying as much as I do.”

Rob Wells said he has learned from interacting with families that regardless of race, ethnicity or neighborhood, the loved ones of unsolved murder victims “are not dealt with in an effective way.”

“They’re not being given all the information. They don’t know what’s going on. Police might not have any logical leads, but they’ll never tell you,” he said.

Sam Hawkins can vouch for that. Every year since his son was killed, Hawkins has called Denver police on his son’s birthday, on the anniversary of the death and one or two other times.

“I tell them I’m calling about my son’s case and it’s been X-amount of time since he was killed and I would appreciate a call-back as a courtesy,” Hawkins said. “I know they’re busy so I always make a point of asking them to call me back as a courtesy, even if they don’t have any new information.”

“Most of the time they don’t call him back,” added his wife Sharon Hawkins, Cameron’s stepmother.

Joe Montoya, division chief of investigations for the Denver Police Department, said that while homicide detectives “really care about the families,” there “probably won’t be constant contact… especially if there’s just nothing to move on” in terms of case developments.

“It’s probably not a bad idea to have someone in general to reach out to the families on occasion, just to let them know we haven’t forgotten about them,” Montoya said.

A “Cold Case Crisis”

Across the country, so many unsolved murders are accumulating—from wealthy Palm Beach, Ca., to modest Ovid, N.Y., and places in between—that some experts have expressed alarm.

Despite fewer homicides nationwide in recent decades, “police have had less success in maintaining clearance rates for homicides,” the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Assistance said in a recent report.

Every criminal homicide impacts surviving family members and untold numbers of friends—in other words, potentially millions of people have been left to cope with the endless uncertainty of who took their loved ones’ lives and why.

Jim Adcock, PhD, a former coroner and founder of the Mid-South Cold Case Initiative in Memphis, Tenn., believes “we’re in a cold case crisis.”

“If we don’t address it, the issue is just going to get worse,” Adcock said. “The cost of doing nothing is getting higher and the hole we’re in is getting deeper and deeper.”

The national “clearance rate” for homicides in 2017 was 61.6 percent, according to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), down from 90 percent in the 1960s. The clearance rate is FBI terminology for the percentage of cases that end with an arrest or by “exceptional means,” such as an identified offender has died or was not charged. Denver’s overall clearance rate of 64.4 percent in 2017 means that more than a third of homicides are going unsolved.

“Leaving more than 30 percent of homicides unsolved is unacceptable,” Adcock said. “We need to make (solving homicides) a national and local priority.”

Cameron’s 2005 murder was among 16 homicides in various parts of Denver that year for which no one has been held accountable. The Colorado Bureau of Investigations (CBI) cold case database shows more than 700 unsolved killings in Denver dating back to 1970.

In neighborhoods analyzed by The Washington Post in the nation’s 50 largest cities, the numbers were equally dismal. About half of the more than 50,000 homicides in the analysis were unsolved. And nearly three-quarters of the victims were Black.

Charles Wellford, PhD, a University of Maryland criminologist who for decades has studied homicide clearance rates, said research has not found a link between the race of a victim or offender and the amount of attention given a homicide case by law enforcement.

The reality is that many of the homicides that cluster in certain communities involve gang violence, drive-by shootings, stranger-on-stranger killings—“cases that are the most difficult to clear,” Wellford said.

Before gentrification took off, historic Five Points included the River North Art District, San Rafael Historic District and areas of the Curtis-Champa Streets Historic District—parts of which were outlined in the Washington Post analysis as areas where murder rates were high and arrests low. The Whittier neighborhood was also included. This geographic area is now largely white with a Hispanic population larger than the Black population. Pockets of the community are vulnerable to gang and drug activity.

Many experts agree that making an arrest can prevent a killer from committing additional homicides, and that failing to do so perpetuates the cycle of violence. Families blame apathetic police departments for failing to solve murders. Wells believes police prioritize cases based on the ease with which they think they can get a conviction.

Police point to inadequate resources to conduct investigations and the reluctance of potential witnesses to help identify suspects, among the reasons for the low homicide clearance rates.

Montoya said the Denver Police Department has put “a lot of work” into trying to establish better community relations, especially in areas where relationships are tougher between the police and residents.

