Jose and Junita Martinez stand next to the part of the communal irrigation system that flows through their property in Costilla County, in Colorado’s San Luis Valley. Photos by

Luna Anna Archey

Jose and Junita Martinez stand next to the part of the communal irrigation system that flows through their property in Costilla County, in Colorado’s San Luis Valley. Photos by

Luna Anna Archey

Every summer in Colorado’s San Luis Valley, a long, high desert valley ringed by mountains, Jose Martinez watches in admiration as water flows from an irrigation pipe across the contours of his land, feeding the eight acres of alfalfa he grows near his home in San Francisco, a town of less than 90 people. The water comes from a network of communal irrigation ditches, or acequias, which comes from an Arabic word meaning “water bearer.” The acequias were built in part by his ancestors who arrived in southern Colorado more than 150 years ago with other Hispanic families from what is now New Mexico, establishing seven villages around Culebra Creek.

“I get to thinking, back in the day, these men dug it all by what we call pico y pala—pick axe and shovel,” Martinez, 76, told me when I visited recently. We were sitting in his kitchen on a cold October day with his wife, Junita, 70, while the two of them explained how acequias work.

Unlike normal irrigation ditches, acequias are a communal resource, collectively owned and governed by their parciantes, or members—the group of small-scale farmers with water rights to the ditch. Acequias are egalitarian, too: whether you irrigate one acre or 100 acres, you get one vote in decisions about the ditch in exchange for helping to clean and maintain the acequia. The parciantes elect a three-member commission to make decisions around ditch maintenance and operations, as well as a mayordomo to manage the irrigation infrastructure and tell people when they can irrigate and when they have to shut their gates.

In Colorado, acequias are found in four of the southernmost counties and irrigate only a tiny fraction of the state’s agricultural output. But in a region where some water rights have been sold to the highest bidder and private gain is sometimes prioritized over collective well-being, acequias remain a powerful antidote to the forces threatening rural communities—a way of valuing local resources beyond their dollar amount and a catalyst for sharing them in times of scarcity. During dry years, acequias work to ensure that everyone weathers the shortages equitably; occasionally, Jose has opted to forego his water entirely when he sees no prospect of a decent crop, so that other parciantes can have more.

“Our concept is community,” Junita explains. “If I can’t get something, why should I hurt my neighbor, if I could just let him have my water—maybe he can grow something?”

The Culebra-Sanchez Canal, a feeder ditch in the acequia system in the San Luis Valley.

* * *

That communal mindset originates in part from the families who arrived in the southern San Luis Valley in the mid 19th century to settle the one-million-acre Sangre de Cristo Land Grant. Drawn by promises of land and resources, they established small farming communities on land where the Cuputa band of Ute people had roamed for thousands of years, until they were gradually killed or forced out by European colonizers beginning in the 1600s. The families settling the valley beginning in the 1850s were primarily from Mexico, which had sold the territory now known as New Mexico—including the southern end of the San Luis Valley—to the U.S. government a few years earlier at the conclusion of the Mexican-American War.

Families built acequias and shared access to a mountainous tract of land in the nearby Sangre de Cristo mountains, known locally as La Sierra, which they relied on for water, firewood and foraging. The land grant was eventually sold, but its subsequent owners honored the historical rights of local families to access La Sierra.

Growing up, Jose Martinez remembers how families built cellars to store the vegetables grown on the land nourished by the acequias, as well as meat from deer and elk hunted in La Sierra—food that would last them the winter. Although they live in what is now one of Colorado’s most impoverished counties, “we ate like kings,” he said.

That all changed in 1960, when John Taylor, a North Carolina timber baron, bought 77,500 acres of La Sierra, renaming it the Cielo Vista Ranch and closing it off to the local community to create a logging operation. Taylor’s logging wrought lasting damage on the land. Poorly constructed roads created erosion, reducing the amount of water that flowed from the mountains into the acequias, according to area residents.

The water wasn’t the only resource reduced or eliminated as a result of Taylor’s actions. Without access to La Sierra for grazing, local families lost their herds and the culture of self-sufficiency that had sustained them for decades. Many, like Jose Martinez’s family, moved out of the valley. Those that stayed saw their health and well-being deteriorate. People went on food stamps and rates of diabetes soared. There were psychological impacts, too.

“You lose the relevance of what your land means,” said Shirley Romero Otero, the head of the Land Rights Council, which formed in the town of San Luis in the late 1970s to stop Taylor from denying access to the property. (A group of San Luis community members are participating in The Colorado Trust’s Community Partnerships strategy; Romero Otero previously was part of this effort.)

