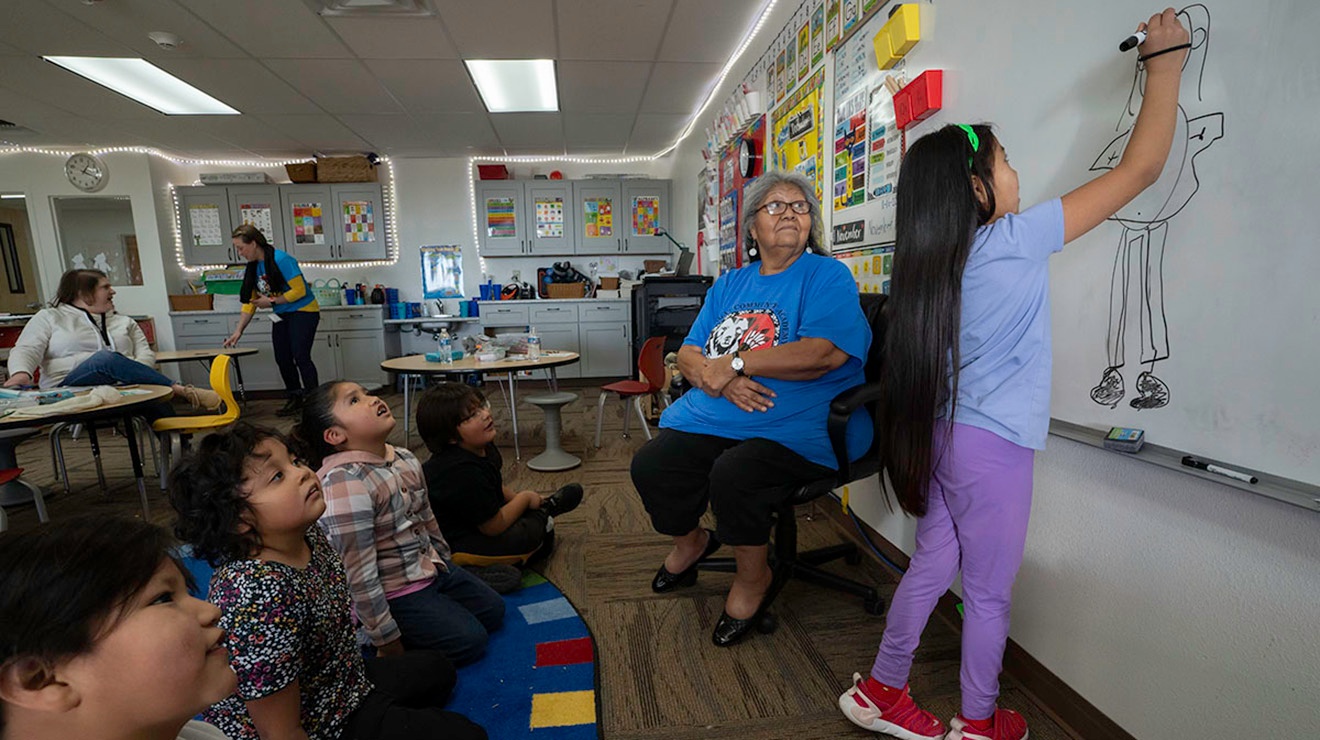

First-grade student RedSky Lang draws on the whiteboard during a Ute language vocabulary game led by Betty Howe, a Ute Mountain Ute tribal elder and Ute language teacher. Photos by Shannon Mullane / Special to The Colorado Trust

First-grade student RedSky Lang draws on the whiteboard during a Ute language vocabulary game led by Betty Howe, a Ute Mountain Ute tribal elder and Ute language teacher. Photos by Shannon Mullane / Special to The Colorado Trust

Twelve miles south of Cortez, in the southwest corner of Colorado, a right turn on Mike Wash Road leads three miles up to the town of Towaoc on the Ute Mountain Ute Reservation.

Towaoc is pronounced toy-awk. The town is due east of the cliffs that form the “toes” of the sacred Sleeping Ute Mountain, a 9,984-foot peak with a profile that is said to resemble a Ute Indian chief resting on his back with his arms folded. About 1,200 people live in Towaoc. It’s 22 miles as the crow flies to the Four Corners National Monument.

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe manages a 7,700-acre farm and ranch. The tribe runs a casino, hotel, and a gas station and travel center along the highway. There are plans to build a tribe-owned grocery store. Towaoc has a 54-bed prison, run by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and a U.S. Post Office.

And now, a school.

Kwiyagat Community Academy (KCA), opened in September 2021, is Colorado’s first charter school located on a Native reservation. In the Ute language, kwiyagat means “bear.” The hope is that the school will keep the Ute language and culture alive and strengthen the Towaoc community, too. Towaoc is the poorest zip code in Colorado, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, with 37% of families living below the poverty line.

The first 16 months suggest the school is taking root, with enrollment and community-wide enthusiasm as the key measures of success. The school is a lively focal point of activity on the southern end of the small downtown square.

