Photo via GraphicStock

Photo via GraphicStock

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has described oral health disparities in the United States as “profound.” Your race, socioeconomic status, gender or where you live are all related to your risk of having untreated tooth decay, periodontitis and other oral health problems.

Oral health is widely regarded as a reliable indicator of overall physical health status. “What is going on in your mouth affects the entire person,” says Christy Dodd, executive director of Oral Health Colorado.

Dodd cites links between poor oral health and heart disease, diabetes, challenges attaining employment and more. Poor oral health among pregnant women has also been linked to preterm and low birth-weight newborns.

It has been more than three years since Medicaid expansion in Colorado began under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which added approximately 289,000 enrollees and also expanded dental coverage to many who previously lacked it. This included Christopher Smith, a student at Northeastern Junior College who also works at the Family Resource Center in Sterling.

Being HIV positive, access to health services, including oral health care, is particularly important to Smith. People with HIV/AIDs often experience mouth dryness (which places them at a higher risk for tooth decay) and, because of immune system compromise, are at a higher risk for periodontitis, cavities, oral warts and ulcers.

“I can honestly say that I would not have the health I have today if it wasn’t for Medicaid,” Smith says. His previous employer didn’t provide dental coverage, and Smith couldn’t afford to pay for dentist visits out of pocket. “My oral health had deteriorated so much that I eventually had to have a significant number of teeth extracted,” he says.

Smith credits Medicaid’s dental coverage with allowing him to get care, including bridges and partial dentures, that has helped preserve and maintain his remaining teeth.

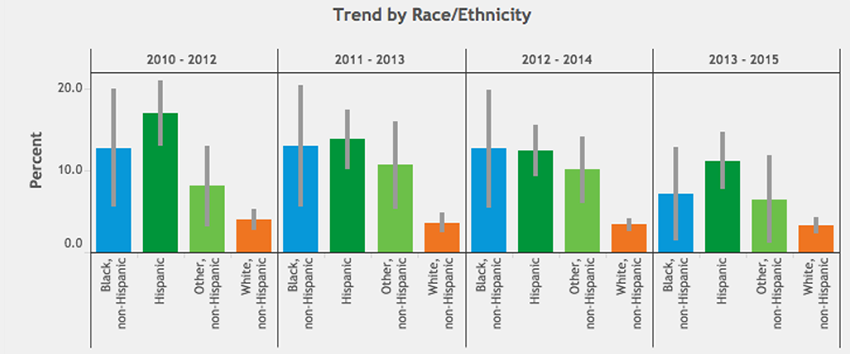

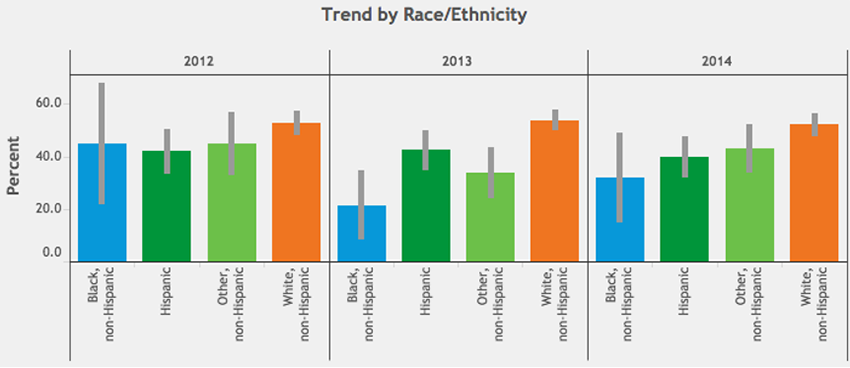

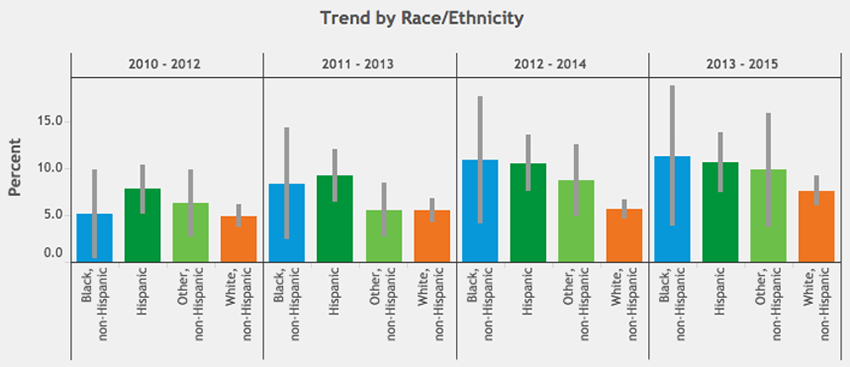

Yet even with Medicaid expansion, preliminary data from the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE) suggest that, while some gaps may be narrowing, other disparities in oral health outcomes persisted from at least 2010 to 2015:

