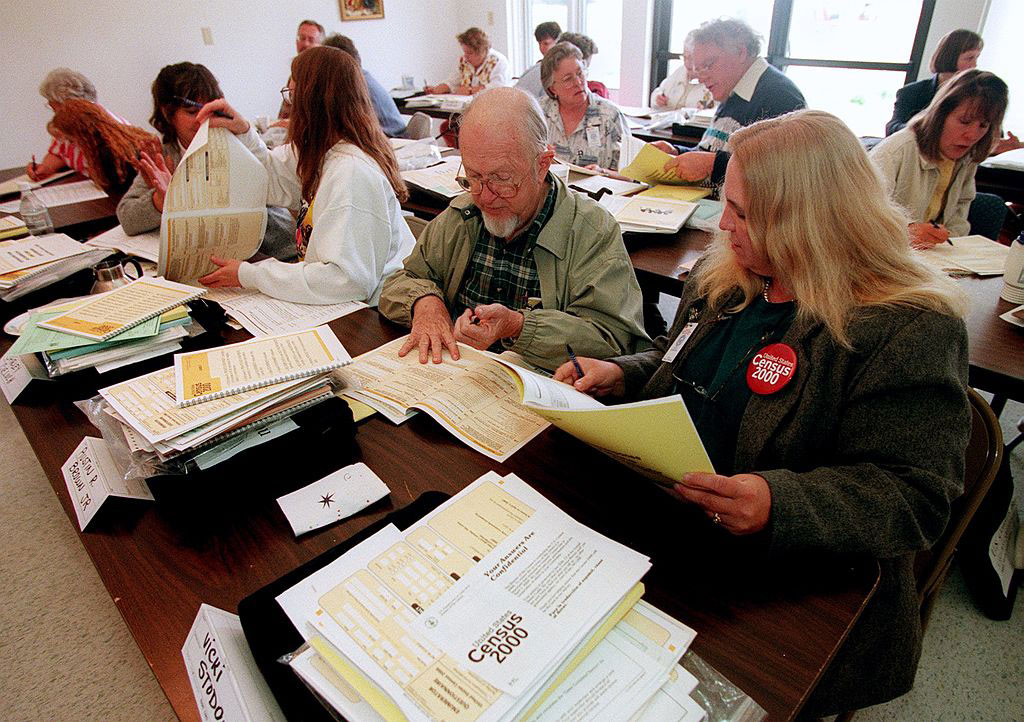

Census takers were trained at Risen Christ Lutheran Church in Arvada, Colo. before knocking on doors for the 2000 census. This year, outreach is at risk as concerns mount over the coronavirus. Photo by Glen Martin/The Denver Post via Getty Images

Census takers were trained at Risen Christ Lutheran Church in Arvada, Colo. before knocking on doors for the 2000 census. This year, outreach is at risk as concerns mount over the coronavirus. Photo by Glen Martin/The Denver Post via Getty Images

For advocacy groups pushing for a fair and full U.S. census count, the next 10 weeks are the playoffs, wedding day, opening night and launch window, all in one. The outcome of the coming weeks will have long-term consequences for the allocation of resources and political representation.

But with the coronavirus spreading rapidly throughout Colorado and the United States, multiple census outreach events have already been cancelled. Door-to-door visits, meant to start in May, are at risk. Colorado full-count organizers are calling the arrival of the virus and its cloud of real health worries a “disaster,” and a real challenge to long-term equity objectives.

“The timing could not have been more horrible for the census,” said Gillian Winbourn, project director for the nonprofit Together We Count in Denver. “It’s very disappointing.”

People who receive mailers from the U.S. Census Bureau beginning March 12 can respond immediately online or by phone. A federally organized effort to count people experiencing homelessness was meant to fan out from March 30 to April 1, among other events. Regional Census Bureau officials provided an online statement but did not respond to specific questions about coping with the coronavirus in their upcoming work.

The City and County of Denver—which, like many major cities, has spent its own money to boost the census count—had an entire menu of outreach plans and events that is now in jeopardy. One tactic was to put kiosks with tablet computers at all Denver Health community clinics, to catch large numbers of hard-to-reach residents who see clinics as a safe space.

“Gathering people at a clinic seemed like a great idea at the time, and that now sounds like the worst idea we ever had,” said Kaye Kavanagh, census coordinator in Denver’s Agency of Human Rights & Community Partnerships.

Indigenous people in metro Denver are dispersed across the region, and don’t have one neighborhood to saturate with census door-knockers or a radio station to use as a megaphone, said Rick Waters, co-executive director of the Denver Indian Center and a member of the Kiowa and Cherokee tribes. Outreach plans had long been focused on meet-and-greets and conversations at public events.

