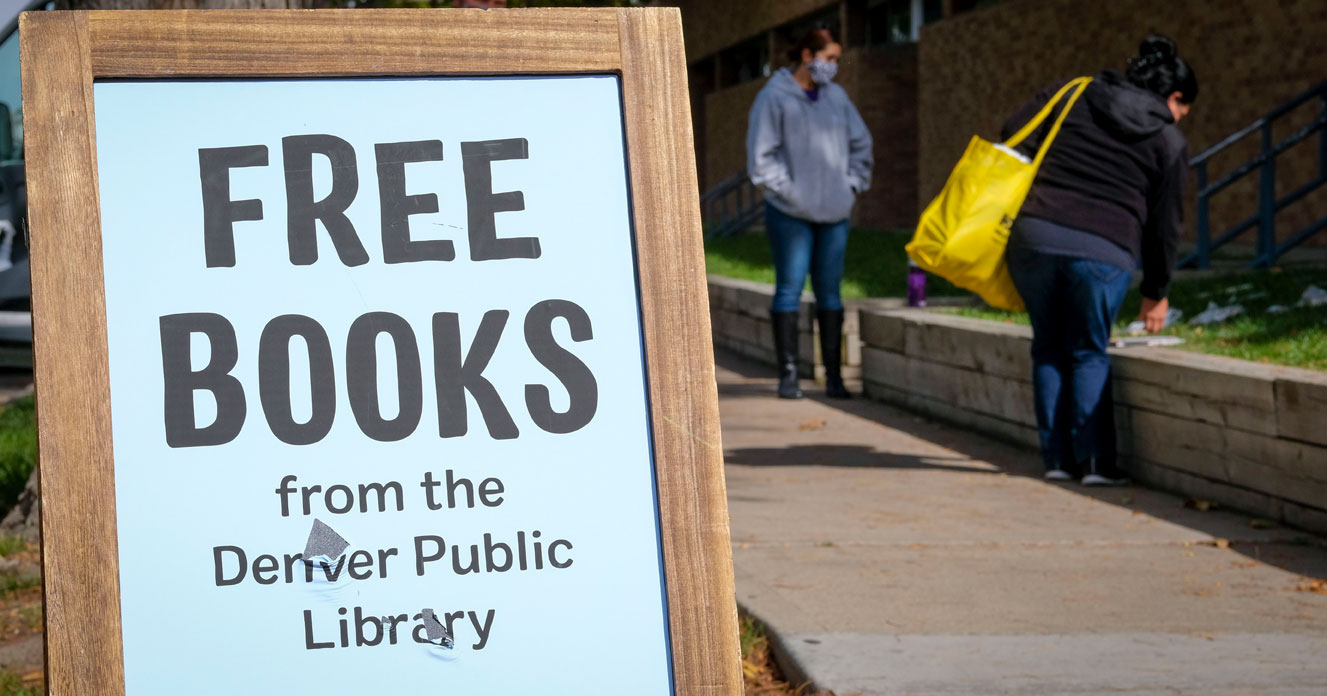

Denver Public Library distributed free books at Swansea Elementary School on Thursday, Oct. 15. Photos by Joe Mahoney / Special to The Colorado Trust

Denver Public Library distributed free books at Swansea Elementary School on Thursday, Oct. 15. Photos by Joe Mahoney / Special to The Colorado Trust

On an unusually hot October day, families in the northeast Montbello neighborhood of Denver picked up free lunches at the elementary school—and free books from the Denver Public Library’s bookmobile.

Joy Brown was choosing books for her family. “We used to go to the library all the time,” said Brown. Since the pandemic, she has not been comfortable going because her 7-year-old son has asthma. (Denver Public Library recently postponed plans to reopen in-person services, due to rising rates of COVID-19 in the city.)

Brown said she struggles to know the types of books her children should be reading. Before the pandemic, teachers would recommend books by grade level, and she misses that expertise.

April Duran and her daughter Novahlee, 3, chose The Koala Who Could by Rachel Bright from the picture books available for checkout from the bookmobile. Novahlee, wearing a Disney princess gown, also got a free blue backpack, craft bag and new books. “I really like the bookmobile because it is free,” added April Duran.

“She loves for us to read to her,” she said. “Especially during the pandemic, it keeps you occupied.” They read books in English and in Spanish, and they also speak Spanish at home.

Reading books with young children stimulates brain development, encouraging language and early literacy skills, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics. It can strengthen social and emotional bonds between children and parents, too. Having books in the home is associated with children’s success in school, and those benefits extend into adulthood, according to a recent study.

“We know that having books in the home is a strong indicator of success in school. And we know for some kids that isn’t an option because families are living in poverty or have toxic stress,” said Melissa Hisel, director of Lafayette Public Library.

“The stress levels for families have definitely increased,” said Deana Hunt, senior vice president of community impact for Pikes Peak United Way in Colorado Springs. The United Way chapter helps register families for an international literacy program called Dolly Parton’s Imagination Library. Job loss, food insecurity, and difficulty paying rent stress families who may have already been in crisis before the pandemic, said Hunt.

A recent poll by the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health found that a majority of families said they had serious problems caring for children during the pandemic, and one in three said they had serious problems keeping their children’s education going.

