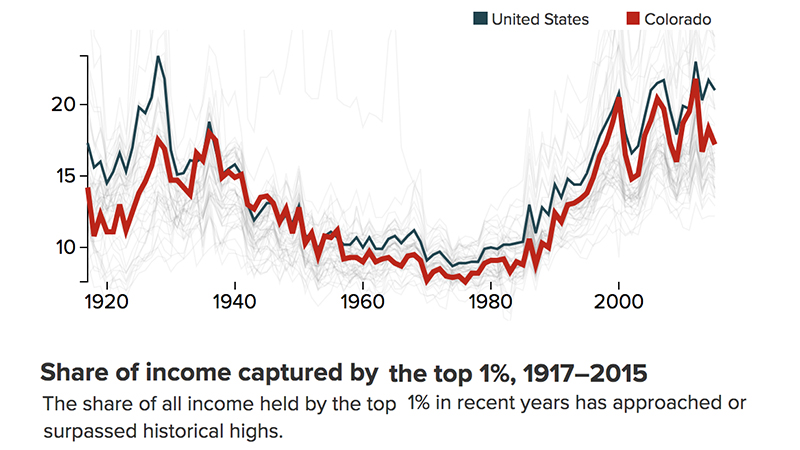

Share of income captured by the top 1%, 1917-2015: The share of all income held by the top 1% in recent years has approached or surpassed historical highs. Source: Economic Policy Institute

Share of income captured by the top 1%, 1917-2015: The share of all income held by the top 1% in recent years has approached or surpassed historical highs. Source: Economic Policy Institute

In Colorado, the top 1 percent make, on average, $1.3 million a year. That’s more than 20 times the average income of everyone else—$61,165.

This discrepancy puts Colorado 20th in the nation in terms of state income concentration and squarely within a national trend of growing income inequality, according to a recent study from the Economic Policy Institute (EPI).

“We have national work on the trends of income concentration, which generated comments of, ‘Well, that’s just New York City, or that’s just Silicon Valley,’” explains study author Mark Price, PhD, a labor economist at the Keystone Research Center, a Pennsylvania-based research and policy development organization that was the impetus for the local-level report. “What drew us to do this at a state level and expand it to counties is precisely so that we can have something to say about whether the trends across the U.S. are also showing up in your neck of the woods.”

The report is the fourth of its kind from EPI, and remains consistent with previous findings showing steady, widespread growth in income inequality across the country. “We’ve seen a steady flow of rising income concentration,” says Price.

The main implication is that, after the big-bank bailout of 2008, the United States is still in an era where the top 1 percent of families in most states are taking home a disproportionate share of income.

The issue isn’t just about economics, though. Research suggests that living in a community with high income-inequality harms the health of the overall population. A 2015 study from the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute revealed that “people in unequal communities were more likely to die before the age of 75 than people in more equal communities, even if the average incomes were the same,” reported The New York Times. This confirmed previous data, including a 2001 study published in the American Journal of Public Health that found people living in states with high income-inequality had a higher risk of mortality compared to people in more equal states.

To better understand the EPI data and its implications, it’s helpful to understand the historical context. The U.S. went through a period from 1945 to 1973 where the economy expanded, GDP grew and income growth was more broadly distributed, Price says.

In other words, “the percent change in income growth that a CEO experienced was roughly equal to the percent change in income growth that a janitor experienced,” says Price. “In fact, folks at the bottom did a little better than folks at top.”

During this period, “the economy grew more, performed better, and was also more equal,” says Price, compared to the period that followed. In the new economic era—which began around 1973 and continues today—income growth stopped flowing evenly across economic classes and instead was diverted primarily to those at the top. (Price and other researchers characterize this economic transition in the United States in the early to mid 1970s as being due to a combination of less frequent minimum-wage increases, more hostility to unions by employers and the government, and deep cuts in taxes for the very wealthy. More on these issues later.)

This national narrative is reflected in Colorado-specific data. In 1945, for example, the top 1 percent of Colorado families took home 4 percent of the state’s total income, with the remaining 99 percent earning 96 percent of all Colorado income.

Yet since 1973, the top 1 percent of Colorado earners have taken home 43 percent of the state’s total income, leaving just 57 percent for everyone else.

Though Colorado’s income inequality isn’t as severe as other states, like New York, it’s followed the same pattern: as the economy has grown, the income growth has been concentrated for a tiny share of people at the top.

“This is not just a story of Silicon Valley,” says Price. “It’s a story that’s impacting the state of Colorado.”

Look across the state and you’ll see a pattern mimicked across the country, says Price: “While [Colorado] ranks in the middle of states on the ratio of inequality, you’ve got some places that are even more substantially unequal.”

This is especially evident near some mountain resorts. Pitkin County, home to Aspen, and San Miguel County, home to Telluride, have two of the nation’s highest gaps in average income between the top 1 percent and the bottom 99 percent of earners.

“A lot of these resort communities have popped up in data sets,” says Price, and indicate, among other things, a pattern of “very high-income people living far away from where they make their money.”

The presence of these resort communities puts Colorado “in the company of Wyoming and Florida,” says Price, two other states with a notable concentration of high-end resort communities. The inequality ratio in Wyoming and Florida rank them in the top five nationally.

When considering the metropolitan areas in Colorado, Glenwood Springs (a 45-minute drive up the Roaring Fork Valley from Aspen) is the most unequal of all 20 metro areas in the state, with the top 1 percent of earners making 45 times more than the bottom 99 percent ($2.9 million versus $66,000). The Denver metro area ranks seventh, with the top 1 percent earning 19.8 times more than the bottom 99 percent ($1.3 million versus $68,000).

Across both rural and metro areas, several factors likely contributed to this increased concentration of income among the highest earners, says Price.

The first: the minimum wage.

“From 1945 to 1973, the U.S. as a whole was characterized by a minimum wage that was rising federally and pushed the low-wage worker to receive about half the income of the middle class,” says Price. “During this period, union membership was at a peak across states, as were high tax rates on the highest-income earners, sometimes at rates of more than 70 percent.”

But since 1973, the power of the minimum wage has fallen, says Price. Today, the typical low-wage worker makes one-third the amount of a middle-wage worker.

On top of that, when comparing our current economic era to the pre-1973 one, union membership has fallen nationwide, which makes companies less likely to invest in higher wages for their workers. Lastly, federal policy changes have made tax rates on the ultra-wealthy “much lower today than they used to be,” says Price, which only increases income inequality.

“Compensation at the top among chief executives and folks in the financial sector sets the tone for the whole economy,” says Price. High compensation in these realms can drive high compensation for leadership across other industries and organizations.

These trends are especially troubling as “speech is basically money,” says Price. “Whether you’re on the right or the left, having tremendous income and wealth gives you an outsized voice in the political process.”

What’s more, unequal, concentrated income gain is “counter to the idea of the American dream,” Price adds, as it furthers class divides. Instead, “we should be concerned about making sure we have more access to opportunity for low- and middle-income kids,” says Price.

There are several plausible solutions that could dilute this concentration, says Price, including increasing the federal minimum wage to narrow the distance between middle- and low-wage workers; implementing policies that expand worker voices in corporate governance to restrain executive pay; and raising taxes on the highest-income individuals. Taken a step further, the additional tax dollars generated could be used to fight inequality through financial aid expansion for low-income college students and increased access to early childhood education.