Deidre Johnson, who heads the Center for African American Health, at the nonprofit’s offices in Denver. Photo by James Chance

Deidre Johnson, who heads the Center for African American Health, at the nonprofit’s offices in Denver. Photo by James Chance

When Deidre Johnson gave birth to her first child—a baby boy—in July 2003, she and her husband were ecstatic. It had taken the 35-year-old a while to conceive, but the labor and birth had gone quickly and relatively smoothly. The new family of three went home the next morning.

By that afternoon, however, Johnson, who is African-American, was starting to feel ill. Her chest was hurting, and she was having trouble breathing. She drove herself back to the emergency room at the Denver metro-area hospital where she’d given birth. Hospital staff took her vitals, including her blood pressure. While her blood pressure reading was technically within normal limits, Johnson, a runner, knew it was too high for her—her blood pressure normally hovered at 90/70.

When Johnson, who holds degrees from Princeton and Yale, raised concerns about her blood pressure reading, a nurse dismissed her, saying: “You people always have high blood pressure.”

Johnson was told to go home and rest. By the next day, however, Johnson had developed a painful headache and was beginning to retain water. This time, when Johnson showed up at the emergency room, she was admitted immediately—her blood pressure was well beyond normal limits, she had developed swelling in her brain, and she was on the verge of kidney and liver failure.

The hospital ran countless tests, but a diagnosis remained elusive until Johnson’s father called a friend, an obstetrician, in California. The physician’s message was clear and urgent: “She has postpartum preeclampsia. She needs magnesium, or she’s going to have a stroke.”

Johnson recovered only after a week in the hospital’s intensive care unit.

***

Today, Johnson is CEO and executive director of the Center for African American Health, which provides culturally sensitive health education for African-Americans in the Denver metro area. (She also was formerly a program officer at The Colorado Trust.) Johnson is familiar with the statistics that show that Black mothers are at increased risk for postpartum complications and even death.

For Black women in America, pregnancy and childbirth can be dangerous undertakings, thanks to both the health effects of a lifetime of racism and a health care system that the evidence suggests continues to discriminate against people of color. This is true even for well-educated Black women. Despite educational attainment being a well-documented and significant social determinant of health, professional accolades can offer Black mothers little protection against dangerous complications of pregnancy and childbirth, or the vagaries of a medical system still plagued by conscious and unconscious racial bias.

“Even with an advanced degree, Black women have poorer outcomes than white women without high school diplomas,” Johnson says. “As the researchers splice and dice the data more, it’s becoming more and more clear that the stress of being a Black female in America affects outcomes.”

Nationwide, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the maternal mortality rate for African-American women—43.5 deaths per 100,000 live births—is over three times higher than the rate for white women. And in recent years, both the U.S. maternal mortality rate and the rate of severe maternal complications (such as the type Johnson suffered) have actually been on the rise for women of all races in the United States.

These grim racial disparities are echoed in infant outcomes. In 2016, the infant mortality rate for Black infants in the United States was 11.4 deaths per 1,000 live births—more than twice the rate of that for both Hispanic infants (5.0 deaths per 1,000 live births) and white infants (4.9 deaths per 1,000 live births).

The preterm birth rate, a major contributor to infant mortality, for African-American women is 14 percent, in comparison to only 9 percent for non-Hispanic white women.

Colorado generally ranks well, in comparison to other U.S. states, on measures of both maternal and infant outcomes. According to a 2017 publication from the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE), there were 145 pregnancy-associated deaths in the state between 2008 and 2013. (Pregnancy-associated deaths include all deaths in which the victim was pregnant, as well as deaths occurring within one year of the end of pregnancy, including those caused by factors unrelated to pregnancy, such as car crashes.) Only 21 of those 145 deaths were categorized as “pregnancy-related” (i.e., caused by a factor related to pregnancy).

The overall pregnancy-related mortality ratio in Colorado has, however, increased in recent years—from none in 2008, to 6.2 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2013, still significantly below the national average. Yet not all women in Colorado are impacted equally: those who die during or after childbirth, according to CDPHE, are also “significantly more likely to have a high school education or less, have incomes under $15,000 a year, live in rural areas, be unmarried, and be black.”

