Aspen Miracle Center is on a quiet block in Westminster, Colo., in an unassuming building that looks like a giant, renovated home. Inside, pregnant people with substance use disorders are working toward sobriety in the weeks and months leading up to their deliveries.

They share rooms, cook meals together and participate in various classes and therapy geared toward helping them leave behind the drugs and alcohol they were using to start on a new sober path.

In the summer of 2017, Ashley Miller found her way to Aspen Miracle Center when she was about 6 months pregnant with twins. (Learn more in the first story in this series.)

“They made it like a home. It wasn’t like a treatment facility,” she said. It was her first time seeking treatment.

Aspen Miracle Center is situated on a quiet street in Westminster. Photo by Eli Imadali / Special to The Colorado Trust

Women who enter the program at the Aspen Miracle Center typically stay between 60 and 90 days, though some stay longer or return after their children are born. Aspen Miracle Center, run by Mile High Behavioral Health, is one of seven residential treatment programs in Colorado for Medicaid-eligible pregnant people, called Special Connections.

In Colorado, overdose is the second leading cause of death for pregnant and postpartum people. Advocates say more treatment options are needed to save pregnant people’s lives, and each of the seven facilities has limited capacity for pregnant people and their other children. Aspen Miracle Center has capacity for 16 adults and any children they have who are under the age of 2.

Aspen Miracle Center often has a waitlist because there are many people in need and because getting people admitted to the program has its barriers. Most patients accepted into the inpatient program are about seven months pregnant, though some reach out just weeks into pregnancy.

Every child that comes through the residential treatment program at Aspen Miracle Center with their parent gets to add their footprint stamps on the wall. Photo by Eli Imadali / Special to The Colorado Trust

“I think people find out they’re pregnant, they’re afraid, they know that their use is problematic, and they reach out for assistance,” said Rewa Bailey, program manager at Aspen Miracle Center. “However, the pull for that lifestyle is pretty heavy and doing something different and new is really scary. And so often, it’s months before you actually can get them in the door.”

Pregnant people often fear that health care providers will report them to child welfare agencies, leading to the removal of their children. (Learn more in the second story in this series.) If they overcome that fear and seek treatment, pregnant people may find that the services they need are fragmented and difficult to access.

In October 2022, the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy released a report detailing the cultural and systemic barriers pregnant people with a substance use disorder face. Among many examples, pregnant people with older children often have to arrange full-time child care to seek treatment. Housing stability may also be at risk. Many pregnant people are reluctant to leave behind their partners or other support systems to enter inpatient treatment.

Then there’s the issue of location. Of the seven Special Connections programs, six are on the Front Range, and the seventh is in Grand Junction—meaning that, even if there is space at a treatment facility, pregnant people in rural parts of the state may have to travel long distances to access one of the programs.

Bailey said the first step for many people entering Aspen Miracle Center is meeting their basic needs. That includes enrolling them in Health First Colorado (the state Medicaid plan) or other state or federal programs they’re eligible for, arranging care for other children they may have, and then either detoxing or enrolling in medication-assisted treatment, depending on what drug they were using.

Rewa Bailey, the program manager at Aspen Miracle Center, in front of the facility on April 5, 2024. Photo by Eli Imadali / Special to The Colorado Trust

For pregnant patients with an opioid use disorder, medication-assisted treatment is considered the standard of care by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Buprenorphine or methadone are used to avoid withdrawal and possible pregnancy complications such as preterm labor, fetal distress or miscarriage. The medications are partnered with behavioral therapy and other services.

For people who do not want or can’t access inpatient services, there are medication-assisted treatment clinics throughout the state—but, as detailed in the White House report, pregnant people are less likely to receive treatment. In a randomized field experiment, people posing as pregnant women with a substance use disorder were 17% less likely to be accepted for medication-assisted treatment appointments by outpatient clinics compared to identical non-pregnant women. Pregnant people of color, those who live in a rural community and non-English speaking people were also less likely to receive medication-assisted treatment in pregnancy.

When Miller first got to Aspen Miracle Center, she had already detoxed from methamphetamine, which does not typically require medical detox or medication-assisted treatment. She participated in group and individualized therapy classes and worked with a case manager.

The goal at Aspen Miracle Center is for every family to be connected to ongoing behavioral health resources after 60-90 days of treatment. Then, Bailey and her team work to help program graduates secure stable housing.

“It’s pretty rare that ladies come in that have housing already. Most of our ladies are unhoused, couch surfing, living with family, whatever,” Bailey said. “We try to work with them to find a safer option than where they came from.”

