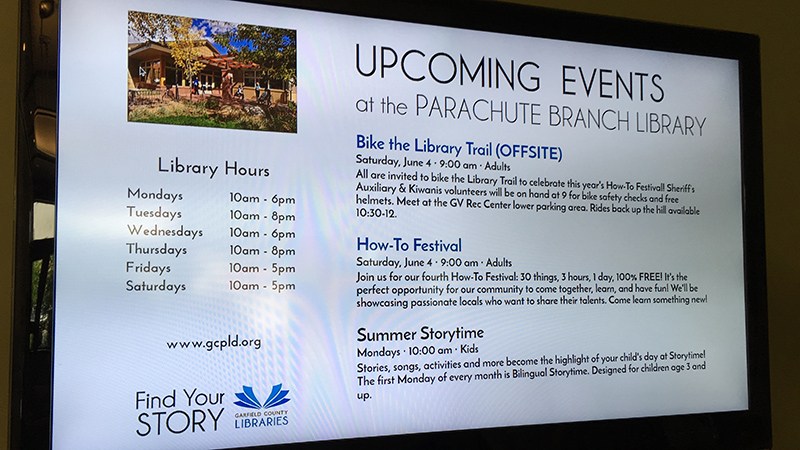

The public library in Parachute offers free programs and activities for the community. Photo by Kristin Jones

The public library in Parachute offers free programs and activities for the community. Photo by Kristin Jones

The town of Parachute sits along the I-70 corridor, roughly equidistant from the cities of Grand Junction and Glenwood Springs. A lot of the people who live in Parachute commute to one of those cities, or to nearby towns for work. The town is a bedroom community, a place where low-income people can afford to live, in a part of the state that’s dominated by the ebbs and flows of the oil and gas industry on the Western Slope, and the resort towns to the east.

About 38 percent of Parachute households make less than $25,000 a year, according to 2014 census data. The median income is $31,302, and the population is 33 percent Hispanic.

Up the hill from Parachute, on the south side of the highway, is Battlement Mesa, a residential and commercial development guarded by covenants and land-use regulations. It’s whiter and wealthier there; the median income is $64,948, and it’s 23 percent Hispanic.

The two communities share schools, roads, parks, a newly built public library, a grocery store and a highway exit.

Low-income families here experience a visible inequality in their daily lives. They may work in the service industry in Aspen; send their kids to school with others who can afford to go skiing in the winter and rafting in the summer; speak a different language than the dominant one; or struggle to afford the groceries on offer at the local store or the health insurance sold on the state exchange.

How does this inequality affect their health? Are low-income residents of Parachute better off than they would be in other places, because they have access to the same schools, libraries and roads as their wealthier neighbors? Or are they worse off, because they’re surrounded by things they can’t fully access?

Science doesn’t answer these questions. Health data can provide clues on things like infant mortality, birth weight, the prevalence of disease or the length of lives. But it rarely captures the quality of a life, or a person’s well-being.

In April, a national study by Stanford economist Raj Chetty and several colleagues made a groundbreaking effort to shed light on the relationship between income and life expectancy. The authors found a huge and growing discrepancy in the life spans of rich and poor in America. Men in the top 1 percent of earnings lived 14.6 years longer on average than the men in the bottom 1 percent; rich women lived 10.1 years longer than poor women.

They also found vast differences in longevity of low-income people depending on where they live. Even within just the boundaries of Colorado, there are stark differences, a New York Times visualization of the same research shows.

Life expectancy of a poor person living in the Pueblo area is about 77.5 years—almost six years less than a poor person living in the Glenwood Springs area, which for the purposes of this study includes the counties of Eagle and Garfield, where Parachute is.

The study doesn’t offer a reason for the differences in longevity. But it does analyze some of the correlations: for example, the percentage of poor people who smoke (20.4 percent in the Glenwood Springs area, 33.1 percent in the Pueblo area); the percentage who are immigrants (13.4 percent in Glenwood Springs and 3.8 percent in Pueblo—having a high immigrant population is generally protective to health, research has found); the median home value ($430,000 in Glenwood Springs, $120,000 in Pueblo); and local government spending per capita ($5,300 in Glenwood Springs and $2,400 in Pueblo).