But challenges remain. There are complicated layers of governance—tribe, state, federal government, and the school’s authorizer, the Colorado Charter School Institute. There is the challenge of finding licensed, qualified teachers to work in this remote corner of Colorado. (Teachers need not be Native, nor speak the Ute language.)

And there is the task of lifting student achievement—a chronic statewide and national issue for Indigenous students. Improving results on statewide tests goes hand-in-hand with another long-term concern: attendance.

But the overall mood is optimism.

“Before the school opened, I do kind of feel like we were forgotten,” says kindergarten teacher Nena Lopez, who lives in Towaoc. “And now, you know, with a charter school that brings a lot of state representatives here, it’s been really, really an eye opener. For not just the state, but for the community, too.”

Kimberly Wing and her daughter Starlena, a first-grade student, head home after a school day at Kwiyagat Community Academy.

Beginning as a kindergartener and all the way through high school, Dyllon Mills, a member of the Ute Mountain Ute tribe, made a daily trek on a bus north to schools in Cortez. The distance wasn’t bad, he said, but it was a matter of preparing his mind each day to try and fit in.

When Towaoc youth climbed off the school bus, he says, “we knew we had to act a different way. There were different values and acceptable thoughts, which was not the same as where we grew up.”

Now, six months after graduating from Fort Lewis College in Durango, Mills is vice-chair of the KCA school board and working for the Southwest Area Health Education Center. The KCA school board includes three Ute tribal members and two members who are not Native but who have worked with Native students in the Cortez school system. The KCA school board was appointed by the Ute Mountain Ute Tribal Council.

Tina King-Washington, president of the KCA school board and a Ute tribal member, says that for students the daily trip to Cortez was “like going to a different country.”

Kwiyagat Community Academy is small. During the 2022-23 school year, the school is serving 48 students from kindergarten through second grade. That’s three students above projections. School leadership views the added enrollment as a vote of confidence.

“If you look at the Montezuma County numbers, there’s been a dip in the school-age population,” says KCA Principal Danny Porter. “So I think the word is spreading. I think people are seeing what’s going on and I think we are building that trust with the community.”

Next year, KCA will add third grade. The school will grow, in the subsequent two years, to serve fourth- and fifth-grade students, too. The public school is open to tribal and non-tribal youngsters alike; at present, all students are Native, though not all are Ute—some are Navajo or members of other tribes.

KCA’s current building, a temporary modular building once owned by the U.S. Army, will be a tight fit for the projected student population over the coming years. There are plans to bring in an adjoining modular unit to house grades three through five. Discussions are underway with nonprofit organizations and architects about adding a middle school, but the main focus this year is to ensure that the elementary school thrives.

The school’s vision is straightforward. Kwiyagat Community Academy wants its graduates to have a “strong grounding in Nuchiu culture and language while incorporating modern perspectives as contributing members of the Ute Mountain Ute community.”

KCA, in essence, is taking the precise opposite approach of the infamous American Indian boarding schools that, under the federal government’s auspices from 1819 until the 1970s, sought to assimilate Native children. At those boarding schools, Indigenous names were replaced with western names. Cultural signifiers were disallowed. Native languages were forbidden. Many church-run schools, operated within the federal system, were found to have looked the other way rather than confront physical and sexual abuse. Some students died.

Instead, KCA intends to reinforce cultural attributes. Students participate in 40 minutes of cultural lessons daily, whether learning words or studying plants that are integral to Native culture. The existence of the school in the community and on tribal property means it’s much easier to invite community members to talk with students about their work or their role in the tribe.

Not one student at KCA would qualify for English Language Learner services because English is the primary language at home, says Porter. So the school is working to keep the Ute language alive while also making sure that English skills advance.

“I was subbing for kindergarten not too long ago and I said, ‘okay, let’s start counting,’” says King-Washington, the board president, a longtime teacher. “And they started counting in Ute and I said, ‘that’s good, but you need to count in English, too.’”

The school is not intended to “shield” students from the outside world, says Porter: “The students are going to have to be able to flourish outside the tribe.” He has held a variety of principalships and other education-related jobs in southwestern Colorado, and worked for years in the Montezuma-Cortez School District. His assignments included time as the district’s expulsion officer and as district liaison to Native parents. During his work with Cortez schools, he developed friendships with many students and families from the Ute Mountain Ute Reservation.

Kwiyagat Community Academy Principal Danny Porter and first-grade students enjoy some free time as a school day comes to a close.

The cultural divide from Towaoc to Cortez, said Porter, is real. As an example, Porter cites cases when tribal students attending Cortez schools were teased for the tribal tradition of cutting their long hair (both boys and girls) following a death in the family. At KCA, newly shorn locks might simply prompt a respectful question of, who passed?

“We don’t want to let this community down,” said Porter, who is white. “And that’s why everybody is working so hard. I think a lot of people realize the injustice that has been done. There’s a real danger of an ‘equity trap,’ of thinking we’re going to be the great white hope—that we’re going to save everything. That’s not what this is about. But most people can solve their problems if you give them the tools to do it, I really believe that.”

