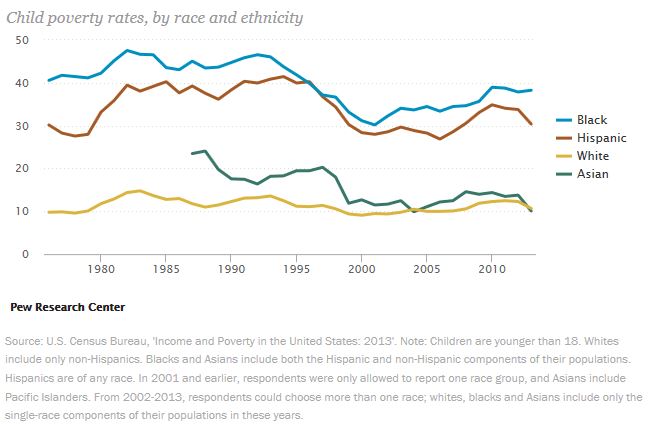

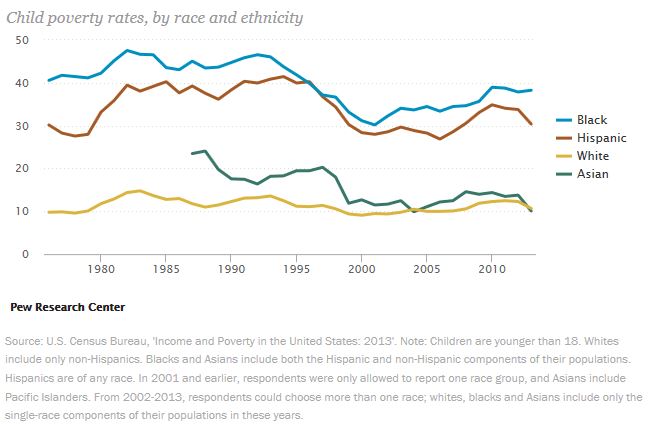

Nationwide, child poverty has declined since the end of the recession. But one group of kids hasn’t benefited from the economic recovery, according to new research by Pew Research Center (above image: top chart at link).

Around 38 percent of black kids in the U.S. lived in poverty in 2013—a rate that held steady since 2010. That’s almost four times the rate of poverty for white or Asian children.

Does Colorado match the national picture? Yes and no.

Like those around the country, black kids in Colorado are much more likely than their peers to be living in poverty, according to data compiled by the Colorado Children’s Campaign. Around 33 percent of African-American children in the state were poor in 2013, the latest year for which data are available. White kids in Colorado—like their peers nationwide—are nearly four times less likely than black kids to be poor.

Chaer Robert is with the Colorado Center on Law & Policy, an anti-poverty research and advocacy group. She notes that African Americans in Colorado and around the country face a litany of obstacles to escaping poverty and gaining wealth, including racial discrimination in hiring, a higher rate of single parenthood and lack of access to well-funded schools.

But Sarah Hughes, research director at the Colorado Children’s Campaign, notes that the overall trends for child poverty look a little different in Colorado than nationwide. In fact, they’re nearly reversed.

Unlike in the rest of the U.S., Colorado kids haven’t seen an overall decline in poverty rates since 2010, Hughes notes. Statewide child poverty rates have remained at around 17 percent, according to Census data, lower than the 2013 national average of 20 percent.

Among black children, there was actually a small decrease in the poverty rate since 2010, when it was around 39 percent. But Hughes says it’s not enough to be statistically significant.

“It’s a little harder to draw conclusions about Colorado’s African-American child population,” says Hughes, “because that population is so small that [the African-American child poverty rate] jumps around from year to year.”

There was a large—and statistically significant—drop in black child poverty from 2012 to 2013, Hughes notes, from 41 percent to 33 percent, or 8,000 fewer kids living in poverty. But it’s not clear what caused it.

“I’ve been trying to rack my brain and think about why that may be,” says Hughes. It could be that overall, the Colorado economy is stronger than the rest of the country—especially in Denver, where the state’s African-American population is concentrated. Or it could be an anomaly that won’t be borne out by future data.

Robert advocates for policies like raising the minimum wage, improving access to affordable child care and lowering barriers to employment for those with criminal records as ways of lifting black children out of poverty.

“Hopefully,” says Hughes, “we’ll continue to see the African-American population here being able to take advantage of the economic recovery.”