To help cope with her grief after losing both a close friend and then her father to suicide two years ago, 16-year-old Karami Lyle began seeing therapist Steven Martinez at Central High School’s Warrior Wellness Center in Grand Junction. Lyle, who doesn’t drive, has also sought care at the school-based clinic for other health care needs, and said having access to such services at school is helpful for her mom’s schedule.

Yet at another high school nearby, other students won’t be gaining access to the same health care services as Lyle anytime soon.

A proposed school-based health center (SBHC) at the new Grand Junction High School campus was voted down 3-2 by the Mesa County Valley School District 51 Board of Education during its March 7 business meeting. Concerns regarding parental rights and a lawsuit against the health center’s proposed operator were two reasons cited by the board members voting against the clinic.

Clinic proponents—including some Central High students, who shared at school board meetings how they’ve benefited from having access to health care at school—were unable to convince the board’s conservative majority to proceed with plans to establish a school-based health center at Grand Junction High.

Central and Grand Junction high schools (l. to r.), which are a 15-minute drive apart. The new Grand Junction High School campus is being built adjacent to the current location, and is scheduled to be completed in 2024.

The Mesa County Valley School District 51 Board of Education has already received national coverage as a bellwether among school boards tacking to the right amidst larger “culture wars” playing out across the country. Stand For The Constitution, a Grand Junction-based conservative grassroots group, has become influential with the current iteration of the school board, according to those on both sides of the SBHC issue. This mirrors similar efforts and debates over things like school curricula and transgender student rights taking place in school board meetings nationwide.

While there’s no known national movement against SBHCs, some centers have gotten caught up in the “parental rights” discussions that are taking place across the nation, said Jeff Williams, director of communications for School-Based Health Alliance, a national SBHC advocacy organization.

Central High School’s SBHC opened in August 2020, as a collaboration between the school district and MarillacHealth, a nonprofit, federally qualified community health center providing care regardless of income or insurance status.

There are more than 2,500 SBHCs nationwide, with 70 such clinics located in Colorado that served 35,000 students last year. At SBHCs, students can receive wellness checks, sports exams, strep tests, treatment for chronic conditions such as diabetes, plus mental and sexual health care. Some school-based clinics, like the Warrior Wellness Center, also offer dental care.

In January 2019, an earlier iteration of the five-member school board had agreed to move forward with planning SBHCs for both Central and Grand Junction high schools. That changed after a notably partisan school board election in November 2020, when current School Board President Andrea Haitz, Vice President Will Jones and Treasurer Angela Lema were elected as a conservative bloc.

In March of this year, Haitz, Jones and Lema voted against the proposed school-based health center for Grand Junction High School, while fellow board members Doug Levinson and Kari Sholtes, PhD voted in favor. In citing their reasons for rejecting the school-based clinic, both Haitz and Jones mentioned a lawsuit against MarillacHealth filed at the end of 2022 by former employee Ana Noriega, alleging misuse of grant funds at the Warrior Wellness Center. (MarillacHealth CEO Kay Ramachandran told the Grand Junction Daily Sentinel that the case has “no merit,” and that the same “ex-employee filed a complaint with the Civil Rights Division against Marillac, which, after a thorough investigation decided in Marillac’s favor.”)

During school board meetings leading up to the vote, community members spoke both for and against opening a SBHC at Grand Junction High. Some who were opposed expressed concerns that students could receive medical treatment without their parents’ knowledge or consent.

Yet many such concerns are unfounded. In Grand Junction, parents must already register and sign paperwork at the beginning of the school year to allow their teens access to some of the health care available at the Central High School clinic, said Ramachandran. This includes diagnosis and treatment for things like common colds, strep throat and influenza. Parental consent forms are not required at the national level but are considered a best practice for SBHCs and are used widely, according to School-Based Health Alliance.

The entrance to the Warrior Wellness Center, the school-based health center at Central High School.

