Alex and Kayla Koehler (top l. to r.) hand coloring books to their children Emma (center) and Damien (bottom r.) at the Mean Street Ministry shelter in Lakewood, Colo. March 2018. Photos by Joe Mahoney / Special to The Colorado Trust

Alex and Kayla Koehler (top l. to r.) hand coloring books to their children Emma (center) and Damien (bottom r.) at the Mean Street Ministry shelter in Lakewood, Colo. March 2018. Photos by Joe Mahoney / Special to The Colorado Trust

On a cold night in March, near a weather-beaten trailer park in the Denver suburb of Lakewood, Cody Teague, Shannon White and their two children settled in at the Mean Street Ministry homeless shelter, grateful for its warmth and safety, but uneasy about their future.

The family had weathered many difficult months after arriving in Colorado the previous fall. Their plan was to make a fresh start after a Wyoming machine plant where Teague worked shut its doors.

“Denver was the closest big city and that’s where we headed,” said White, 32, seated on a folding chair inside the school gymnasium rented by the shelter, surrounded by tents where nine families would sleep that night.

But Denver, with its thriving economy, brought longer odds than the couple anticipated. Jobs for Teague, an industrial mechanic, were hard to find. Housing prices were unaffordable and the family soon found itself low on cash and homeless, sleeping in their car or camping in out-of-the-way places.

The winter chill thrust the family into Denver’s tangled web of day and night shelters and eventually into a shabby motel on Colfax Avenue. That’s where Mean Street’s executive director Rev. James Fry discovered the family last December during one of his twice-weekly “street ministries” to deliver food and spiritual sustenance to people living in Colfax motels.

“This sure isn’t what we expected. If not for Mean Street, we wouldn’t have made it this far,” said White, her arms wrapped around her daughter McKenzie, a 2-year-old toddler with blond curls and blue eyes. The couple’s 5-year-old son Peyton played nearby with the children of other families who are homeless, while Teague helped shelter staff prepare an evening meal of spaghetti and meatballs.

McKenzie and Peyton Teague (l. to r.) play inside the Mean Street Ministry shelter while their parents help prepare meals and arrange sleeping spots for the night. March 2018.

The White-Teague family and others at Mean Street Ministry are the faces of suburban poverty. They reflect the growing population of low-income people now living in the nation’s suburbs, where poverty has risen more sharply than in urban or rural areas. Between 2000 and 2015, while poverty grew by roughly 20 percent in large urban cities, including Denver, it grew at least twice that fast in all metropolitan suburbs, reaching historic highs after the Great Recession. In the Denver metro suburbs, annual poverty growth rates started to ease slightly in 2014, ahead of national growth rates, but they remain substantially higher than in 2000.

In the four counties bordering Denver—Adams, Arapahoe, Douglas and Jefferson—the combined number of people living in poverty more than doubled between 2000 and 2014, rising from 92,707 to 187,455, according to U.S. Census numbers. During the same period, Denver County’s population living in poverty grew by 42 percent, from 72,609 people to 103,412.

“Americans think of suburbs as prosperous areas that are relatively free from poverty and unemployment,” said Scott Allard, PhD, professor of social policy at the University of Washington and author of the 2017 book Places in Need: The Changing Geography of Poverty. “But it’s a very common reality across the suburban landscape that suburbs are becoming poorer.”

There are many reasons, including lower-income people being priced out of vibrant, once affordable cities like Denver, where housing prices have doubled in the past eight years. But the most important reason, Allard said, is the change in labor market opportunities. Good-paying jobs requiring advanced training are disappearing from the suburbs, leaving lower-wage, lower-skill jobs that don’t lift people out of poverty.

“It’s the reverse of what happened in the 1970s and 1980s when a lot of people left the cities for opportunities in the suburbs,” Allard said.

The shifting geography of poverty has left many communities scrambling to find solutions for how to serve the growing population of people struggling to make ends meet—many of whom need permanent housing, health care, better jobs, good schools and, for those without vehicles, transportation.

“We know our poverty and homeless challenges are greater than they ever have been,” said Lynnae Flora, deputy director of the Jefferson County Department of Human Services, which created an office dedicated to helping homeless populations and developed a public-private partnership focused on breaking the cycle of poverty.

But many suburban cities and local communities are not prepared to handle their growing populations living in poverty. Experts believe that the framework built over several decades in Denver and other large U.S. cities to assist people with low incomes in denser urban areas does not fit the rapidly changing suburban geography, where people and services are scattered over great distances.

Across the country, suburban areas have “less infrastructure to support social services that support the populations in need,” said Harvard University health researcher Alina Schnake-Mall, ScD, MPH, citing one social determinant of health in particular—mobility: “The lack of adequate transportation in a sprawling county becomes a barrier to accessing food, medical and other services.”