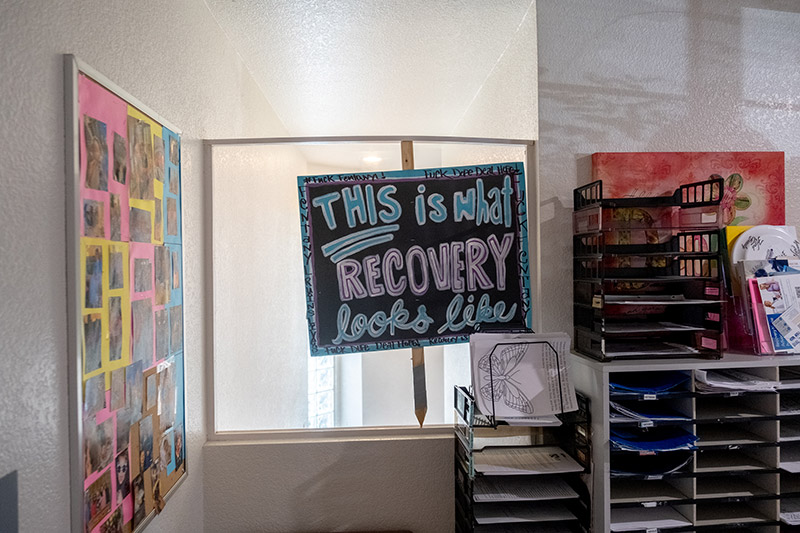

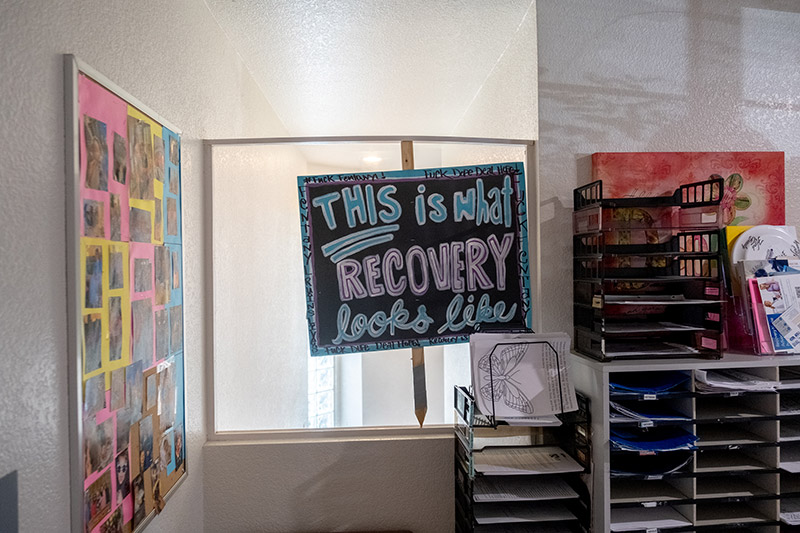

A motivational poster inside Aspen Miracle Center. Photo by Eli Imadali / Special to The Colorado Trust

Housing is also an essential component of maintaining custody of children after delivery. For Jaid Redmon-Greene, who was unhoused during her pregnancy with her first son in 2021, finding stable housing was required by her child welfare social worker to get him back from foster care and to ensure she would maintain custody of her second child.

After months of living in a hotel, she got a Section 8 housing voucher and moved into her apartment in April 2023.

“This is a really nice space. I chose here because it has that security gate in front where I felt really secure,” said Redmon-Greene, who spent time at Aspen Miracle Center and New Directions for Families, a treatment center operated by Valley Hope. “There’s no one walking from the streets in here. It’s nice.”

Miller tried several treatment centers before Aspen Miracle Center. One was New Directions for Families, and another was The Haven, but Miller didn’t like the treatment program. She went to Arapahoe House, which was the state’s largest alcohol and drug treatment provider at the time, but she was only there for about a month before the facility abruptly shut down in 2018.

Successful treatment the first time around is elusive for many. “The timeframes of these systems don’t align well for early recovery. This is a chronic relapsing brain disease that doesn’t just go away immediately,” Bailey said. “If you are coming from a state of being unhoused and don’t have resources and don’t have support, and don’t have family, and don’t have a safe place to go and are expected to get sober, stable, and safely housed in 12 months—that’s a lot.”