Colorado law does allow minors access to certain types of care without parental permission, including for mental health, addiction and substance use treatment, and reproductive health care such as birth control and testing for sexually transmitted diseases. Students may access those services wherever provided—not just at SBHCs—without notifying a parent, Ramachandran said.

“Having a health clinic at school ensures kids will access care when they need it,” Ramachandran said. “Not all kids can talk to parents about what’s going on with them.”

Federal law prohibits SBHCs from providing abortion care. To receive gender-affirming hormone replacement therapy, at a SBHC or elsewhere, at least one parent or legal guardian’s signature and consent is required, as well as a health care provider’s diagnosis of gender dysphoria, according to the Colorado Department of Human Services’ Youth Bill of Rights. Some clinics request consent from two parents or guardians.

At Central High’s SBHC, this is all moot: gender-affirming services are not offered there, said Rosa Gardner, a certified physician assistant at the clinic. And while there is no explicit legal prohibition against gender-transition surgery, Colorado school-based clinics don’t perform surgery of any type, said Aubrey Hill, executive director of Youth Healthcare Alliance.

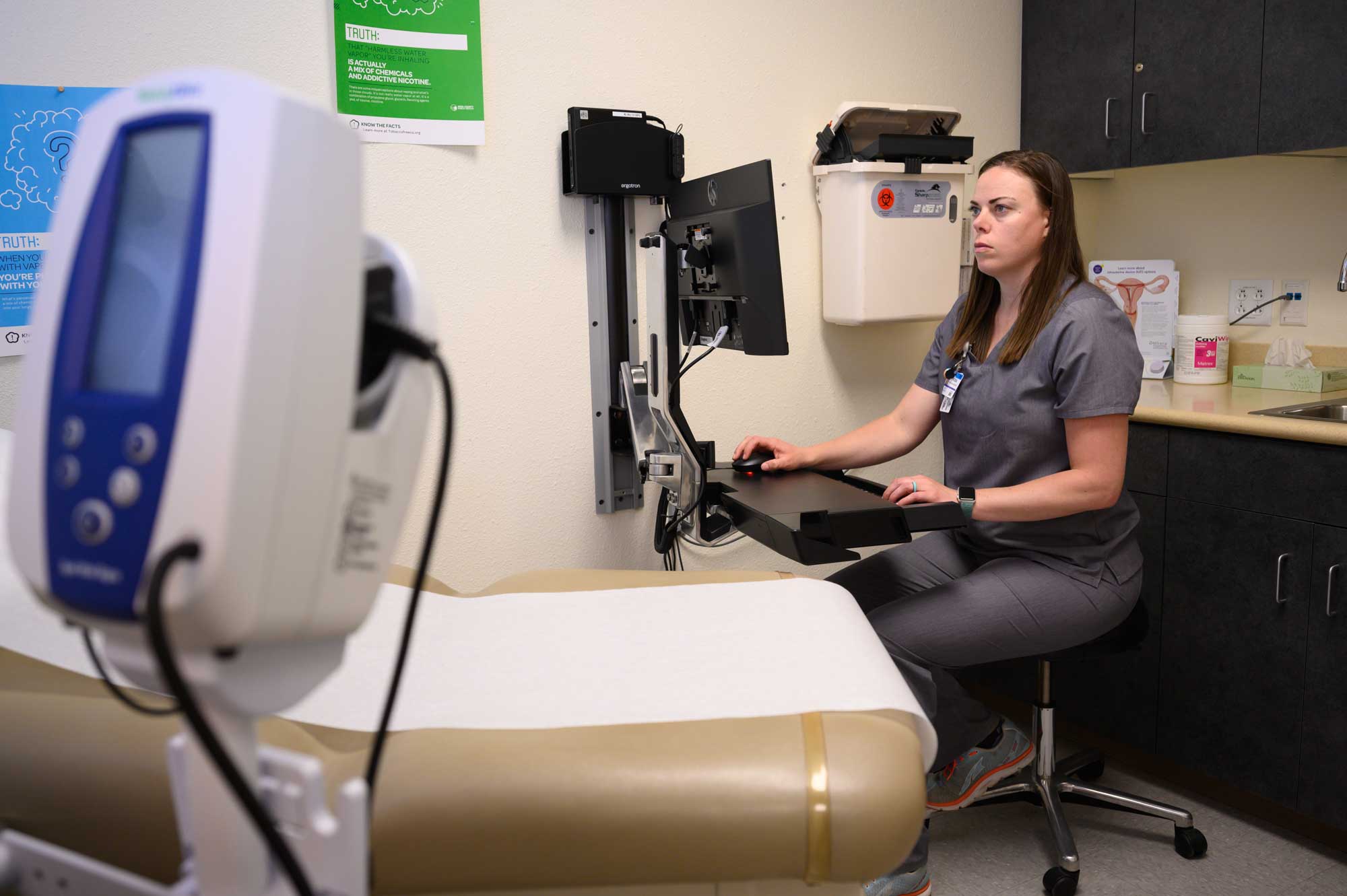

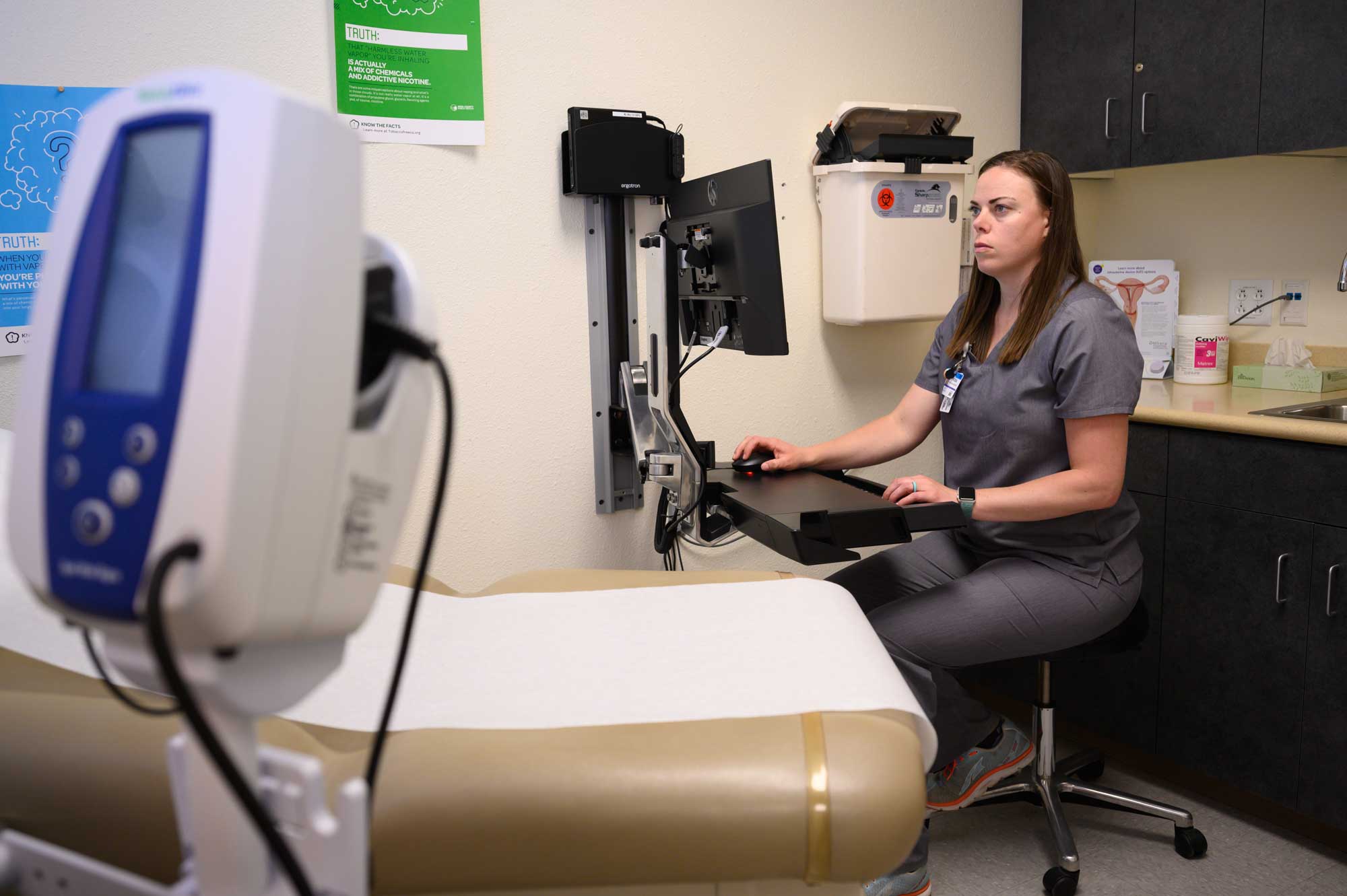

Certified Physician Assistant Rosa Gardner.