In the long run, experts say, limited access to transit and networks of social services also makes it harder for people to connect to jobs and other opportunities that can help get them out of poverty.

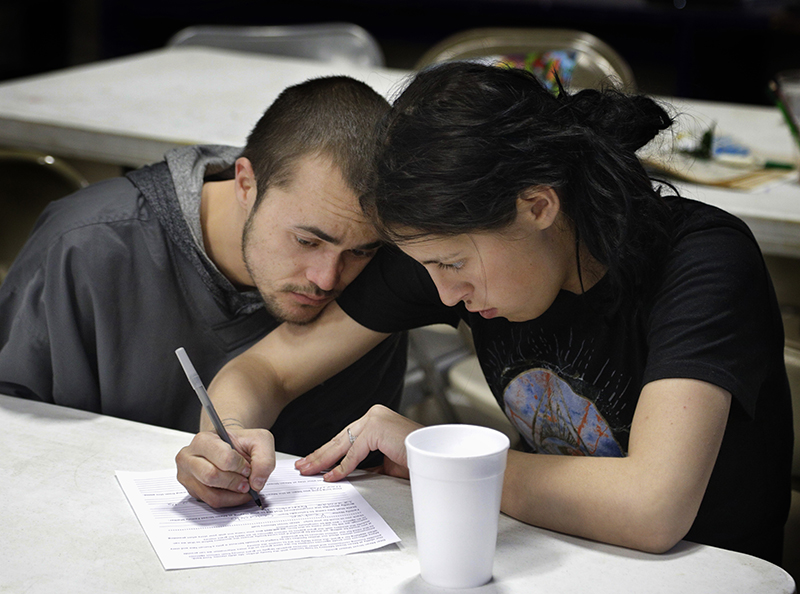

Alex and Kayla Koehler at Mean Street Ministry shelter. March 2018.

Alex and Kayla Koehler and their two children, Damien, 4, and Emma, 1 year old, ended up at Mean Street Ministry last January after losing their apartment in another Colorado county. The family had no savings, no car and no relatives in the area.

“The shelter is for the children, not for us,” said Kayla Koehler. “If it were just us, we might sleep on the streets.” Koehler said her daughter has been sickly since birth and needs to be in a more stable environment and under the regular care of a physician.

Koehler’s job doing market research was at a mall near Golden, 10 miles from the shelter. But getting to and from her job, to the physician in Golden and to pick up medication was difficult.

“Depending on where we are, I might find a bus to work. Otherwise I walk all the way,” Koehler said. “I’ve lost 20 pounds and I’ve gotten sick.”

Meanwhile, since the shelter closes at 7 a.m., Alex Koehler cared for the children during the day, walking around Lakewood, stopping in parks and libraries, and looking for places to rest without being bothered. (Lakewood anti-trespassing ordinances bar individuals from spending hours at a time in parks, libraries and other public spaces.)

“Getting to the doctor, I try to find someone with a car to take us,” Kayla Koehler said.

Denver’s four adjacent counties are at least five times larger geographically than Denver County. Jefferson County, the largest in population but the smallest geographically of the four, measures 774 square miles compared with Denver County’s 155 square miles. A regional rail system connecting Denver and its suburbs is under development, but local public transportation within the counties with sufficient routes and connections remains elusive.

“The suburbs were never equipped for this, and still aren’t,” said Rev. Fry, whose Mean Street Ministry nonprofit organization provided the only overnight emergency family shelter in Jefferson County last winter. If space was available and families passed a background check, the shelter took them in immediately. The few other overnight shelters in the sprawling county are smaller, accept families via a lottery system or have wait lists, and separate parents by gender.

Throughout the metro area, the need for shelters and affordable housing is dire, said Don May, executive director of the Adams County Housing Authority.

“Housing is the biggest and most critical challenge for homeless people and for suburbs trying to help,” May said. “If a person doesn’t have a place to live, they can’t focus on other needs, including health. Their well-being is impacted totally.”

In Adams County, where approximately 58,870 people lived in poverty in 2017, the housing need is so great that last year, in a matter of days, the county received more than 4,000 applications for 150 federal government housing vouchers, May said.

But given the Denver metro area’s sizzling housing market, many places no longer accept the rental vouchers, said May. That includes some of the motels along Colfax Avenue running through Jefferson County and the City of Lakewood.

“We don’t take vouchers anymore,” said Kimberly Kim, working the front desk at the Homestead Motel on West Colfax in Lakewood. “They don’t pay enough. They paid $200 per week not long ago, but our least expensive one-bedroom is $320 per week.”