“American Indian people are social, and sometimes the sharing of information is best done face-to-face,” Waters said. Cancellation or low attendance at major events like the late-March Denver Pow Wow would be a big blow to the census efforts, he said.

Advocacy groups across Colorado used grants from nonprofit foundations and government agencies to plan for dozens of outreach events to coordinate with official census mailers going out March 12. The mailers encourage residents to go online to fill out their census form, call a phone number to talk to a census-taker, or return a form by regular mail. Later in the spring, census-takers hired by the federal government are to fan out through neighborhoods and hard-to-reach areas, from mobile home parks to smaller towns and reservations.

Cancellations are snowballing. Many groups, including those seeking counts of older Americans, had outreach planned at the popular 9News Health Fairs, which have now been postponed to August—after the census deadline. The Salute, the state’s largest senior expo, was postponed, and the Denver St. Patrick’s Day Parade was canceled, along with many other events. Outreach planners often organize to have trained census-takers with tablet and laptop computers at such events, to take counts on the spot.

On Tuesday, March 10 in Denver, Gov. Jared Polis declared a state of emergency to control the coronavirus spread, giving the state special powers to cancel large gatherings or take other public health measures that supersede local plans. As of the evening of March 11, the state was reporting 33 confirmed cases of the potentially deadly virus, with more test results of possible cases pending.

Advocacy groups traditionally spend years before the decennial April 1 launch date fighting for policy and practical changes that will expand the count of hard-to-reach groups, including the elderly, some racial and ethnic minority groups, rural residents and more. Latinx activists and community partners successfully battled to keep a new citizenship question off the proposed 2020 Census form, in a long and heated legal challenge.

Just two months ago, “we thought we had averted the disaster of the citizenship question, and we thought we had a fighting chance” at an accurate count, said Rosemary Rodriguez, executive director of Together We Count. Advocates had won another victory at the state level, Rodriguez said, in getting an official designation of elderly residents as hard to count, even though in the past they have voted and filled out the census in higher numbers than other groups.

Making the 2020 Census primarily an online experience may push it out of reach for more older Americans than in the past, the advocates have said, and state and nonprofit funding is needed to bring the technology to the elderly.

“We spent a lot of time trying to be creative about the census education process. Literally at the 11th hour, we find ourselves having to completely rethink the outreach we’ve been suggesting nonprofits engage in, to accommodate a health crisis,” Rodriguez said.

Things have happened so quickly, and change so much each day, that the advocacy community has not yet come up with a “helpful set of guidelines,” Winbourn said. “We are suggesting canceling some events and holding phone banks, depending on the type. We won’t be going around to homes until May 13, so we do have some time.”

Every decade, an entire subculture of nonprofit and local government partnerships spring up because the census results determine the makeup and the apportionment of Congress, huge portions of federal spending on health and social services, and countless business or government plans based on demographics.

A fuller count “makes a difference in political representation, local funding for our communities, planning by businesses, by federal and state and local governments. It makes a difference in all parts of our daily lives and most people don’t realize that,” Kavanagh said.

Racial disparities in undercounts and overcounts are acknowledged by the Census Bureau itself, Colorado writer Scott Downes noted in this space last fall. “As recent as the 2010 Census, 2.1% of Black Americans and 1.5% of Hispanics were not counted in the Census, meaning 1.5 million people of color were missed. … Similar rates of undercounting took place in 2000.”

Undercounts could cost Colorado tens of millions of dollars in Medicaid funding and support for safety net clinics each year, the Colorado Health Institute estimated in a 2019 Denver Post op-ed. Over the 10 years until the 2030 Census, losses would be close to $250 million.

With more public gatherings in Colorado being canceled or postponed every hour, the counting community is groping for new tools.

“We’ve been creative throughout this whole process, and now we’re going to have to get really creative,” Rodriguez said. “There’s a challenge, and we are eager to embrace it.”

So far, there is not much talk of extending the census beyond its return-by date of July. Denver’s Kavanagh said some focus will shift to traditional and social media campaigns that can reach people safely and remind them help is available online or by phone to complete the form.

It’s also important for organizers to remember, Kavanagh said, that people who have not responded to the March “launch” mailing will eventually be sent a full paper census form through the mail.

She worries most about recent immigrants who have been through years of targeted political attacks, and who are highly suspicious of most government contacts. Much effort, for example, was put into contacting Denver’s Spanish-only or Vietnamese-only speakers with personal outreach.

“Our outreach plans were to reach them where they gather,” Kavanagh said, “and they’re being told not to gather.”