“As we’re trying to look at priorities, we just want to make sure that children have access to books, as well as food,” said Hunt.

Getting books into homes

With Imagination Library, children receive a book in the mail each month through their 5th birthday. Since its inception, 13,000 children have graduated from the program and 440,235 books have been sent to homes in El Paso and Teller counties.

Receiving a new book in the mail might spark a moment to decompress as a family and read together, hopes Hunt. She has noticed an uptick in Imagination Library registration since the pandemic.

“Families are busy, especially lower-income families where both parents work multiple jobs,” said Hunt, adding that families may not have time to visit the library.

Denver Public Library’s bookmobiles were out on the street last April after the stay-at-home orders were lifted, said Olivia Gallegos, communications manager for the library. Librarians organize and bundle donated books by grade level for kids at Denver Public Schools’ free meal sites.

Denver Public Library’s Olivia Gallegos, right, hands books to Library Program Associate Joshua Royal as they pick up books after the bookmobile’s visit to Swansea Elementary School.

“Kids can come by, pick up their meal, and get some reading material,” said Gallegos, adding that bookmobiles are also at Denver Housing Authority sites, older adult communities and recreation centers.

Yvette Rios of Denver, who was also at the bookmobile with her 11-year old daughter Neila and their chihuahua, said they didn’t read any books over the summer. “It was too hard because I was working,” said Rios.

Neila, who attended John H. Amesse Elementary, where the bookmobile is parked, had outgrown many of her books at home. She brought home The School is Alive by Jack Chabert.

At many Denver libraries, you can now place holds and get curbside pickup of specific books, as well as request grab bags of books by reading level or your child’s interests. Gallegos said it’s challenging that some families may not know about these library services. “That is the access gap we’re seeing now,” she said.

Hisel worries that Lafayette families, especially in underserved communities, do not have books at home. The Lafayette Public Library remains closed to visitors after the pandemic and a July ransomware attack on the city’s IT infrastructure.

The library’s closure put the summer reading program in jeopardy. So Hisel and her colleagues hopped on bikes and stuffed Little Free Libraries with books in English and Spanish (Hisel said 18% of families in Lafayette speak Spanish at home). The library also gives out books at Sanchez Elementary at Boulder Valley School District’s weekly free-meal site.

Helping bridge the digital divide

Some Lafayette homes do not have internet, putting additional strain on families learning online or trying to read books online. “One of the things that we knew was an issue is the digital divide and people’s access to digital literacy. That has really been amplified since the pandemic,” Hisel said.

With the library doors still closed, the parking lot is a de-facto hotspot. Students as young as elementary school age come and log on to free Wi-Fi outside the library. Hisel said the library is intentional about leaving the Wi-Fi on 24-7 (power outlets are also left open and unlocked).

All Denver Public Library branches also leave their Wi-Fi on 24-7, seven days a week. “The pandemic has been hard on everybody, but especially parents of school-aged children who have moved to virtual learning,” said Gallegos. “The digital divide is real.”

Colleen Gray, executive director of The Literacy Project in Eagle County, echoes those concerns. The Literacy Project provides English-language tutoring to adults and children in cities like Avon, Eagle and Gypsum. Tutoring was in person before the pandemic, but is now largely online. Gray said many of their adult learners do not own a computer, or must share a computer with their children, making online tutoring a challenge.

The Literacy Project fundraised to buy 15 Chromebooks for its adult learners. Gray said their programs have been busy as parents amp up literacy and computer skills to support their children online. Meanwhile, volunteer tutors with The Literacy Project have embraced Zoom and Google Hangouts to connect with their middle school students online.

Back in Denver, librarians repurposed laptops that patrons could normally check out from branches to create 12 outdoor, pop-up laptop spots. Anyone can walk up and use a Wi-Fi-connected laptop for up to 30 minutes—no library card required. Librarians clean laptops after each session.

Gallegos said the library’s virtual storytimes, which are bilingual and posted weekday mornings, have been very popular. Its phone-a-story program (720-865-8500) lets kids call in and hear a story in multiple languages.

Missing books and missing community

In-person storytimes are still on hold for many libraries, including the Crowley County School District and Combined Community Library in the southeast Colorado town of Ordway. Its director Jody O’Leary said they weren’t comfortable holding monthly in-person storytime because most of the adults who came with children are grandparents and at-risk individuals.

Lafayette Public Library’s Hisel said that storytimes in the library are a touchstone of early development and literacy, when very young children socialize with other children and community members, touch books and explore the library. One such program, aimed specifically at infants, had brought in upwards of 50 people per week before the pandemic.

It is difficult to duplicate that community virtually, said Hisel: “Those babies have grown and we’ve missed them.”

Book bags for preschoolers in Eagle County are mostly on hold, said Gray. Normally, The Literacy Project circulates 600 bags (each with four books inside) to area preschoolers to take home, read with their parents, and bring back in exchange for another bag. The Literacy Project will take new steps to quarantine and wash books and bags when preschools are ready to restart the program.

Libraries take similar steps to quarantine and wash books before putting them back into circulation. And Hisel said that care for books and people is part of the complex role that public libraries play today: “It’s important to think about the resilient role that libraries play in a community in sustaining and rebuilding after big disasters happen.”