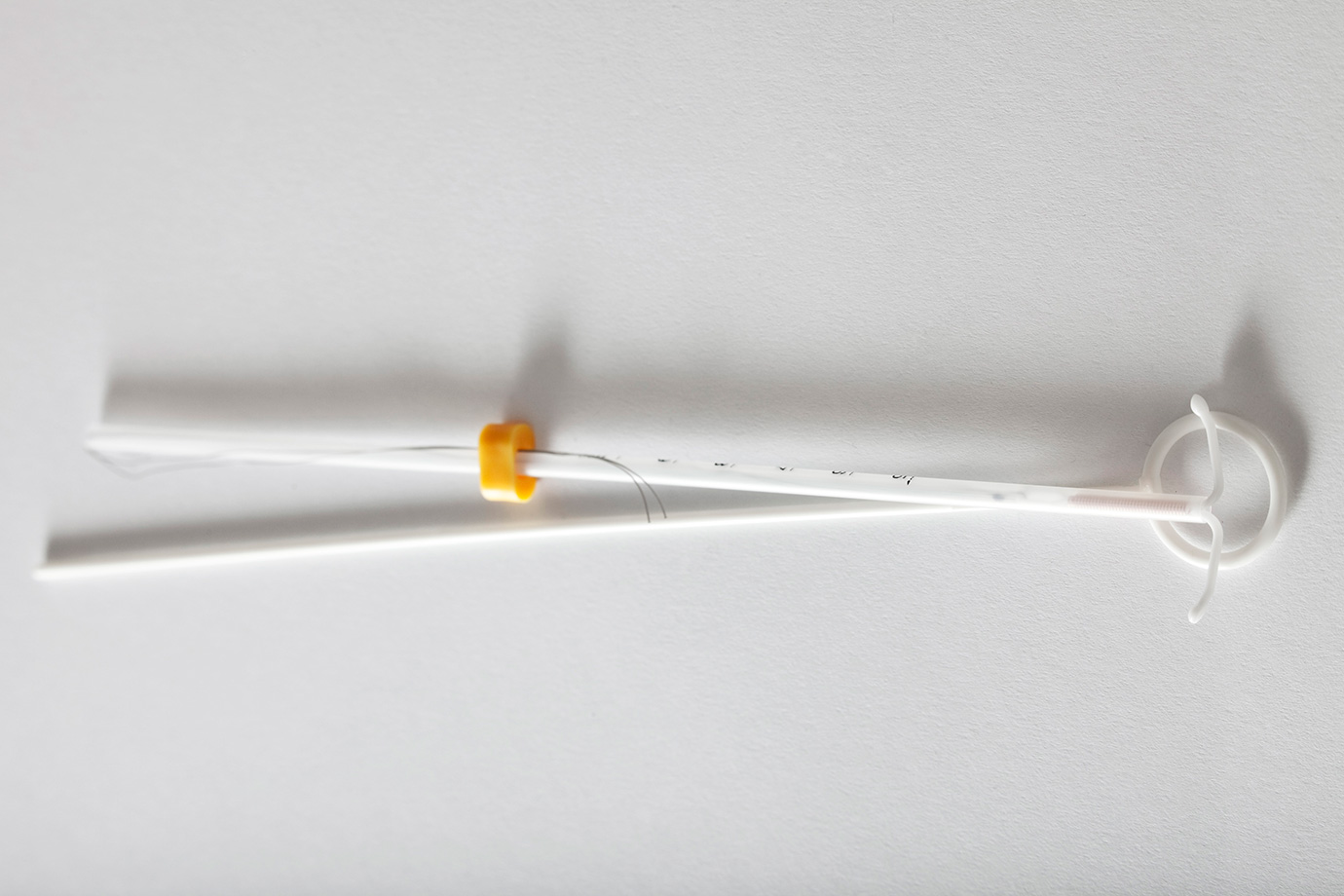

Intrauterine devices and other long-acting forms of birth control are among the most effective ways to prevent unwanted pregnancies. Photo by imagepointfr via Depositphotos

Intrauterine devices and other long-acting forms of birth control are among the most effective ways to prevent unwanted pregnancies. Photo by imagepointfr via Depositphotos

A Colorado initiative to increase access among teenagers and poor women to the most effective methods of reversible birth control was covered by The New York Times recently, with the headline “Colorado’s Effort Against Teenage Pregnancies Is a Startling Success.”