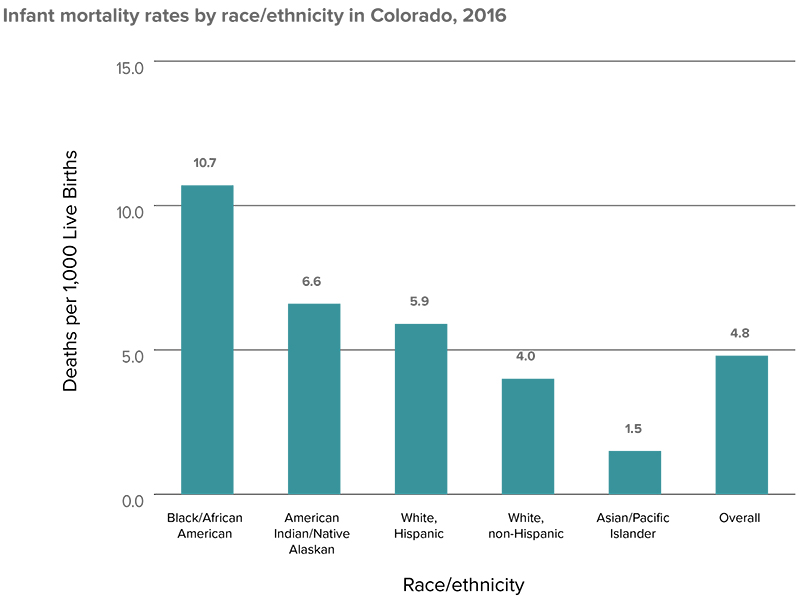

A fuller picture of racial disparities in maternal and infant health in Colorado emerges in the data on infant outcomes. In Colorado, according to data from CDPHE, the infant mortality rate among Black infants in 2016 was 10.7 deaths (per 1,000 live births), 5.9 for Hispanic infants and 4.0 for white infants, as the chart below illustrates:

Source: Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment

In Colorado, as in the rest of the country, prematurity (and related complications) is a major driver of infant mortality, accounting for 33 percent of deaths. And African-Americans in Colorado exhibited higher preterm birth rates—11.6 percent, as compared to 8.2 percent among white, non-Hispanic births—and higher rates of low birth-weight babies.

There’s little doubt that socioeconomic factors contribute to the worse maternal and infant outcomes observed among African-Americans, in both the United States and Colorado. African-American mothers are more likely than white mothers to live in poverty; more likely to live in low-income neighborhoods; less likely to have a college degree; and less likely to have health insurance and access to prenatal care—all factors that researchers have linked to poor maternal and infant health outcomes.

But a sizeable body of evidence has also demonstrated that wealth and education do not protect African-American women and their children. In a 1992 paper published in the New England Journal of Medicine, researchers compared infant mortality rates of Black and white infants with college-educated parents. They found that the infant mortality rate among Black infants with college-educated parents was almost twice as high as among white infants. The Black infants were also much more likely to have low birth weights, a factor the researchers identified as a major driver of the disparity in mortality rates.

In other words: Even when typically significant variables like educational attainment and wealth are not a factor, Black women and their newborns are still at a higher risk for worse health outcomes. And the stress from chronic exposure to racism is now suspected to be a root cause.

***

Thirteen months after her first harrowing experience as a mother, Johnson gave birth to her second child—another boy—at a different facility with a different obstetrician. Again, Johnson and her son were discharged quickly. And again, things went south shortly after she was discharged.

“I remember it like it was yesterday,” Johnson says. “I was in Toys ‘R’ Us buying a double stroller. And I remember just feeling this sudden weight on my chest and having to sit down.”

Once at the hospital, Johnson was admitted quickly. Despite her history of postpartum preeclampsia, however, a diagnosis and treatment was not forthcoming— as Johnson remembers it, the hospital was waiting for her obstetrician to show up and authorize treatment.

“The weird thing about it is that, even though they listened to me, they acted like I didn’t know what I was talking about,” Johnson says. “I kept telling them to look at my records—that this is what was happening. I told them I needed magnesium before things started to get worse. I was speaking their language. I was saying, ‘I’m starting to get a vascular headache. You need to get a urine sample because I’m sure I’m dumping protein.’”

Meanwhile, Johnson kept get sicker. At one point, she was admitted to a cardiac unit because her heart rate dropped to a dangerously low level. Again, it wasn’t until her father intervened—threatening to call a lawyer and file a lawsuit—that the hospital snapped into action, assigning her case to a new doctor (the hospital’s head of obstetrics), who promptly diagnosed her with postpartum preeclampsia and treated her.

“It was just so frustrating because I kept saying, ‘If you would simply look at what happened to me last time, you would know what to do,’” says Johnson.

“I don’t know enough about hospital culture and procedures to say with total certainty,” she says, “but my gut feeling is that I would have been treated very differently if I were a white woman.”

***

Researchers have amassed extensive evidence of racial bias in medical care, including the kind that Johnson believes she experienced. A lengthy report published in 2003 by the Institute of Medicine of the National Academies of Sciences concluded that “[a] large body of published research reveals that racial and ethnic minorities experience a lower quality of health services, and are less likely to receive even routine medical procedures than are white Americans.”