On that night in March, all of the families at Mean Street were “working poor,” defined by the Bureau of Labor Statistics as people living below the federal poverty line who spent at least half the year either working or looking for employment. Most had a car.

Despite the difficulties navigating a vast county and trying to find jobs, housing and services, those present said they were drawn to the suburbs for their safer streets, good schools and family-friendly residents. Some said they’d had belongings stolen in Denver and were concerned for their children’s safety there.

Todd Graber, Mean Street’s manager, said 2014 was the year he noticed more families than homeless men coming to the shelter for help. “Many of them had jobs and vehicles but they didn’t want to go to Aurora or downtown Denver,” Graber said. “They had kids and didn’t feel safe over there.”

Cody Teague and Shannon White at a park in Lakewood, a frequent destination for the family on Sundays so that their children can play outside. March 2018.

Cody Teague, 32, worked day-labor construction that took him to other counties or to the mountains, where he helped build houses. It’s temporary work and he sometimes spent an entire day’s wages on gas, food and essentials for the children. “On what I make, there’s nothing left to pay for rent,” he said. “It doesn’t take long to go through a tank of gas.”

One good-paying, permanent job offer in Denver was revoked, Teague said, after the company learned his address would be a homeless shelter—or the family truck—until he earned enough money to get an apartment. “I need a permanent job, but companies won’t hire people who are homeless,” he said.

While Teague worked, his wife sometimes volunteered at Mean Street’s day pantry and clothing bank, “so the children have a safe place to be.” Some days, she had no choice but to kill time on the streets. Still, while the suburbs are “definitely friendlier to families,” she said, they are at a disadvantage because they lack the services of many dense urban cities, like Denver, where she found the downtown more convenient for a family on foot to access food, buses and health care.

“The children have been sick on and off, more so than usual. When you’re homeless, you can’t eat like you used to,” said White. “There are constant disruptions. You get sick more often and you stay sick longer. Finding doctors to help poor families in the suburbs is impossible.” It’s easier to take the children to the Stout Street Clinic in downtown Denver because “the buses in and out of Denver are more frequent and the clinic serves poor families,” she said.

“When people experience displacement and other severe disruptions in their normal pattern of life, it can take a toll,” said Quinta Moore, MD, JD, a fellow in child health policy at the Baker Institute for Public Policy at Rice University in Houston. “The suburbs create additional challenges and stress for families. There’s not the same access to services, food pantries and other things in the suburbs that people come to rely on in urban areas.”

“Research has found there are important gaps in the availability of health care services in the suburbs,” where nearly 40 percent of the uninsured population live, said Schnake-Mall, a doctoral student at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

“It’s not barriers necessarily around there not being enough providers, but about there not being enough providers that accept uninsured or Medicaid patients,” Schnake-Mall said. Research also suggests that “physicians can perhaps be slightly less likely to accept Medicaid patients in suburban areas,” she added.

Debunking the Myth

The number of people living in poverty in the suburbs has grown steadily for more than two decades. Yet, few seem to have noticed. In many suburbs, poverty remains hidden in part because the physical landscape makes seeing poverty more difficult. In some suburbs, residents are not ready to associate poverty with their own communities.

“Many people think there is no poverty or homelessness in Jefferson County,” said Laurie Walowitz, director of program services for the nonprofit Action Center in Lakewood. “But that’s not the case. I live it every day.”

Demand for the Action Center’s services, which include counseling, food and other basic assistance, has jumped 40 percent since the beginning of 2008. The nonprofit recently closed its overnight shelter, due to a drop in donations.

In Lakewood, where approximately 18,000 people had income at or below the federal poverty level in 2017, the presence of people struggling to get by went unnoticed among the general population until their numbers reached a critical mass, said Rev. Fry.

“We used to send our homeless downtown,” meaning Denver, said Fry. “But now there are too many to ignore. Residents and business people are literally finding poor people in their alleyways. This is no longer something that can be shoved into downtown Denver.”

In some areas of the county, including the tiny hamlet of Edgewater along Denver’s western boundary, and Golden, at the base of the Rockies, poverty has reached astonishing numbers, well above the state and national rates.

“People don’t think of Golden as a place where poverty exists. It’s not something you notice,” said Karen Groves, with the Jefferson County League of Women Voters. “Golden is a growing area. There are apartments going up.”

The hidden nature of poverty is one of many reasons solutions have been in short supply, said Allard, who is also a senior nonresident fellow at the Brookings Institution Metropolitan Policy Program.

