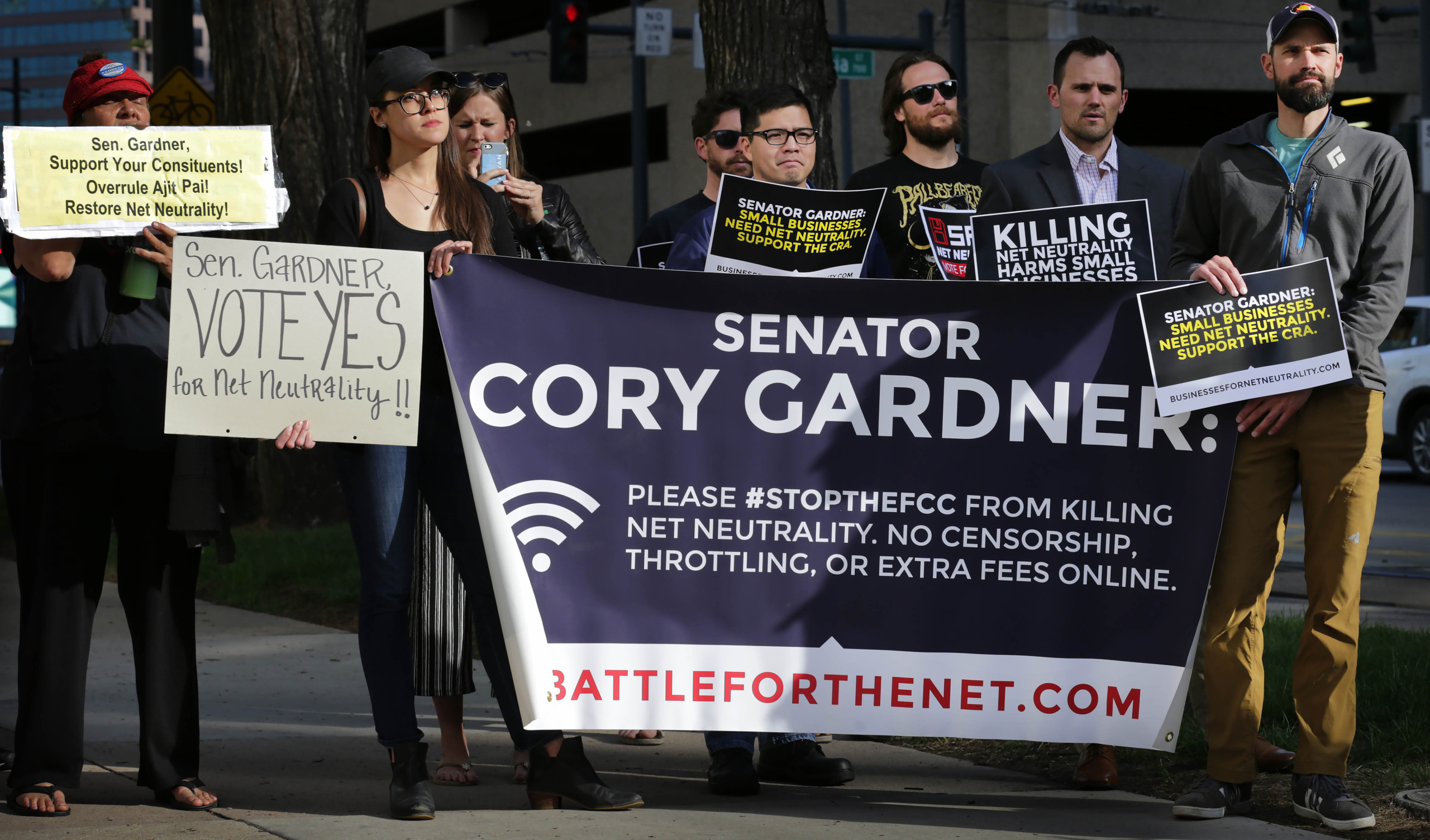

Net neutrality proponents held a rally outside Sen. Cory Gardner’s office in downtown Denver on May 14, 2018.

Photo by Joe Mahoney

Net neutrality proponents held a rally outside Sen. Cory Gardner’s office in downtown Denver on May 14, 2018.

Photo by Joe Mahoney

By Michael Booth

Colin Garfield’s transition from “regular IT guy” to “access activist” in Fort Collins in the past two years spans a number of eye-opening moments, but a few stand out.

Garfield had always felt the average internet consumer was vulnerable to corporate gamesmanship by monopoly or duopoly providers, from ever-ratcheting prices to crushing data caps. Then he heard from families in the Poudre School District who take their kids to McDonald’s for online homework—until as late as the fast food outlet stays open—because it’s the best place to get a fast, affordable internet connection.

“The average person doesn’t think of these scenarios in a city that is highly educated and fairly affluent,” Garfield said.

Carmen Scurato, vice president of policy and general counsel with the National Hispanic Media Coalition—a group that advocates for fair treatment and access in public communication—mentions the testimonial that struck her the hardest while touring the country to discuss net neutrality and public broadband access.