In 1981, the Land Rights Council mobilized local residents to sue Taylor for blocking their historical right to access the property. The ensuing legal battle lasted 40 years, fought by generations of the same families and leading to an April 2003 Colorado Supreme Court ruling, Lobato v. Taylor. The ruling granted people the right to graze their animals, cut timber and gather firewood on the land, if they could prove they were heirs to property that was part of the original Sangre de Cristo land grant.

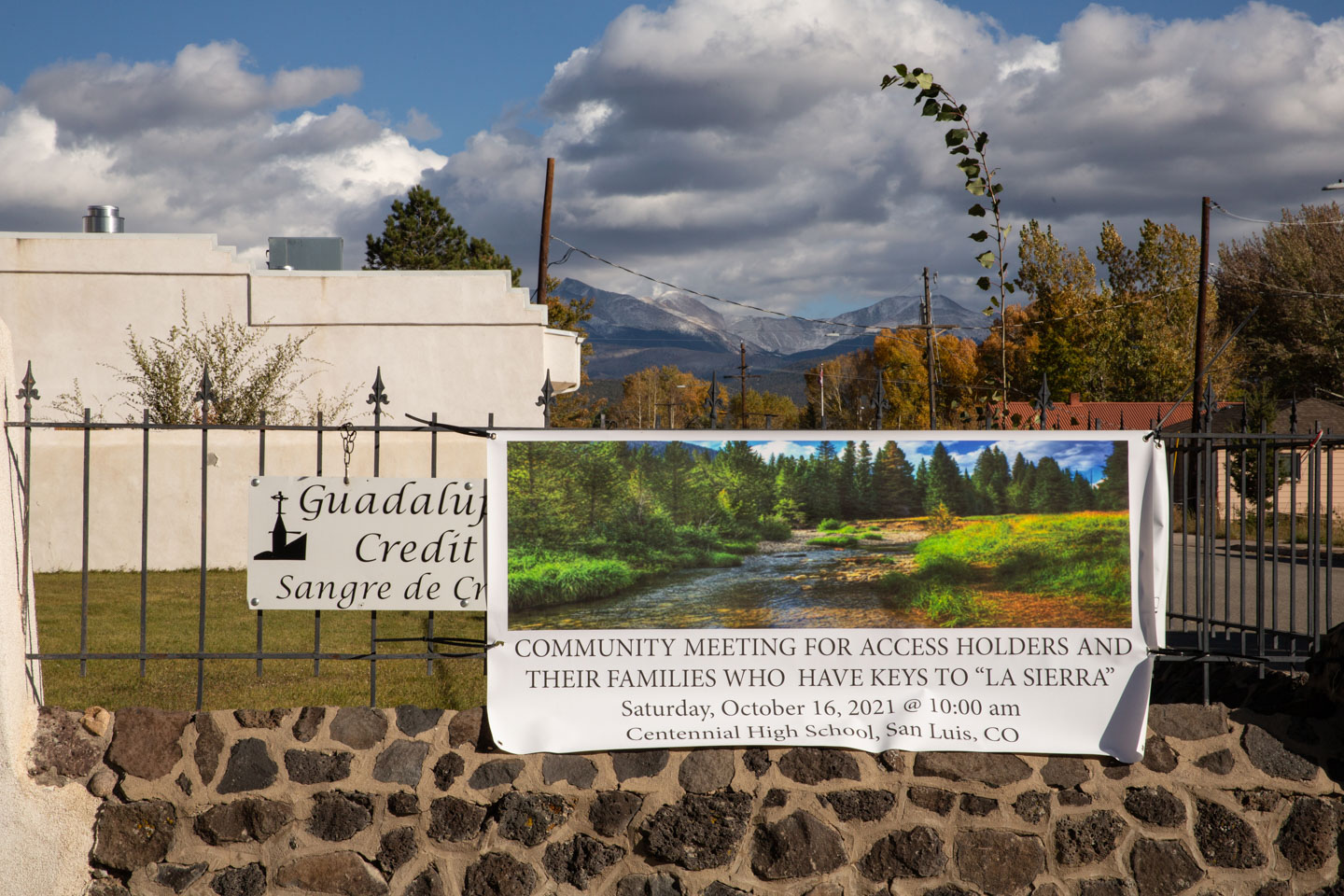

A sign in the town of San Luis provides notification of a community meeting about accessing La Sierra.

* * *

“We’re such diehards,” Junita told me, pointing to an old black-and-white photo from the early days of the land rights struggle taped to their refrigerator. Her husband was among the roughly 5,000 people given keys to access the ranch gates after a nearly 15-year process of identifying the land grant descendants.