“Suburbs are still not viewed as places that need increased social services, in part because the poverty is spread out, it’s less visible,” Allard said. “It might be clustered in some cities, but in places that simply aren’t as visible, and due to the disconnection, their residents have poor access to amenities and community services. It’s one of the reasons suburbs have been unprepared to deal with the needs.”

Other reasons include lack of political will and limited resources to serve the poor, Allard said.

“The lion’s share of government resources get funneled to cities and nonprofits that operate within cities,” Allard said. “That’s where we expect poverty to be found. When it appears elsewhere, the organizations and funding simply aren’t around.”

“This may be driven by many considerations, but fundamentally reflects a lack of political will to engage poverty problems in our midst,” Allard added. “It also is common to think of poverty as being an element from the outside and therefore not part of a suburban community.”

Increases in poverty have been across all racial and ethnic groups in the suburbs, “with particularly large increases among Hispanic suburban residents in recent years,” Allard noted. “Nevertheless, white non-Hispanics still compose the largest share of the poor in most suburbs,” he said.

Out in the Open

Food pantries are among the places where poverty is more visible in the suburbs. One day around the 2017 holidays, the Arvada food bank, Community Table, ran out of food, said Mark Stratford, director of food programs. “I went outside and saw the line wrapped around the building. I knew we weren’t going to have enough food for everybody,” he said. The pantry closed early that day.

Community Table is the only fresh-food pantry in Jefferson County open five days a week without an appointment to anyone who needs food, Stratford said. It offers produce, meat, fish, milk as well as canned and packaged food.

From August 2014 to August 2018, the food bank saw a 17 percent increase in household visits in just one of its five food programs. “We’re not going to turn anyone away,” Stratford said. But that can mean running out of popular items like peanut butter and canned fruit, or having to close early on occasion.

“The thing that surprises me is the number of transitional families coming through. We’re seeing a 10 percent increase in new families every month,” Stratford said.

Nichole Mitchell said she visits the Arvada pantry twice a month. “If not for the churches and the food banks, I don’t know what we would do,” said Mitchell, after picking up groceries for her husband and daughter. “It’s the only way our family can get by.”

The family returned to Jefferson County after working in South Dakota for a few years, only to find that “housing prices were so much higher than when we left,” said Mitchell. The family pays $1,000 a month to rent a cramped, two-bedroom apartment. “My husband works but it’s tough to make ends meet,” said Mitchell, adding that she is also looking for a job.

In the Arapahoe County city of Englewood, the Cornerstone Food Bank registered 13,645 client visits in 2017, a 41 percent increase from the 9,700 client visits in 2008, said executive director Naomi Rubin. The food bank, open three hours a week near the south Broadway corridor, serves mostly working families, including “nicely dressed people who are underemployed,” she said.

Rubin told the story of one family living in a middle-class neighborhood. The husband’s business went bankrupt, the family was “up to their eyeballs in debt” and became desperate for food, she said.

“Poverty in the suburbs in some areas is invisible. Neighbors are unaware that they live next to a family in poverty who can’t even afford groceries,” said Rubin, who discreetly delivered food to the family after learning of their plight.

Increased suburban poverty is also visible in the Jefferson County public schools, where 2,825 students were identified as being homeless in the 2016-17 school year, including 314 who were unaccompanied by a parent or guardian, said Rebecca Dunn, coordinator of the school system’s Community and Family Connections program. “I can say that we have had a steady increase over the last four school years,” she said.

Around 27,000 children whose families earn 130 percent of the federal poverty level or less were deemed eligible for the free or reduced price meals in the 2017-18 school year.

The Connections program is designed to help students living with friends, relatives, in motels, cars and other situations that are not “fixed, regular and adequate,” said Dunn. Partnering with other agencies, the program provides homeless children with clothing, hygiene products and, for those outside the attendance areas, bus passes.

Seventy-five percent of children deemed homeless in Jefferson County Public Schools are doubled up with family or friends, or live in low-rent motels, said Dunn. The other 25 percent live in shelters, cars, RV parks and other precarious situations.

Churches Filling the Gap

Poverty has even become noticeable in the bucolic mountain village of Evergreen where the annual median household income exceeds $95,000 among its 9,000 residents. “A few years ago, families walking alongside the road, or approaching customers at the Walmart, were things you didn’t see at all,” said Groves. “Now you do.”

Evergreen’s Christian and Jewish faith communities came together in 2015 after people were found camped in a church meadow where mountain lions and bears like to roam. “We were worried that they might get attacked or start a big fire,” said Rev. Michael McManus, pastor of the Church of the Transfiguration, an episcopal church in Evergreen.