Kwiyagat Community Academy is authorized by the Colorado Charter School Institute (CSI). The Montezuma-Cortez School District agreed to waive its own authority to approve charter schools within its boundaries in order to allow the school to work with CSI.

CSI Executive Director Terry Croy Lewis, PhD believes that teaching Ute culture can work hand in hand with academics.

“I don’t think they are mutually exclusive,” said Lewis. “I think you can have academic success that meets state standards and in addition meets their mission, which is to ensure that they come through school knowledgeable about the [Ute] culture and that they can speak the [Ute] language.”

Lewis embraces the state’s multipronged accountability system, but she also believes that a new tool is needed to measure “mission-specific” goals such as those at KCA.

Test scores among Native students, and Ute Mountain Ute students in particular, indicate that their educational needs historically haven’t been met. From its own “Report on the Progress of American Indian Students,” the Cortez school district reported in October 2021 that 12% of Indigenous students in grades three through five met or exceeded state standards in language arts. That compared with 41% among students not affiliated with a tribe. In mathematics (using data from the 2018-19 school year; the 2019-20 Ute student population was too small to disaggregate), 3% of students met or exceed state standards compared to 23% of non-tribal students.

To Porter, good teaching starts with providing the right environment. The school opened in one room (kindergarten and first grade) in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic. That configuration was not a recipe for calm. First-grade students had little experience with coming to school, because the pandemic had kept them at home for online learning during kindergarten.

This year, the school has individual classrooms for kindergarten, first grade and second grade. Behavior has improved and Porter says students demonstrated “solid” academic growth within the 2021-22 school year.

Porter also cites more subjective data, such as the “relationship capital” that the school is building by becoming a resource to the community. “We are being approached from people who want things done. The school is developing ‘street cred’ by becoming an ally for those trying to build up the community,” says Porter.

Lopez, the kindergarten teacher, has a daughter who is too old for KCA and goes to school in Cortez. But a son is in second grade and attends the school, and uses Ute languages and phrases. Lopez says she has good relationships with all the parents of her students, a fact that is possible with the close proximity and regular presence of those parents. “That’s what makes our bond stronger,” she says.

Lopez and her kindergarten students.

But student absenteeism is a chronic issue—something Porter calls their “biggest challenge.” The school mailed out letters to 32 students and their families who had missed more than five days of classes so far this year. (That’s two-thirds of the student body.) One reason why: When there is a death or an illness in a Ute family, school takes a backseat to family relationships.

“We can’t teach kids when they’re not here,” says Porter.

Staffing is also a challenge. Porter wants a mix of Ute and non-Ute teachers on staff. Ideally, tribal members or other Indigenous teachers would be the majority of faculty; currently, one of the three full-time KCA teachers is Native, as are all of the substitute teachers and half of the paraprofessionals.

Lopez needed an emergency authorization from the Colorado Department of Education and is pursuing her teaching degree online through Western Governors University. Porter approached Lopez, who is Native, with the idea that she consider teaching. Getting her hired took three months to navigate both the state’s emergency authorization licensing process and the tribe’s paper-based workflow and procedures. “It’s quite a struggle,” says Porter.

The long-term challenges of stable, consistent staffing at the school are concerning to Mark Wing, a program manager for the tribe’s behavioral health office. Wing, a Ute tribal member who grew up in Towaoc and graduated from high school in Cortez, supports KCA and the fact that it eliminates the time-consuming commute to Cortez. But he is nervous that the remote location, combined with the modest teacher salaries that the school can afford, won’t be enough to attract the necessary talent.

“The teachers that are working here now—how long are they committed to be here? Do we have a backup plan to replace these individuals in case something happens?” said Wing. “Are we going to find staff to staff these buildings and these classrooms? Because, you know, you’re going to have to pay high dollar to get these people—teachers, counselors, therapists, you know, to serve all these kids’ needs.”

Wing would like the community to develop plans to train its own teachers and other necessary staff, especially as the school adds grades or expands to middle and high school.

At this stage, in its infancy, KCA purchases a variety of support services through its contract with CSI. In addition, consultants are helping KCA with financial management, applying for grants and planning.

Kwiyagat Community Academy first-grade students head out to the playground for some free time.

For Classia Hammond, a tribal member who lives in Towaoc, the ease of visiting with teachers is critical. Hammond has older children in Cortez schools and also has custody of two nephews, one in kindergarten and one in first grade at KCA.

“The teachers are very nice and I can meet with them one on one,” she said.

Hammond said she has been impressed with the efforts of KCA teachers to connect with her nephews and she likes the school “because they get to know their own heritage, their language and their history.”

To Porter, that’s key.

“I want students to be able to stand up in front of a crowd and say, ‘here’s who I am, here’s what I believe, and here’s why I believe it’—and to be able to do it in writing or through the spoken word,” he says.

The simple existence of KCA, says board president King-Washington, “changes the dynamics, changes the focus” of the community.

Parents “are there every day. They’re bringing their kids and we hear parents talking to other parents,” she says. “The school and the community, now they’re interwoven.”