Photo from DepositPhotos.com

Photo from DepositPhotos.com

Here’s the short answer: nobody really knows yet.

Definitive research on marijuana and health disparities is still lacking. Often, so few people are included as subjects in the few research studies or surveys that do exist that the results are too small to generate significant results by race.

A handful of surveys and studies have found differences in how young people of differing backgrounds—namely along race, ethnicity and sexual orientation—are affected by some aspects of marijuana’s recent legal proliferation in Colorado. Then again, other data point the other way.

A study presented at this year’s annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies found that in 2013 and 2014, one in six children hospitalized for lung inflammation—which can be caused by secondhand smoke—carried traces of THC, the psychoactive ingredient in marijuana, in their bloodstream. The study found that non-white children were more likely than white children to be affected.

Researchers don’t know if low-level exposure caused by secondhand smoke has negative effects, said Karen Wilson, MD, MPH, who led the research at the University of Colorado.

The sample of 43 children tested was too small to divide by race or ethnicity, so researchers grouped black, Hispanic and multiracial children together and compared them to the white children in the study. In general, tobacco smoke exposure disproportionately affects low-income and minority youth, she said. The fact that smoking marijuana in public is illegal could put children who live in multi-unit or less spacious housing more at risk if an adult decides to smoke indoors.

If a parent wants to smoke marijuana at home, “and you don’t have a house with a large backyard, you’re going to be doing it in front of your children,” Dr. Wilson said.

Another study found no differences in marijuana use of parents of different backgrounds. The 2014-15 Child Health Survey conducted by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE) asked black, white, Hispanic and multiracial parents whether they had used marijuana or marijuana products in the last 30 days or kept any in the house. The survey found no statistically significant differences.

Other data suggest negative social effects of marijuana have been slowest to disappear for young people of color.

Marijuana possession and use remains illegal for anyone under 21. One of advocates’ goals of legalizing recreational marijuana is to stem the flow of people of color into the criminal justice system for low-level drug offenses.

Instead, analysis by the Colorado Department of Public Safety found marijuana arrests of young people of color increased following legalization, while arrests of white youth decreased. From 2012 to 2014, 29 percent more Hispanic youth and 58 percent more black youth were arrested in Colorado for marijuana offenses, including possession, compared to 8 percent fewer white youth.

“We saw this coming,” said Art Way, senior director at the Colorado chapter of the Drug Policy Alliance, a pro-legalization advocacy group. During the implementation of recreational marijuana legalization, the Alliance negotiated increased opportunities for young people arrested for marijuana to be diverted away from jail to educational programs and have their records expunged. It’s hard to find data on how often young people are sent to these programs instead of jail, Way said, and it’s still too early to draw conclusions about how legal marijuana affects young people of color, public health and safety.

Marijuana usage among the young correlates to health problems, in addition to legal problems. A review of literature by researchers at CDPHE found a significant association between marijuana use in young adults and adolescents and health problems, such as mental illness, psychotic symptoms and future drug addiction; and social problems such as poor academic performance and dropping out of school.

Niko Cunningham discusses health risks like these with the youth he works with at human services organization Servicios de La Raza (a past Trust grantee) as a substance abuse coordinator. Young people don’t recognize the negative effect marijuana could have on their brain development, Cunningham said, as “youth struggle to see their lives past the weekend, let alone decades into adulthood where these negative issues are perceived to occur.”

Yet regular marijuana users tell him it helps them cope with life, Cunningham said. He points to marijuana use as a way young people from communities that stigmatize mental illness self-medicate rather than seek counseling.

The growing number of youth of color arrested for marijuana possession is “nothing new to us,” Cunningham said. People of color are already disproportionately represented in the criminal justice system. While law enforcement might be more lenient on a white teen using marijuana, considering him or her just “a kid out having fun,” Cunningham says he believes a young person of color with marijuana is likely to be treated more harshly.

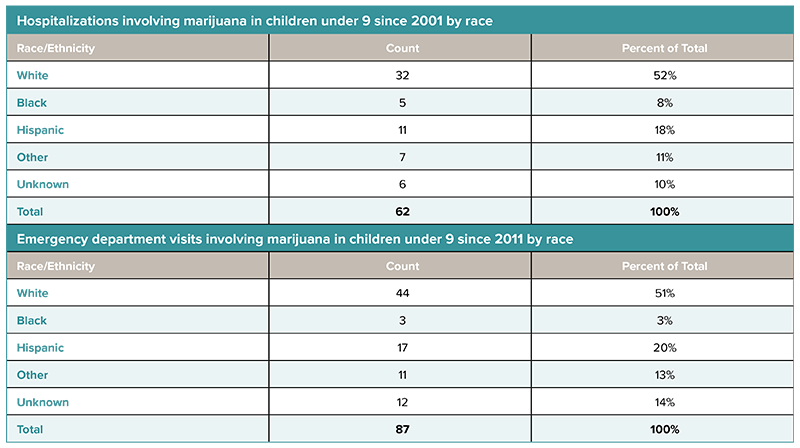

One indicator of the effect of legal marijuana on kids is the number of children hospitalized or sent to the emergency room for unwittingly ingesting marijuana products.

Since retail marijuana was legalized, the rate of hospitalizations due to possible marijuana exposure for children of all racial and ethnic backgrounds has more than tripled—to 26.4 per 100,000 in 2014 from 7.6 per 100,000 between 2010 and 2013. CDPHE research shows the most hospitalizations occurred in Adams, Denver and El Paso counties.

Looking at the numbers by race roughly mirrors the state’s demographic breakdown and doesn’t show a definitive difference.

Source: Colorado Hospital Association, via the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment

How often are children themselves electing to use marijuana? Colorado middle and high schoolers use marijuana at the same rate as the national average, according to the 2015 Healthy Kids Colorado Survey. That report did reveal notable disparities across several parameters, though.

The survey found that within the state, young people in Colorado use marijuana at different rates depending on where they live. Usage was highest in Denver and mountainous counties in the middle of the state, such as Grand, Eagle and Pitkin counties, along with Pueblo and Colorado’s southwestern counties such as La Plata, Montezuma and San Juan counties.

Sexual orientation, gender identification and racial or ethnic background comprise other disparities in usage, according to the survey.

Approximately a third or more youth who identified as bisexual, homosexual or transgender reported using marijuana, while a fifth of straight youth did. Youth of color reported trying marijuana before age 13 more frequently than white and Asian youth. That included 28 percent of multiracial youth, 27 percent of Pacific Islanders, 24 percent of Hispanics, 23 percent of blacks, 20 percent of American Indians, 20 percent of whites and 10 percent of Asians.

We might learn more about possible social disparities and marijuana in a few years. Many researchers have submitted proposals to CDPHE for part of over $2 million in marijuana taxes slated to fund new research, Chief of Environmental Epidemiology Mike Van Dyke said. Reviewers will give priority to studies on marijuana’s effect on adolescents, mothers and the LGBT community. It’s important to start to fill in gaps in knowledge on ethnic and racial disparities and marijuana, Van Dyke said: “That’s definitely on our agenda to study with these research grants.”