“Trust is huge. Trust is what’s going to solve these cases,” Montoya said.

But Wellford said there is more to the story. “When it comes to improving homicide investigations, we often talk about the importance of external factors, like witness cooperation, as being key,” he said. But internal police practices are also critical.

“One of the key messages from the research is that if a police agency wants to prioritize clearing homicides, it needs to look internally, not externally,” Wellford said during a 2017 presentation at a conference on homicide investigation. “In other words, the things that police do—how they conduct the investigation, the steps they took during the process, the quality of their homicide units—those things can account for the differences between agencies that close cases and those that don’t.”

Left to Survive

Fard is reluctant to blame police or any other single entity for solving so few murders in his Five Points community.

“Yes, there’s historic mistrust of police… but it’s not just the police,” he said. “It’s more about the larger system being set up to fail particular people, communities, area codes.”

The violence, murders, failures to solve murders and so much more, Fard said, are about “the unfair distribution of resources.”

“This is a societal failure” that can only be remedied by everyone working together, he said. If communities were gardens, “you can expect the area that is watered to flourish. The area without resources is left to its own survival.”

Deborah Prothrow-Stith, MD, dean of the Charles R. Drew University College of Medicine in Los Angeles, said unsolved murders represent system failures up and down the line. “What unsolved murders indicate is that your government, your police force, your community, your society and supporters in a time of tragedy are not able to step up to the plate,” she said.

“If you add to that communities of color and urban poor, rural poor and disregarded communities that already don’t experience the full attention, support and resources of the government and of the police, it just feels overwhelming and makes people angry,” said Prothrow-Stith, a former Massachusetts Public Health Commissioner and nationally recognized expert on violence prevention and diversity.

In addition to ravaging communities, Prothrow-Stith said murders and unsolved murders can tear families apart, especially if endless trauma and grief lead to job losses, drug use and other problems.

“Not only do you have physical illnesses but you have divorce, you have economic impacts—all those things impact health,” she said.

Since 2010, the CBI’s cold case review team has helped local police resolve just five previously unsolved homicide cases. The bureau, which intervenes in cold cases only when requested by local police, also helped create new leads in several other cases, according to CBI investigative analyst Audrey Simkins.

While CBI has forensics and other tools to provide critical support in clearing old murder cases, it lacks the funding for cold case investigators.

“We do what we can to squeeze these cold cases in with the limited resources we have,” Simkins said. Since the cold case review team of investigators, forensics pathologists and other experts is strictly voluntary, it meets only two to four times a year, she said.

CBI Director John Camper said the bureau could accomplish a lot more with paid investigators, especially in rural areas where police may lack investigative resources. So far, requests for funding have been rejected by the state legislature, he said, adding: “We’ll keep at it.”

“The bureau is aware that families and loved ones of victims feel anger, disappointment and frustration—anger that someone could have killed their loved one, disappointment in the process and investigation, and frustration that the pieces aren’t falling together as they should, in particular that cold cases continue to rise even as efforts are made to reduce the numbers,” Camper told Hawkins and other victims’ families at a FOHVAMP meeting in the fall of 2018.

While families of unsolved murder victims try to remain hopeful, the reality is sobering. The longer a case drags on, the less likely it is to be solved. “As new cases of homicide occur, the older ones tend to get pushed down in terms of priority for police action and prosecutorial interest,” Unnithan said.

Still, time can work for investigators. New technologies can make old evidence useful, fresh eyes on an old case can uncover new leads, or changes in relationships between perpetrators and witnesses can mean witnesses will decide to talk, he said.

“There have been some spectacular successes in solving old cases,” said Unnithan.

Hawkins has taken comfort in hearing of recent cold case arrests across the country. “When I hear other cases being solved after some period of time, it definitely gives me hope for my son’s case,” Hawkins said.

His hope was revived recently when a new cold case detective in Denver notified him that evidence had turned up in his son’s case and was under review.

“It was a shock. They had never disclosed anything about crime scene evidence before,” Hawkins said.

“Even if it leads to something or someone, it won’t bring my kid back. But it’s important to hold someone accountable. Thirteen years is a long time.”