Beyond the health care bias, researchers also now suspect that the racism Black women experience in their day-to-day lives, even before they’re pregnant, damages their health and that of their children—the epitome of what is now widely known as “toxic stress.” Martha Hargraves, a professor emeritus at the University of Texas and a co-author (with Carol Hogue, one of the authors of the 1992 NEJM paper on infant mortality, and Karen Scott Collins) of a book called Minority Health in America, has studied both historic and current racial disparities in infant mortality.

“There are just so many stresses that African-American women experience,” explains Hargraves, who is African-American. Some of the many examples: “Not having a safe place to live; not being able to walk on the street without worrying about your safety; worrying about not having your husband or significant other come home if he’s the wrong color; not being able to work your way up the professional ladder, or to not see anyone that looks like you working their way up the ladder.”

Researchers like Hargraves theorize that the toxic stress of a lifetime of those discriminatory interactions can affect maternal and infant health—predisposing African-American women to trauma-related mental health issues and complications such as preeclampsia and preterm birth. In a review paper for Epidemiological Review, Hogue and Michael R. Kramer highlighted a number of papers that have documented a link between reported experiences of racial discrimination and low birth-weight rates and preterm birth rates; two such studies found a “40%–80% elevated risk of preterm birth associated with perceived racism or discrimination.”

Like most Black Americans, Johnson has experienced racism from a very young age.

When Johnson was six, her father, a successful entrepreneur, broke a racially restrictive covenant to become the first African-American to purchase a home in Denver’s upscale Crestmoor neighborhood. The family’s new neighbors made it clear that Johnson and her family were not welcome.

It took Johnson decades to realize that her bone-deep reluctance to socialize with neighbors over the years likely stemmed from those early experiences. It took her just as long to process how a lifetime of those kinds of experiences may well have contributed to the postpartum preeclampsia she experienced after the births of her children.

“There are so many things you’re just used to navigating and dealing with—it becomes your normal,” said Johnson, reflecting on how life experiences may have affected her health. “You’re like the frog and the boiling pot, and you just adjust and don’t realize the damage it’s doing to you while it’s happening.”

The pathways through which stress may impact maternal and infant health outcomes are myriad. Arlene Geronimus, a professor at the University of Michigan, first proposed her theory of “weathering” in 1992, hypothesizing that “the health of African-American women may begin to deteriorate in early adulthood as a physical consequence of cumulative socioeconomic disadvantage.” The theory stems from the fact that African-American infants born to teen mothers exhibit lower mortality rates than those born to older mothers (the reverse is true for white infants).

“Aging, of course, increases the risk of maternal morbidity, and as a result infant mortality and morbidity,” explains Carol Hogue, now a professor at Emory University. “Even just by chronologic age, older women are at greater risk of death and having pregnancies that are complicated. But this aging process is speeded up when women have to deal with extra stresses.”

Researchers have also begun to explore other pathways through which the toxic stress of racism may drive poor outcomes. Hogue, for example, is an investigator on a project focused on the microbiome, and on another project focused on the epigenetic determinants of preterm birth. She is also exploring in her research how infection and inflammatory processes may contribute to racial disparities in outcomes.

But for all the unanswered questions that remain, Martha Hargraves points out that there are plenty of things that providers and public health officials can do now to affect change.

“We need to look at social supports that reduce some of the stressors of working two jobs and of facing discrimination at work,” Hargraves says. “We need to look at developing new tools for identifying high-risk pregnancies and incorporating the weathering hypothesis into that assessment. We need to do a better job at conducting research on the causes of prematurity by expanding the model to include social context. And we need to have a look at alternative medical approaches that we do not currently utilize but have proven historically to be effective.”

Listening to Black women might be another good place to start.

“One thing that I was clearly aware of was that I wasn’t being listened to [by hospital staff]—my knowledge of my own body and person was ignored,” Johnson says. “I remember seeing the notes that they took in my [hospital] chart the second time. … They described me as a very affable, educated African-American woman. But they still didn’t listen to me.”

As the leader of the Center for African American Health, Johnson is working to shift the health care system’s treatment of Black patients at all life stages. The Center currently deploys community health and patient navigators to help patients communicate constructively with their health care providers, and is arming patients with more information about the effects of toxic stress. Johnson says that providers also need to approach Black patients differently.

“Doctors need to keep in mind that everybody has a story, and they need to get to know the patient rather than bringing in all these assumptions,” Johnson says. “You can’t help people you don’t see.”