Members of Stand For The Constitution have regularly attended local school board meetings to voice opposition to SBHCs, and also shared their position on the group’s Facebook page, which has more than 2,200 followers as of April 2023. Ramachandran also recalled a parent at one school board meeting saying that opposition to the proposed Grand Junction High School clinic “began with school district mask mandates” during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In an interview, Tom Keenan, a Stand For The Constitution member and past president, said that “schools need to focus on educating and improving test scores and not get involved in health care.”

At the March 7 meeting, both Sholtes and Levinson asked how the district could approve a clinic for Central but not one for Grand Junction; both schools show similar rates of depression and suicide among its students. Sholtes said during the debate that there are studies that show a 30% reduction in suicide and depression where SBHCs exist.

“It feels political to me than belief-based or values-based,” Sholtes said during the debate, “and that feels really alarming to me.”

Levinson, a former school principal who also served on the pre-2020 iteration of the school board, told his colleagues before the vote that “For me, this is not a difficult decision, I’m focused on what’s best for kids. This, to me, is a no-brainer.”

Students testify for clinic

Lyle is one of several students who spoke before the board in favor of the SBHC at Grand Junction High. She said she feared that if the clinic was rejected, the school board would end up closing the Warrior Wellness Center at Central.

In an interview, Brooklynn Horton, 16, also expressed concern over the future of Central’s clinic. She said her primary care physician often dismisses her concerns and questions, whereas Gardner, the certified physician assistant at the Warrior Wellness Center, always takes the time to listen.

Brooklynn Horton.