With help from Mean Street’s Reverend Fry, the churches and synagogue developed a cold-weather emergency shelter system. People with low-wage jobs have become its fastest growing population, McManus said: “Some work two or three jobs but they can’t make it.”

“The biggest issue here and everywhere is housing. If you’re poor or homeless, you can find food. We have food pantries in Evergreen,” McManus said. “The hard thing is housing.”

The Rock Church in the Douglas County city of Castle Rock saved Thanksgiving Day for Cody Teague and his family last year, after Teague desperately searched for a place where his family could give thanks and eat a hot meal together. Church members not only served the family a full Thanksgiving dinner, but also provided a three-night stay for them at a nearby motel. “First we had a Thanksgiving meal at the church and then they delivered more food to the motel,” said Teague. “It was unbelievable, more than we ever expected. We were so grateful.”

Cody Teague with his daughter McKenzie. March 2018.

Douglas County is the most affluent county in Colorado and among the wealthiest in the United States, with a median household income of $105,759 in 2016 dollars.

One could be forgiven for thinking poverty does not exist in this posh suburb. But in fact, the number of people living in poverty more than tripled between 2000 and 2017, from 3,355 to approximately 11,400—or from 1.7 percent to 3.4 percent of the total population.

The Rock’s outreach to the poor and homeless began in July 2016, after Pastor Mike Polhemus said he noticed that “some people were really struggling.” In partnership with Douglas County and area churches and using private donations, The Rock started serving free meals on Wednesday nights to anyone who would come—whether they were in need or financially well-off—in order not to single anyone out.

“They all sit at the same table together. They’re talking and interacting, so it’s a community, no separation. Everyone fits together,” said Polhemus, eager to educate outsiders about The Rock’s hospitality. “This isn’t just like a chintzy little meal. It’s like a full-course meal,” including salad and dessert, he said.

The Wednesday night meals, attended by 300 to 400 people, led to a partnership with other churches to open food and clothing banks and launch a round-robin winter emergency shelter system for homeless women and children.

When The Rock’s turn comes around on Saturday nights, church teams set up living stations with 45 cots, prepare dinner for shelter residents, and in the morning serve breakfast, pack the overnighters a lunch and give them cash cards for gasoline, the pastor said.

“Out of it, we’ve actually seen two families now that were homeless that have stabilized and are now in an apartment and have a home and have jobs and are off the streets,” Polhemus added.

Last November, The Rock collaborated with Douglas County and the ride-share company Lyft to launch a transportation service for single moms and elderly and ill people who need a ride to work, the grocery store, a health care provider or the shelter. “It’s a lifeline for people. They need to get around and we recognize that it’s a huge, growing need,” said Faye Estes, Douglas County mobility program manager.

In addition to helping people pay rent, mortgage and utility bills, The Rock gave used vehicles to three families. Polhemus estimated some $87,000 in church donations were spent last year to help people with a range of needs.

“I think the churches are just now getting an understanding that poverty and homelessness are things we need to actually address,” Polhemus said. “It’s something we could have done 10 years ago, but we’re starting to do it now. The more we do, the more we realize there is so much more to do.”

A Year Wiser?

As of September, it had been a year since Teague and his family arrived in Colorado filled with hope.

In recent months, they lost what little belongings they owned after they were late in paying for the storage unit where they had stowed their things.

When Mean Street closed for the season on March 31, the Koehlers and 14 other homeless families received vouchers for long-term rental housing, but the Teague-White family was not so lucky. Without a steady job, Teague was not able to show that he could earn a consistent paycheck and contribute to the rent, as required by the voucher.

The family headed to the mountains, where Teague helped a man build his home. The man gave the family permission to camp on his property.

They returned to Lakewood in time to enroll Peyton, now 6, in school. Meanwhile, White found a job at a Denver restaurant working 10 hours a day, six days a week. Teague continues to work temporary jobs while seeking permanent work and helping care for the children. The family rented a room in a Colfax Avenue motel, paying around $1,400 a month. (The average monthly rent for a one-bedroom apartment in Lakewood ranges from $1,238 to $1,387.)

The optimism the couple felt when they arrived in Colorado has faded as they struggle to make ends meet. “Tired,” is how White said she feels. “I don’t see my kids much, but I have to work. We’re one step from being homeless.” Still, “the children are happy,” she said.

Teague, now 33, no longer feels as hopeful as he once did. “I’ve been disappointed too many times,” he said. “Right now, I’m taking it one day at a time, one job at a time.”

As for Mean Street Ministry, which had rented its space from the New Life in Christ Church, Rev. Fry said he lost the contract to use the gymnasium during the coming winter.

“I plan to find another location for the shelter. We need the shelter,” Fry said. “In fact, we need a shelter all year-round.”