The coalition was listening to stories on Skid Row, the historic neighborhood on the edge of Los Angeles’s gentrifying downtown that remains a major homeless encampment. A homeless woman spoke up to say she had tried to make a doctor’s appointment with a phone call, and was told that practice only took appointments online through a patient portal.

The low-income consumer needs access to broadband, and their health care providers shouldn’t have to pay internet service providers (ISPs) more to deliver services to those consumers, said Scurato—a distinct possibility without net neutrality.

“When you have access to the internet, you can find jobs; you can connect with education institutions; it’s where kids go to do their homework; and it’s increasingly becoming the way you access your health care provider,” Scurato said.

“If you don’t have equitable access to the internet, you’re going to miss out on opportunities.”

A widening array of citizen activists, advocacy groups and politicians has coalesced in the past six months around net neutrality—the ideal that ISPs should not be able to charge different rates to content providers and websites, or “throttle” (meter, ration or slow down) traffic they don’t favor for either commercial or ideological reasons. Health care providers, for example, see how many vital medical records (often including large-size imaging files) and communications now travel online, and worry a greedy or unscrupulous ISP could demand that providers pay high fees to place or transmit information online.

Political and social activists fear higher fees or throttling by an ideological internet corporation could slow or stop the flow of information that fuels their movements. Facebook, for example, where many activists across all ideologies meet and communicate, is currently targeting Russian false fronts and “fake news”—yet corporate targets for content to filter, slow or even censor could easily change, with little to no recourse for consumers.

Net neutrality had been the law of the land in the U.S. from 2015 until last November, when a new Federal Communications Commission chairman appointed by the Trump administration announced the FCC would seek to reverse the rules. A 3-2 FCC board majority later voted formally to reject 2015 net neutrality protections, saying companies would fail to invest and innovate under too much regulation.

On May 16, the U.S. Senate passed a resolution by a 52-47 margin calling for a suspension of the net neutrality repeal, with three Republicans joining all Senate Democrats in support. The resolution is not expected to pass the House, nor to receive any support from President Trump. As of the date of this article’s publication, the FCC is set to end net neutrality on June 11.

Opponents of net neutrality have also argued the rules solved a nonexistent problem, as no corporations were publicly claiming a desire or intent to throttle the internet. Net neutrality activists scoff at that, offering lists of examples where providers have attempted to throttle content, or charge competitors or high-traffic content producers more.

Citizen groups have rallied in Colorado and across the country to restore net neutrality rules. Cities and counties—with Fort Collins among the largest—have voted to launch municipal broadband projects across Colorado, both to speed the arrival of faster broadband in remote areas and to protect net neutrality in their own community.

In March, more than 20 mayors, including two from Colorado, joined net neutrality pledges led by New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio. States including Colorado debated various legislative fixes for net neutrality, though even supporters are not sure those would stand a court challenge, given the cross-border nature of internet traffic and constitutional protections for interstate commerce.

The flourishing of citizen activism around internet freedom and opportunity has energized people like Garfield, who never saw himself as a public crusader.

“It’s waking up and realizing that decisions are being made for [citizens] without their input or control, and it’s finally scaring people what long-term damage can be done,” Garfield said.

For groups like the National Hispanic Media Coalition, Scurato said, communication of its ideas, plans and progress is now inseparable from the modern internet.

“So many movements that have started online have turned into national conversations on racism, sexual harassment,” Scurato said. “Black Lives Matter, #MeToo… so much of that is online, and if that equitable access doesn’t exist, these movements won’t continue to exist.”

More established activist groups are capitalizing on that grassroots energy to both push for state and local internet protections, and urge the federal courts or Congress to reverse the FCC decision.

“It’s very much about having equitable access to the internet,” said Caroline Fry of Colorado Common Cause, a left-leaning advocate for increased government accountability.

Fry cited particular concerns for rural Coloradans, who still have the highest percentage of residents without access to affordable or reliable high-speed broadband services. Many rural officials and economic development leaders liken the need for broadband to the need for basic electricity connections on the grid in the 1930s—an essential public service for all citizens.

“We operate under the premise that for Americans to be fully participating members of society, we need to be able to connect with each other and find out what’s going on in our communities,” Fry said. “That’s why we’re passionate about it.”

Fry and others noted that online connections have now become essential to urban and rural residents alike, in everything from business commerce, to job searches, to homework, to college applications, to farming, to tourism, to health care appointments and services.

A 2018 analysis by Pew Research Center found that 11 percent of U.S. adults still don’t use the internet—and that this divide is highly correlated with educational attainment and income level, two of the most significant social determinants of health.

“Roughly one-in-three adults with less than a high school education (35%) do not use the internet, but that share falls as the level of educational attainment increases. Adults from households earning less than $30,000 a year are far more likely than the most affluent adults to not use the internet,” Pew reported. Additionally, the research found that rural Americans are “more than twice as likely” as urbanite or suburbanites to never go online.