“She cares about my health and personal life. I go in there every day to just talk to them,” Horton said of Gardner and her colleagues. “I stand in front, talk to whoever is working about my personal life.

“They genuinely care what’s going on,” she added. “They’ve helped me with my social anxiety. I have lot of friends that go to Grand Junction High School who would benefit—who have high anxiety, stress, but can’t leave school.”

Gardner treats common ailments like ear infections and sore throats, and also performs hundreds of sports physicals. If a student can’t afford the $20 copay or forgets to bring the money, MarillacHealth covers the cost of the visit, she said.

MarillacHealth receives funding from the State of Colorado, private donors and foundations. (The organization is a past grantee of The Colorado Trust, most recently in 2015.) It generates additional revenue by billing patients’ insurance, whether commercial or Medicaid. Patients without insurance may be charged a small copay but are not denied care if they can’t afford it. A hardship fund is available to help with copays.

Gardner at work at the Warrior Wellness Center.

Gardner said there are a lot of misconceptions surrounding school-based clinics, and that she is disappointed with the board’s vote against the new SBHC.

“Kids spend a lot of hours in the school building,” she said. “We have kids pop in and say ‘hi’ every day. We are trusted adults in their lives. To be able to talk to adults in a medical setting is a good skill. When they come in to schedule their own appointment, that’s a life skill. We’re absolutely not here to replace parents.”

To Gardner, the school board’s vote was about politics, not student well-being.