“We won’t let go,” Jose added.

The Martinezes owe their persistence in part to the acequias, which are the lifeblood of each village, binding people to the land and to each other. Every spring, acequia communities gather for an annual ritual called La Limpieza to clean the ditch in preparation for the irrigation season. For families, it serves as a de facto reunion—regardless if someone has moved to Denver or to California, people come back for La Limpieza.

For Junita, that communal aspect is why acequias are important: working together to cultivate a shared resource. It’s also why she feels so strongly about protecting those resources from wealthy outsiders who threaten that culture. “We’re a land- and water-based people,” Junita explained.

The current owner of the Cielo Vista Ranch is William Harrison, heir to a Texas oil fortune, who bought the Cielo Vista property in 2018. According to its real estate listing, the ranch was listed at $105 million and encompasses 23 miles of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, including 18 peaks over 13,000 feet and one over 14,000 feet, Culebra Peak—the highest privately owned mountain in the U.S., and quite possibly the world.

Harrison’s ranch hands have intimidated and harassed local people who tried to access the property, according to court filings and residents—despite the legal rulings affirming the rights of the land grant heirs. With the threat of a violent confrontation growing, Jose and Junita’s children told their father they don’t want him going up onto the ranch alone to collect firewood, which he, like many locals, uses to heat their home.

A week before I visited, the Land Rights Council filed a motion in Alamosa Municipal Court to safeguard local residents’ rights to access the ranch. During a two-day hearing, a judge heard testimony about how the ranch’s aggressive surveillance tactics infringed on the community’s hard-won traditional land rights, including tracking people with drones and armed ranch hands approaching people with dogs. The ranch denied use of such tactics.

In an email, Harrison, through his lawyer, wrote that he believes that a few “bad apples” have abused those rights on occasion, illegally hunting, joy-riding ATVs and sneaking onto the property to fish. “That being said, we are fully committed to bringing the animosity of the past to a close, and are making a good-faith effort to bring healing and peace,” he added.

A fence, and a sign warning against trespassing, marks a boundary of the Cielo Vista Ranch in Costilla County.

* * *

If acequias are the seams holding communities together, they are also what makes them vulnerable: the stitching that can come undone. In recent years, developers have approached communities elsewhere in the San Luis Valley to buy their water rights and then move the water from the aquifer below the valley over Poncha Pass and into the Arkansas River for growing Front Range cities.

“Some of those places look like ghost towns because of that,” said Peter Nichols, a lawyer with the Acequia Project, a pro-bono legal assistance program supported by the University of Colorado Boulder Law School.

Thus far, acequia communities have resisted those efforts, ensuring their water stays with the land. With the help of the Acequia Project and Colorado Open Lands, an environmental nonprofit, acequias have adopted bylaws that protect acequias from outside buyers.

Still, like any collaboration, acequias are not perfect, said Sarah Parmar, the director of conservation at Colorado Open Lands. “It’s messy because there are human relationships involved, and anytime you have a community that goes back multiple generations, there are going to be grudges and things that have happened that they’re going to bring into those situations,” Parmar said.

But more than anything, acequia communities recognize that water is not just an asset; “it’s a piece of everything,” Parmar told me. “If you pull on that thread, the whole sweater unravels.”

* * *

Jose grabbed Junita’s arm to steady her as the two walked outside to show me the Nana Ditch, the “mother ditch” that gurgles beneath the willow trees in their backyard.

“It would kill me to see water flow by that doesn’t belong to us,” Junita said. “We’d have to go away.”

Today, abandoned houses are scattered amongst the roads and villages of the Culebra watershed—a reminder of how this community, like so many rural communities, has changed. North of the villages, giant agricultural operations have replaced the smaller family-run vegetable farms that once filled the San Luis Valley, while their high-tech center pivot irrigation systems are depleting the aquifers beneath the valley floor at an alarming rate.

Meanwhile, so many people have left, with the population of Costilla County nearly half what it was in 1950. When their children were growing up, Jose and Junita moved to Colorado Springs so the girls could get a better education. But people are returning to the valley, too, like Martinezes did in 2002. Jose began growing alfalfa on his family’s eight acres again, and a few years ago, two of the girls bought the lots on either side of their parents, where they hope to one day build their own homes.

In the Spanish dialect spoken in northern New Mexico and southern Colorado, there is a term called querencia, which translates roughly to “heart home or place.” Even after they left the valley, Jose and Junita would bring the girls back to San Francisco every summer to remind them: “This is where you come home.”