“Broadband and net neutrality essentially are health issues,” said Jessica Nguyen, community partnerships specialist for the Center for Health Progress in Denver. (The organization is a grantee of The Colorado Trust.) “They open up connections to education, communication, job prospects. It’s telemedicine, it’s telehealth, connecting with providers.

“There’s already a digital divide,” added Nguyen. “People with more money—and that’s closely associated with race, I’m afraid—have better access to the world.” Allowing service providers to charge certain web content creators more for higher speeds or better access would only widen that financial gulf, she said.

It is common already for carriers to charge consumers more for higher broadband speeds. The issue in net neutrality debates concerns ISPs charging the content providers—whether high-volume users like Netflix, vital services such as physicians, or a political site that is controversial—more than others for access to the delivery network.

Of the two primary worries of internet activists—blocking or throttling content based on ideology, and charging content creators more to see their websites load faster—some experts say the latter is far more realistic. Yet they are also leery of recent examples of large corporations allegedly steering content with ideology. Though Sinclair Broadcasting controls local TV stations instead of the internet, they are often raised as an example for allegedly dictating right-wing news content not just on air, but online.

But there’s been far more grumbling among ISPs, net neutrality supporters said, of the bandwidth taken up by popular content such as Spotify and Netflix.

“If you are Netflix and Spotify, you’re going to want a fast lane, and you’re going to be willing to pay almost any amount of money for it,” said Stephen Blum, president of Tellus Venture Associates in California, which specializes in helping communities develop new broadband. That’s where inequity for others comes in: “As an operator of a website that doesn’t have the fast lane to your audience, you’ll have to find other ways to make people aware of what you’re doing. It’s not Armageddon, but it’s not a good thing, either.”

The spirited debate over net neutrality since last fall has boosted local efforts in Colorado to secure citizen-controlled sources of broadband, through loopholes left by communications law. In 2005, Colorado prohibited local governments from building their own broadband networks, but let them reject that restriction if they held a local vote.

In the fall of 2017, 19 more cities and counties in Colorado voted for municipal broadband control, making it 116 altogether. Fort Collins (pop. 161,000) joined in a big way last November, voting to direct the City Council to create a locally controlled high-speed internet system from $150 million in bonds, with service to start between 2019 and 2021 for most customers.

The council and mayor have also committed to making the city-owned system net-neutral, with plans to write that into city laws as the system gets built. “It’s controlling your own destiny as a city, as a community,” said local activist Garfield.

The renewed push for “middle mile” and “last mile” improvements in broadband across Colorado could speed state efforts to guarantee fast access to 100 percent of rural Colorado by 2020. The most recent estimate said that about 23 percent of residents lacked access, or 125,00 to 160,000 households.

Many communities are drawing on state and federal funds to extend fiber optic cables into their service areas; some of those then deploy or partner with private ISPs to build wireless “last mile” service to homes and businesses.

Interest has picked up, said Nate Walowitz, regional broadband program director at Northwest Colorado Council of Governments, because underserved communities grew tired of waiting for private industry to complete the network. With new subsidy funds and new enthusiasm, the time is now, he said. Build-out efforts are at varying stages in Breckenridge, Meeker, Rangely, Red Cliff and Rio Blanco County.

Rural Colorado communities “know that if they let this opportunity go by, they’ve seen millennials grow up and leave and not come back, on top of trying to attract new population,” Walowitz said.

Discussions on net neutrality are rarely far behind the questions of the broadband build-out, he noted.

“Even in communities where the electorate tends to be more conservative, they clearly understand the value of having multiple provider options, and there’s an enormous sense of pride and independence in Colorado,” he said. “Many of these areas have lived with satellite providers who had caps on data plans, caps on speed, and an open, competitive internet—and access to that—is very valuable to them.”

Walowitz said he has urged the local governments he works with to adopt language similar to the state of Montana’s, which says ISPs with state contracts must honor net neutrality. A similar state-level proposal for Colorado this year died in a Republican-controlled legislative committee.

CenturyLink is a major ISP for much of Colorado, and in some rural parts of the state has little competition. The company said in a statement that it respects the rights of local governments to vote for citizen-controlled broadband efforts, but also wants to continue public-private partnerships CenturyLink has used in communities to speed up broadband build-out.

As for net neutrality, CenturyLink said this: “Consumers and businesses require a seamless and predictable internet experience. For that to happen, every email, application and video should not be subject to multiple state jurisdictions. From a policy standpoint, internet traffic is inherently interstate in nature and thus best handled at the federal level.”

On that, the activists agree: They want to protect net neutrality at the federal level. They are suing the FCC to reverse the decision, while also trying to build support in Congress to overrule the FCC legislatively.

“Our generation needs to have net neutrality if we’re going to have any chance of succeeding and making sure people have equal opportunities,” said Zach Amdursky, a Denver physician’s assistant who has helped organize local net neutrality support rallies. “Maybe they slow down anything with ‘#MeToo,’ or we can’t see other movements like women’s pay, or equality for the poor. The only way our generation gets anything done is through a hashtag.”