“Three members have taken the needs and direction of the community and set those aside for their own political agenda,” she said. “I feel frustrated on behalf of the students who spoke [in favor of the clinic]… it takes a lot of guts to speak up.”

Bryce Davis, a 17-year-old Central High School junior, also testified before the school board in favor of the Grand Junction High School clinic. Davis said in a later interview that he uses the Warrior Wellness Center for routine checkups and COVID-19 testing.

“Instead of having to leave school, I leave class and 20 minutes later I’m right back to class,” he said. “I have a primary care provider outside the school but the clinic here makes it a lot easier. With my primary care physician, I put off so much. My schedule is busy. My primary care doctor is always booked a month out. Here, at the school, I’m able to schedule the same week.”

Bryce Davis.

Mental health a “critical concern”

In 2018, the school district, MarillacHealth and various community partners convened an advisory committee to study the feasibility of opening SBHCs in the district. The committee contracted with the Colorado Association for School-Based Health Care (now known as the Youth Healthcare Alliance) to assess student needs and community resources.

“There was lots of support then. I do not recall objections,” Ramachandran said.

The resulting needs assessment focused on Central and Grand Junction high schools and their feeder middle schools. Mental health was found to be the most critical student health concern.

Students at both high schools reported feeling sad or helpless and having considered suicide more than their peers in the district and statewide. Students at both schools also reported drinking alcohol, and Central High students reported bullying, all at higher rates than their peers in the district and statewide. Many students interviewed for the needs assessment said their parents weren’t aware of these concerns, noting that adolescents can be reticent to talk about substance use and mental health.

The needs assessment additionally found that families enrolled in Medicaid experienced difficulty in scheduling timely appointments for sick children, or for mental health care. One out of three parents noted that cost and time constraints have caused them to delay or avoid health care for their children. One out of 10 cited lack of transportation as another barrier.

Horton, Lyle and Davis chat with Gardner (l.) at the Warrior Wellness Center.

In 2019, Mesa County Valley School District 51 was the first to volunteer in Colorado for a four-year research project conducted by Indiana University sociology professor Anna Mueller, PhD that seeks to provide schools with sustainable, actionable strategies for suicide prevention.

Mueller said she found school counselors in western Colorado to be “really overworked.” She cited one example where three students needed screening for suicide simultaneously, yet only two mental health staff were present. If there had been a SBHC at the school, the student could have been seen immediately by another health care professional, she noted.

“We worked it out, we were able to keep him safe,” Mueller said. “There’s a huge amount of need in these schools—not every day, but a lot of days.” She plans to return to Colorado in the fall to present her findings.

Mueller also cited lack of transportation as a significant barrier to accessing health care in Mesa County. She said she witnessed a situation where a school staff member had arranged for a free optical exam and glasses for a student who was unable to see his schoolwork. However, the student did not have transportation to receive the care.

“We have families struggling with transportation or getting time off work—having health care in schools really addresses that access problem,” Mueller said.

“Having health centers in schools is absolutely a brilliant solution to persistent health inequalities that we have in the U.S. health care system.”

A recall effort against Haitz was launched in early April. Haitz’s leadership has been criticized for multiple actions taken by the board, including its recent decision to close a high-performing middle school due to declining enrollment—while simultaneously preparing to open a new charter school, Ascent Classical Academy of Grand Junction, which is associated with the conservative Christian Hillsdale College in Michigan. Stand For The Constitution advertises the charter school on its Facebook page.

Haitz declined to be interviewed for this story. Lema and Jones did not respond to emails or phone calls seeking comment.

As for Lyle, the Central High student, she knows plenty of classmates who already or would benefit from a SBHC, especially for mental health care. She says she has friends whose family life is not so great, and knows teens who were trapped at home during the pandemic with abusive family members. She said a lot of her peers’ mental health has not recovered.

Plus, “We’re teenagers,” she said. “There may be some things we might not want to talk to our parents about, or we want a second opinion.”

Karami Lyle.