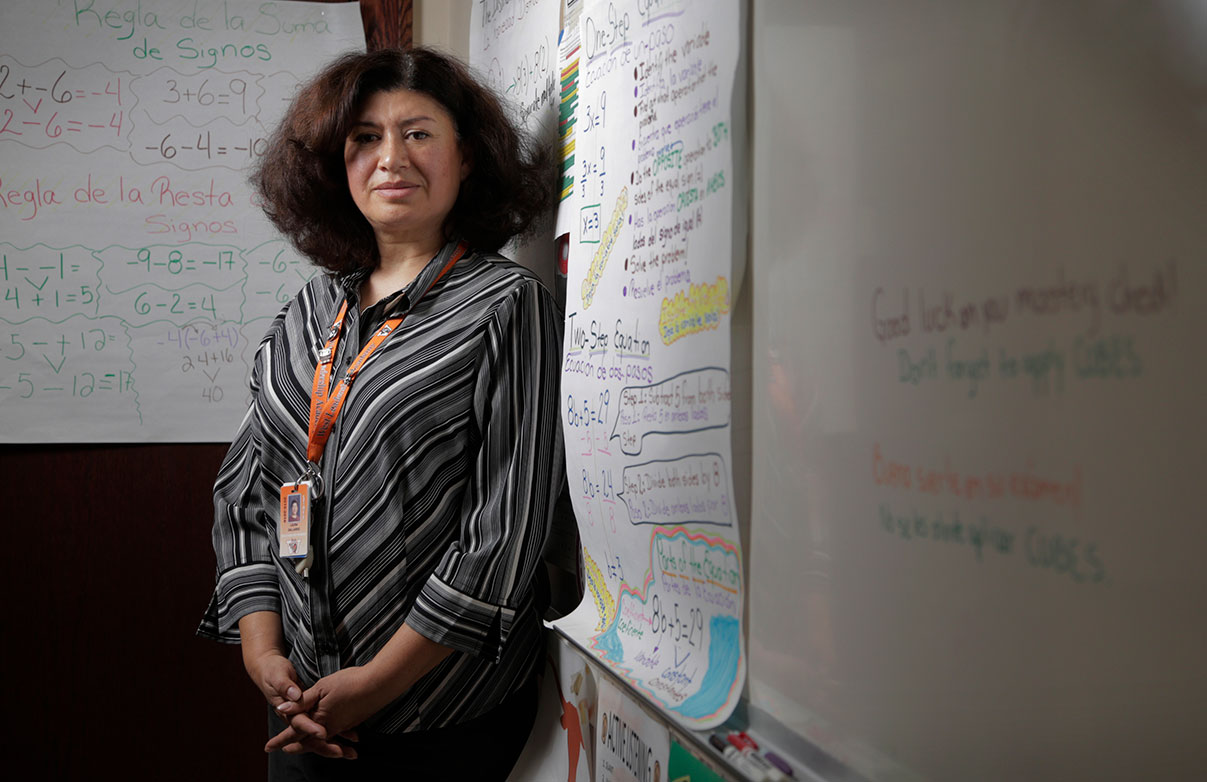

Laura Gallardo wasn’t using her skills as a chemical engineer after she immigrated to Colorado from Chihuahua, Mexico. Photo by Joe Mahoney

Laura Gallardo wasn’t using her skills as a chemical engineer after she immigrated to Colorado from Chihuahua, Mexico. Photo by Joe Mahoney

Laura Gallardo is a trained chemical engineer, able to perform quality control on products for multinational companies in their food labs. But she didn’t want to put her bachelor’s degree on her resume 20 years ago, after she fled the violence of Chihuahua, Mexico and moved to the United States, where the only jobs she could get without speaking English were working the grill at McDonald’s and Burger King.

“I feel ashamed trying to apply to a job that wasn’t in my career,” Gallardo said, now with near-perfect command of English.

She was unhappy, eating fast food for three meals a day, not taking care of her health and feeling like she wasted her time and went to college for nothing.

“I was really, really frustrated,” Gallardo said.

She was experiencing what’s known as “brain waste”—that is, highly skilled professionals working low-skilled jobs. In Colorado, 27 percent of people born abroad have a bachelor’s degree or higher, according to 2015 American Community Survey estimates, compared with 39 percent of the state as a whole. But they’re less likely to have a career relevant to their education than American-born bachelor’s degree holders.

Barriers include English-language proficiency, proving foreign credentials and education are up to U.S. standards, passing professional licensure and certification exams, lack of social networks, and discrimination.