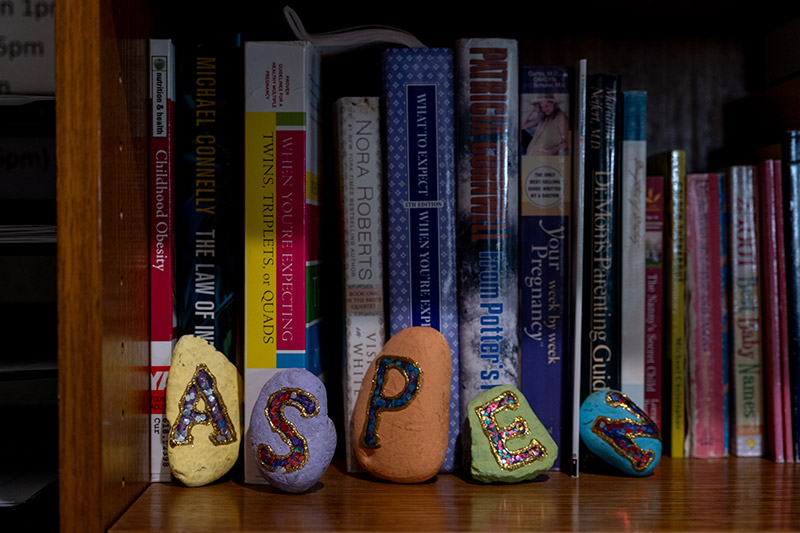

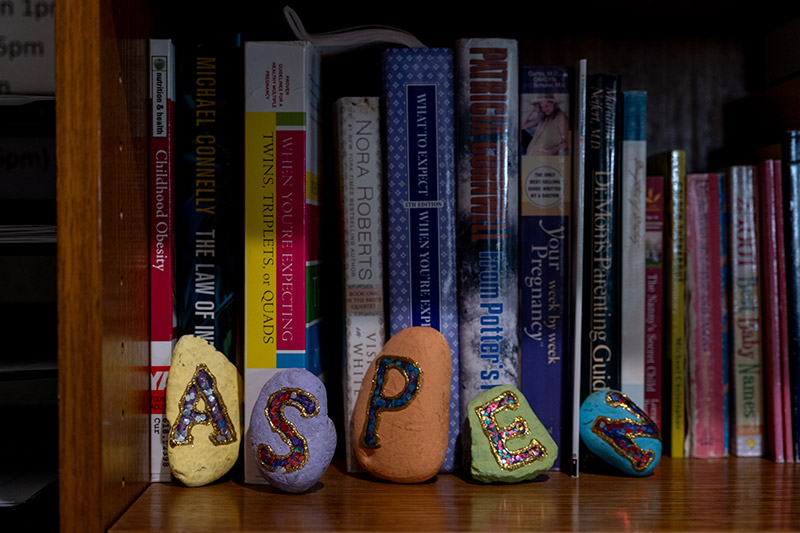

Painted rocks spell “Aspen” on a shelf at Aspen Miracle Center that is lined with books on pregnancy and parenting. Photo by Eli Imadali / Special to The Colorado Trust

Miller spent the next 9 months at Aspen Miracle Center with her twins before she finally had to leave so that other people could take her place. She secured a spot at Joshua Station, a two-year residential program for families with children. There, Miller was able to obtain her undergraduate degree, work and take care of her twins.

“Aspen Center prepared me for independence. Joshua Station gave me that independence, or at least it fostered it,” she said. “Now, I’m here today, able to be totally independent.”

Bailey works with clients to find transitional housing like Joshua Station or more permanent options. Still, she said it’s one of the most challenging steps for discharging patients from Aspen Miracle Center. Only a few of those transitional housing programs take children, and many of the programs are affiliated with religious organizations, which, for some people, isn’t a good fit.

Today, Miller is working toward buying a house through a Habitat for Humanity program. She finished her undergraduate degree and earned a master’s degree in clinical behavioral health care with an emphasis on addiction counseling. She works with the Colorado Office of Respondent Parents’ Counsel as an independent contractor. She created her own LLC, Generational Healing, as a parent advocate supporting families navigating the child welfare system.

“I get to know them, and many of my clients will describe me as a friend because I show up for them, and I’m a safe person for them, and I get to do that for them,” Miller said. “I love my clients.”

She sees parallels between her experience and that of her clients. She doesn’t think that removing children from their families is helpful in most cases. Instead, it breeds trauma that becomes generational.

“They grew up in the system, or they grew up with parents that did substances, or they grew up with violence in the home,” she said, “and then they do it again because that’s what they know.”

Bailey said the first step for many pregnant people entering Aspen Miracle Center is meeting their basic needs, such as drug detox, Medicaid enrollment and arranging child care for other children. Photo by Eli Imadali / Special to The Colorado Trust

Part 1 in series: As Opioid Epidemic Worsens in Colorado, Pregnant and Postpartum People Are Dying

Part 2 in series: Colorado Changed its Definition of Child Abuse and Introduced “Plans of Safe Care.” The Impact isn’t Clear.