Figure 1: Percentage of Colorado children with teeth in fair or poor condition. (CDPHE VISION, 2017)

Figure 2: Percentage of pregnant women in Colorado having their teeth cleaned by a dentist or dental hygienist. (CDPHE VISION, 2017)

The CDPHE data show that more blacks and Hispanics than whites in Colorado reported having children with teeth in only fair or poor condition from 2010 to 2015, though this rate has decreased in recent years across all races and ethnicities (Figure 1). Meanwhile, during pregnancy, when women can be at an increased risk for tooth erosion and cavities, white Coloradans reported having their teeth cleaned more than any other racial/ethnic group (Figure 2), and this disparity may be worsening.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, “dental insurance is a main driver” of these disparate outcomes, according to Sara Schmitt, community health policy director at the Colorado Health Institute (CHI), a Trust grantee. And while Medicaid expansion increased coverage statewide, there are still geographic disparities in dental insurance rates across Colorado.

According to CHI’s biannual, Trust-supported Colorado Health Access Survey (CHAS) results for 2015, around 87 percent of residents in Douglas County reported having dental insurance—the highest rate of any Colorado county. Meanwhile, less than 60 percent reported having dental insurance in rural southwest and northwest Colorado counties. The difference was even larger among seniors: While 64 percent of adults over 65 in Douglas County said they had dental insurance, only 28 percent in Mesa County did.

Statewide, along ethnic lines, dental coverage was slightly lower among Hispanics, and they were less likely to report good oral health compared with whites, the latest CHAS found.

The last two iterations of the CHAS have found disparities not only in oral health status and coverage, but also in access. In Douglas County—the highest-earning county in Colorado—coverage and provider visit rates have improved since 2013. Other less financially prosperous counties have not fared as well: El Paso County has seen reductions in both dental coverage and provider visit rates in the last four years.

While having dental insurance is associated with visiting a dental provider, access remains challenging in parts of Colorado. According to the 2015 CHAS, higher percentages of residents in places like the Denver metro area visit a dental professional regularly than in places like the San Luis Valley and northeast Colorado. The CHAS also found that statewide, the number of Hispanics seeking oral health care is lower than whites.

“You might have access to the best insurance in the world—but if you don’t have a provider there to even take it, then that’s not an option for you,” Schmitt says.

Along these lines, CHI found that factors such as the availability of dental providers, as well as the insurance types they accept (i.e., private versus public plans), impact whether children have access to dental care. These factors may explain why delayed access to dental care is highest among black and Hispanic children, another disparity that has persisted—and perhaps even worsened—despite expanded Medicaid coverage (Figure 3), according to initial CDPHE data.

Figure 3: Percentage of Colorado children delaying needed dental care. (CDPHE VISION, 2017)

How can Colorado close these gaps? The ACA Medicaid expansion is still only a few years old, so it’s possible it could just take more time to see such effects. Dodd believes that simply adding dental coverage for pregnant women to Child Health Plan Plus can significantly reduce oral health disparities in Colorado. She also recommends public-health campaigns to encourage the population to drink more water and fewer sugary drinks.

Community water fluoridation remains an obvious but essential avenue for impact. Dodd says studies have found a $38 savings on oral health expenses for every dollar spent on fluoridation, and it could help close rural-urban oral health disparities. According to Dodd, while all of the Denver County communities have fluoridated water, three of 35 communities in Weld County, two of five in Alamosa County and 21 of 55 in El Paso County—including Colorado Springs and the nearby military bases—do not. She also points out that Sedgwick County has neither fluoridated water nor any dental providers.

Katya Mauritson, the state dental director and oral health unit manager at CDPHE, also draws attention to the need for more equitable data collection, plus more resources for community-level data collection, in order to design more effective oral health interventions. She notes that the CDPHE county-level data for African Americans, as well as statewide data for Asian Americans or American Indians, cannot usually be collected due to small population sizes.

Mauritson points to a recent Indian Health Service survey finding that 54 percent of American Indian/Alaska Native children ages 1-5 have experienced tooth decay—a rate similar to Colorado’s Hispanic population. Yet such data are not being reported at a statewide level.

The current political climate has heightened uncertainty about the fate of the ACA and health care, including dental coverage for those who need it most. Says Dodd: “If the [federal government] repeals the ACA, the issue may come down to what services they can cut—and it is highly likely that they will look at the [Medicaid] adult dental benefit.”

Smith drives home what this could mean to him and others: “I have benefited from Medicaid… financially, physically and emotionally. Since my HIV diagnosis, I have been able to get medical care at an affordable price. Since then, I have been able to maintain my physical health, which makes things less stressful and improves my quality of life.

“It is a full-circle kind of thing.”