The study found weaker correlations with the percentage of poor people in a region who are obese, how much they exercise and the college graduation rate. There was also no correlation between life expectancy among the poor in an area and per-capita Medicare spending, nor the percentage uninsured (there are fewer uninsured residents in the Pueblo area than the mountain resort corridor, where premium rates are precipitous).

Johnny Jasso pays $719 per month for a three-bedroom in Parachute, which he shares with his girlfriend and their three kids, and his girlfriend’s little sister. The kids who are old enough to go to school love it, and Jasso has been impressed with the teachers.

It’s not perfect: He wishes he could afford health insurance, and access health care. He wishes there were community bikes in town, so that kids who can’t afford bikes could take advantage of all the trails around here. He wishes the school week lasted all five days, instead of four, and that the kids didn’t have to go up the hill to Battlement Mesa.

“There’s definitely a sense of difference” between the two places, he says.

Jasso is also going to school himself, to be a substance abuse counselor, which can be a lot of work on top of parenting and a day job doing research for a law firm. He says he likes the small-town atmosphere in Parachute.

“I’ve always lived in a big city. Minneapolis, Denver, Houston, Austin. It’s a nice change of pace. You get to slow down,” he says. “Living around here is not as stressful. I don’t have to worry about being shot, being mugged.”

Jennifer Ludwig is the public health director in Eagle County, where life expectancies for low-income people look the very best in the state (even better than Garfield county), and are among the highest in the country, according to Chetty’s research.

Ludwig notes the strong investment from government and nonprofit sources in Eagle County that benefit low-income residents—for everything from education to roads, sidewalks and public transportation to affordable housing. There are also strong tobacco policies in the county, going further than state laws, to ban smoking even in many outdoor locations.

“What may improve health outcomes is the investment in the community,” she says.

Still, Ludwig says, when it comes to comparing the lives of poor residents here to those living in other places: “I wouldn’t say that life is easier, especially for people who may be socially isolated, linguistically isolated, working multiple jobs, navigating transportation—individuals who may have to take three buses to get to work,” for example.

Ludwig worked in Pueblo’s health department before moving to Eagle County. She was struck by a huge cultural difference between the two places. In Pueblo, the government spending is much lower, and that’s evident in the services available to people. But there is also a greater, more public celebration of cultural diversity, Ludwig noted—more truly bi-cultural people who, though not immigrants themselves, speak and celebrate the language of their ancestors.

Maria Reyez works in the Garfield County Public Health office in Rifle, and lives in Battlement Mesa. She says she has seen how language can be a barrier for some of the new immigrants living in this area. There aren’t any English classes offered in town.

Reyez grew up as a native Spanish speaker in El Paso, Texas, and remembers it as a more integrated place than here. She’s not aware of any other Hispanic families living in her subdivision. Still, she gets along with all of her neighbors, and like Jasso, she likes the area’s tranquility and its natural beauty.

“I wish there were one name for both [Battlement Mesa and Parachute],” she says. “That’s the biggest issue with making people feel different. ‘I’m from Parachute. You’re from Battlement Mesa.’ If everyone just said Parachute, that’s going to make it easier.”

Ludwig notes that a limitation of Chetty’s study is that it doesn’t fully capture the lifespan of a transient low-income population like the one in much of the resort region: “Maybe we have a low mortality rate in Eagle County because people leave when they get to a certain age.”

There’s also evidence that geography affects people of different races in different ways, like this study showing that black Americans living in rural areas are at a significant disadvantage compared with both their white neighbors and urban blacks.

Asked if he’d rather live in a place where everyone is equally poor or where there are stark differences, Jasso answers, “I don’t agree with either one. I think people are people. They’re human. Everyone deserves to be treated equally.”