The story heaped praise on the six-year effort, reportedly funded by the Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation, to give free access to intrauterine devices (known as IUDs) and implants that provide nearly failsafe protection against pregnancy. Other national media outlets piled on.

While teen birth rates have dropped around the country, the drops in Colorado have outpaced the national average, the Times and others noted. Births to Colorado mothers aged 15 to 19 dropped 40 percent from 2009, when the Colorado Family Planning Initiative went into effect, to 2013, according to data compiled by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment.

By comparison, the national teen birth rate decreased 30 percent during that period, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

But the national coverage glided over some important details. Remarkably, the data show that Colorado’s experiment seems to have been even more successful that it looks: it had a disproportionate effect on some of the girls and women at the highest risk for unplanned births, and families who are most vulnerable to negative health impacts.

1) The birth rate among young Hispanic teens dropped 50 percent

In 2009, the year the initiative went into effect, there were 1,265 babies born to young Hispanic teens in Colorado, i.e. those between the ages of 15 and 17. In that year, the state’s young Latina teenagers were having babies at nearly six times the rate of young white teenagers.

By 2013, there were more young Hispanic teens living in Colorado. But they had many fewer babies that year—just 690. Their pregnancy rate fell by half since 2009, at a rate nearly twice as fast as the decrease during the previous five-year period.

A disproportionate number of clients at the family planning clinics that offered free IUDs and implants were Hispanic, notes state public health demographer Sue Ricketts.

That’s despite initial concerns among the program’s organizers that Hispanic women would be less likely to choose the long-acting methods.

Stacy Herrera, clinic program manager for the Pueblo City-County Health Department, says many of the Latina teens that her clinic served were indeed initially hesitant to choose implants or IUDs over other forms of birth control. They had misconceptions that their fertility would be affected, or that they’d have other negative health impacts.

Later, says Herrera, young Latinas started asking for the devices.

“They could come in, and again and again tell us, ‘my cousin has it, my aunt has it,’” says Herrera. “It became socially acceptable. It wasn’t that scary device.”

Maria, 16, is going into her senior year of high school in Pueblo. (We are using a pseudonym to fully protect her privacy.) She received the Nexplanon implant in September to ease painful cramping, and she said she’s happy with it.

“I plan on having a kid, but not soon,” she says. “I want to travel the world. I want to get through college.”

2) Many of the girls and women served are uninsured

The family planning clinics offering the IUDs and implants serve everyone, regardless of their ability to pay or their immigration status. That includes clients who gained insurance under Medicaid during the last several years, or are eligible for subsidized insurance from Colorado’s exchange that provides access to long-acting birth control.

It also includes undocumented immigrants, who are ineligible for Medicaid and don’t qualify for tax subsidies for private insurance. And it includes clients who cycle in and out of Medicaid eligibility as their income fluctuates, and people who don’t want to put birth-control devices on their insurance for fear of their parents or partners finding out, according to state health department officials.

Without help, IUDs and implants can cost between $400 and $1,000.

In short, the program provided the most effective—and expensive—birth control options to girls and women who wouldn’t otherwise be able to afford it.

3) Unplanned pregnancies carry risks to mothers and babies

Unintended pregnancies are associated with delayed and inadequate prenatal care, and with premature birth. Teen pregnancies, especially when they’re unintended, often interfere with the mothers’ educational goals, like finishing high school or college.

The rates of unintended pregnancy are especially high among young and low-income women.

“There’s a tendency to blame the victim and say they wanted to have children,” says Ricketts. That’s not true, she says. “People want to have sex. They don’t want to have kids.”

One of the effects that Ricketts and her colleagues measured in their study of the Colorado Family Planning Initiative published last year was enrollment in the Special Supplemental Nutritional Program for Women, Infants and Children, or WIC. They found that infant enrollment in WIC fell 23 percent between 2010 and 2013.

The economic recovery explained some of that fall, but not all of it, says Greta Klinger, the family planning supervisor for the state health department, who co-wrote that study.

“Nationally they were seeing a decline—but nowhere near like Colorado saw,” says Klinger.

In the long-term, fewer unintended pregnancies means fewer babies born into poverty. And that can only have a positive effect on the health and well-being of mothers and children.