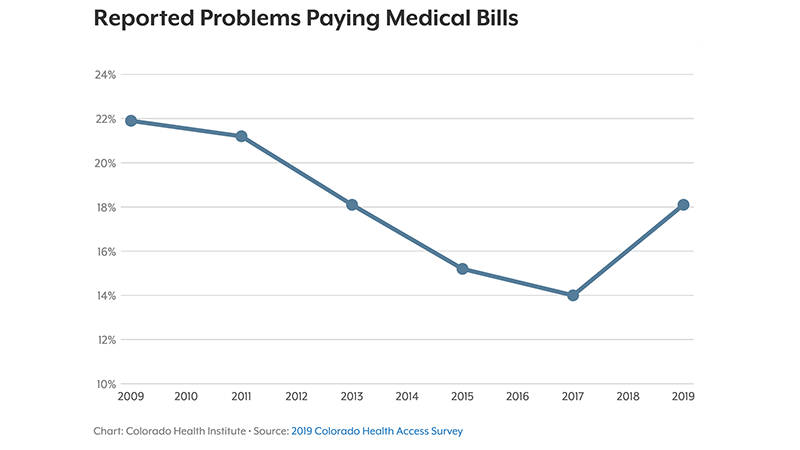

The 2019 Colorado Health Access Survey found that the number of Coloradans who reported problems paying medical bills has risen since the 2017 iteration of the study. (Source)

The 2019 Colorado Health Access Survey found that the number of Coloradans who reported problems paying medical bills has risen since the 2017 iteration of the study. (Source)

Currently, 93.5% of Coloradans have health care coverage—a rate that has stayed more or less consistent since 2015 after full implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

But that statistic doesn’t reveal the whole story about health care access and affordability in Colorado.

According to results from the Colorado Health Institute’s 2019 iteration of the Colorado Health Access Survey (CHAS), there are several worrisome signals that even in the midst of historically low uninsured rates, health care is becoming increasingly unaffordable and unattainable for many Coloradans.

The low uninsured rate “seems to be masking some underlying dynamics within the insurance market,” said Jeff Bontrager, director of research and evaluation at the Colorado Health Institute and principal investigator on the 2019 CHAS.

The CHAS, conducted every other year since 2009 with funding from The Colorado Trust (and, this year, other funders as well), polls 10,000 randomly selected households across the state with the goal of understanding Coloradans’ perspectives about their health and health care experiences; and then using that information to help inform policy decisions and approaches to addressing barriers.

In the 2019 report, released in September and titled Progress in Peril, there are several findings that suggest the beginning of regressive trends in Coloradan’s health and health care status.

For one, 89.6% of uninsured Coloradans reported that cost was the primary reason for their lack of coverage, said Bontrager. This is the highest percentage for this question that the CHAS has recorded since data collection started a decade ago.

Also of concern: 18.1% of Coloradans reported difficulties paying medical bills in the past year, the highest percentage since before major provisions of the ACA took effect in 2014. On top of that, about 30% of residents reported being surprised by a medical bill that they thought would be covered by insurance in the past year.

Other worrisome findings include:

Of note, the definition of “churn” was expanded in 2019 to include people who gained coverage. Though it’s possible the rise in churn could be due to the expanded definition, said Bontrager, he suspects the increase is due to a combination of factors. These include people losing Medicaid eligibility as the economy improved, as well as people not re-enrolling in Medicaid out of fears sparked by immigration policies enacted by the Trump administration.

“We think that churn can really impact someone’s continuity of the care that they’re getting,” Bontrager said.

The survey examined health-related issues outside of health care, too. Nearly 7% of Coloradans reported housing instability and 9.6% of Coloradans ate less than they felt they should because they didn’t have enough money for food in the past 12 months. These data—pulled from a new set of questions added to the CHAS in 2019 that address some key social determinants of health—are concerning, said Bontrager, because they represent a “relatively large portion of the population who, even during a good economy, is reporting problems with housing and with food insecurity.”

Yet amidst the concerning results were positive findings, like the fact that more residents are using health care services than in previous years. About 81.1% of Coloradans saw a general practitioner at least once in the past year, the report found, compared to 70.9% in 2017. Also, 73.6% of Coloradans visited a dentist, a significant increase from the 2017 rate of 66.4%, which had held steady for the past decade.

Overall, “a lot of the findings in my mind can be seen as like a glass-half-full, glass-half-empty,” said Bontrager. One example is data on behavioral health, which showed a nearly two-fold increase since 2017 in the number and percentage of Coloradans who indicated they had not received needed mental health care or needed substance-use disorder care in the past 12 months.

From a glass-half-full perspective, such increases could be explained by greater societal awareness of mental health that, in turn, helps people recognize they have an issue needing treatment, said Bontrager. But with a glass-half-empty mindset, “that increased demand isn’t necessarily translating into more people actually getting the services,” he added.

The 2019 CHAS allowed respondents to complete the survey online, versus the phone-based survey used in previous iterations. Bontrager notes respondents may have been more forthcoming online, which could also explain changes in some data.

The Colorado Health Institute is still crunching the data set and plans to release additional results at their annual health care conference this December, including a more in-depth analysis of which segments of the population may be experiencing inequities in health care access, affordability and more.