Approximately 23 percent of foreign-born college-educated people in Colorado are unemployed or employed in low-skilled jobs, compared with 19.5 percent of U.S.-born workers, according to an analysis of census data by the Migration Policy Institute. Colorado’s gap is smaller than in neighboring Utah and Wyoming, where more than 27 percent of college-educated immigrants are underemployed, according to the group’s research.

Socio-economic status, social networks and job quality and working conditions are social determinants of health—that is, structural and social factors that influence the health of an individual and community.

Researchers have sliced the question of how work affects someone’s health and well-being in a lot of ways. Workers with higher socio-economic status are generally healthier than lower-paid and lower-status workers. A Canadian study found university-educated participants who were overqualified for their jobs were more likely than their peers to report declines in their health over a four-year period. Meanwhile, researchers are still parsing out what happens to immigrants’ health specifically when they experience downward mobility in their professions.

Some Colorado organizations are working to help foreign-trained professionals overcome brain waste and return to their fields. The services include career counseling aimed at explaining sometimes-confusing cultural differences, and helping to navigate red tape, such as how to succeed in licensure and certification exams, network and interview for jobs, improve English skills or obtain good professional recommendations.

Gallardo sought help from the Colorado Professional Latino Advancement Network (CPLAN), which helps mostly Latin American professionals trained in education and engineering transition back to their fields of expertise.

For Spanish-speaking clients, many can only find work in Spanish-language environments and rarely have the opportunity to gain or strengthen workplace English-language skills, CPLAN founder Maria Young said. Male professionals can find work in construction and “make pretty good money,” she said, but many still want to shift to a white-collar career track, even if it includes an initial pay cut.

For some, such a move may ease the embarrassment of a job title that doesn’t fit their education and skills, Young added: “The major thing I see is having pride again.”

Still, only a fraction of her clients regain their full professional status. Instead, many find work as a paraprofessional, such as an assistant teacher or paralegal, or patient navigator helping other immigrants with an unfamiliar American health care system.

Gallardo has found a second passion as a math teaching fellow at Denver Public Schools. She connects with the students, but is still evaluating if her future lies in teaching or in engineering. CPLAN helped her gain accreditation for her education. Gallardo is happy again, she said.

“Oh my God, it’s like your soul coming back to your body,” Gallardo said.

The Colorado Welcome Back Center also has a program to help professionals like Gallardo. The center focuses on foreign-trained professionals mainly from health care fields, and is one of 11 in the Welcome Back Center network across the United States. Since 2013, 712 people from 95 countries who speak more than 120 languages have sought help from the center, Program Manager Ben Jutson said.

Most clients—approximately 75 percent—are unemployed when they approach the center, Jutson said. So far, approximately 26 percent of clients have obtained full-time job placement in the health care field, earning an average of $37,000 a year, Jutson said, while professionals—such as nurses and the 19 foreign-trained doctors the Welcome Center has placed in medical residency programs—earn more.

As more immigrants enter the medical profession, patients may also stand to gain. Treatment by medical professionals with backgrounds that reflect their patients has been shown to promote patient satisfaction and communication, while language barriers have been shown to harm patients.

The certification process for aspiring physicians born and educated in the U.S. is no easy task—including passing the U.S. Medical Licensing Examination, and competing for a medical residency spot—let alone if you are from a foreign country.

The licensure process itself is rife with barriers for immigrants specifically, Jutson said, from cultural misunderstandings to the minutia of testing rules and the cost of exams.

Residency slots are much more difficult for foreign-trained medical graduates to obtain, as preference is often given to U.S. graduates. Once on the job, one study found that professional barriers and discrimination faced by foreign-trained doctors mirrored the experiences of other marginalized social groups.

“No matter how good you are as a doctor, as an international doctor you’re always different,” said former Colorado Welcome Back client and rock climber Dr. Martina Mali, originally from Slovenia, who is now a medical resident at Texas Tech University in El Paso. She speaks English with a heavy accent, which she said prejudices others against her.

Mali migrated to the U.S. after she met her husband on a rock climbing trip. Her work as a climbing coach at a gym in Boulder, Colo. helped her network with doctors, which led to job shadowing opportunities and eventually recommendations that helped her land a residency slot.

“It doesn’t matter what kind of training you have back at home—it could be chief of surgery—you have to start at the beginning here,” Mali said.

Brazil-native gastroenterologist Dr. Vivian Ussui sent out 130 applications, costing $2,200, and traveled to New York, Connecticut and Denver, before finally securing a residency spot in Miami.

The effort will likely pay off in the end. Once Ussui graduates from residency and gets a job, she’ll be able to earn more money and better provide for her family.

“With that, my kids can go to a good school and I can start paying for college,” she said.